January 7, 2016 – Is dark matter a Universe in parallel with the one we can see? Does dark matter have an equivalent periodic table?

These are questions I have been contemplating for the last few days after reading about the additional four new elements added to the periodic table of visible matter. Just in case you missed it the new elements are human-engineered and super heavy. They also exist in time frames measured in fractions of a second. Their temporary names:

- ununtrium

- ununpentium

- ununseptium

- ununoctium

I’m surprised no one picked unobtainium, the name of the ore being mined on Pandora in the movie Avatar. But that may still happen because naming human-created elements follows a set of unusual rules. You can name them after figures in mythology, after places, countries, specific properties or the names of scientists who discover them. These heavy elements are created by scientists when they smash lighter elements together and analyze the fallout. If the merged atom lasts for a few microseconds, voila, you have a new member for the periodic table which now stands at 118.

Why do we do this? Because scientists, like the happy one pictured below, one who discovered one of the new elements, keep searching for heavier atoms in pursuit of a theoretical stable of super-sized elements forming visible matter.

But what about the matter we cannot see….dark matter? I just finished reading Lisa Randall’s book, Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs. Randall is an expert in theoretical particle physics and a cosmologist. In her book she describes how dark matter dominates the Universe making up more than 80% of all matter. This is matter invisible to us yet we know it exists while not knowing its specific characteristics.

Unlike its name, dark matter isn’t dark. Rather it’s invisible. It’s not antimatter because if it were the interaction with regular matter would annihilate both. In her book Randall describes dark matter as the missing mass that keeps the expanding Universe from flying apart even faster than it is doing today. Gravity is considered too weak a force to explain what astrophysicists decipher from the radio telescopes, scientific satellites, Earth-based experiments and visible light telescopes used today to study the way the Universe works.

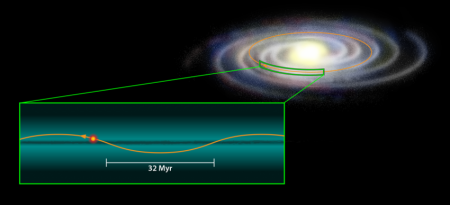

Randall theorizes that dark matter could explain past mass extinctions here on Earth. She proposes that the Milky Way, our galaxy, has a thin parallel dark matter companion resident within it that exerts an influence on our Solar System during its oscillations (see image below) while rotating around the galactic centre. The interaction of dark matter with the outer Solar System’s Oort Cloud, she theorizes, sets long period comets on a path to the inner Solar System where they become objects of doom. As her book title suggests, one of those disturbed Oort Cloud objects may have collided with Earth 66 million years ago leading to the extinction of the dinosaurs.

Theorizing about dark matter has a history since the 1930s. But as of yet we have never seen one elementary particle of the stuff. Scientists don’t know whether dark matter is undifferentiated, that is, a single element, or if it has a parallel Universe of elementary particles equal to visible matter.

It is an anthropomorphic view coming from a creature made of visible matter to think that dark matter might not constitute as rich a material environment as our own. After all it makes up 80% of all matter. In the dark matter parallel Universe there may be numerous dark matter elements with dark stars and even dark planets.

Think this sounds crazy? Remember in our world of the visible, even we cannot see the entire spectrum of light. We don’t see radio waves. We can’t see the infrared part of the spectrum. Yet we know that what is invisible to our eyes does exist and we exploit both radio waves and our knowledge of infrared to design tools we use every day.

Solving the dark matter mystery could yield some exciting and surprising discoveries. Even a whole new periodic table of elements with an opportunity to name all of them. Now that may not excite you but I’m betting there are a whole bunch of researchers out there who cannot wait.