An instrument package residing on the International Space Station (ISS) that was originally looking at airborne dust and its effects on climate has found a second purpose, tracking methane (CH4) leaking into the atmosphere.

Back in February of this year, I wrote about the immediate climate change threat from rising CH4 levels in the atmosphere. At the time I referred to two studies, one highlighting agricultural sources of CH4 leading to atmospheric spikes, and another linking unusual increases to oil and natural gas operations.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency states that pound-for-pound CH4 is 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide (CO2) as a contributor to global warming. NOAA quotes statistics showing CH4 to be 80 times more potent over a 20-year period. The saving grace is that CH4 degrades much faster than CO2 but while it is in the atmosphere contributes to immediate impacts on temperature. That short-term impact is considered by climatologists as a major challenge.

Onboard the ISS is NASA’s Earth Surface Mineral Dust Source Investigation, known as EMIT. Its initial purpose was to study airborne dust and its contribution to climate change. But as NASA Administrator Bill Nelson states, “EMIT is proving to be a critical tool in our toolbox to measure this potent greenhouse gas [referring to CH4] and stop it at the source.”

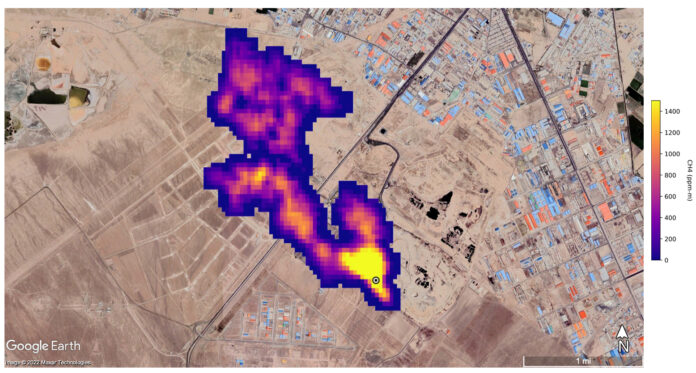

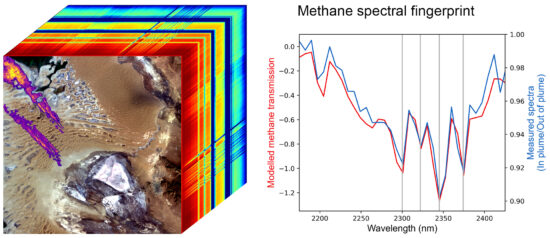

Nelson sees reining in CH4 as an immediate priority. EMIT’s imaging spectrometer sees the gas as it absorbs infrared light to leave a unique spectral fingerprint. In the image below, on the left, you can see CH4 plumes highlighted in purple, orange and yellow. The ones in this image were detected over Turkmenistan. The graph on the right displays two lines, one blue, and the other red. The blue represents actual CH4 levels detected. The red is an atmospheric simulation of expected CH4 levels.

EMIT can scan wide swaths of the Earth’s surface at a time and can zero in on features as small as a football field. The instrument provides pinpoint accuracy in attributing methane sources to human activities. States Andrew Thorpe of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, “Some of the plumes EMIT detected are among the largest ever seen, unlike anything that has ever been observed from space.”

What has EMIT discovered? A representative sample includes:

- a 3.3 kilometre (2-mile) CH4 plume southeast of Carlsbad, New Mexico where a large oil field connected to the Permian Basin is spewing 18,300 kilograms (over 40,000 pounds) per hour into the atmosphere.

- 12 plumes from Turkmenistan oil and gas infrastructure that stretch more than 32 kilometres (20 miles) east of the Caspian Sea and release 50,000 kilograms (110,000 pounds) of the gas per hour.

- a 4.8 kilometre (3-mile) plume of CH4 south of Tehran that is being emitted from a waste facility caused by decomposition.

EMIT is expected to find hundreds of previously unknown super-emitter sites. States Robert Green, of JPL, “As it continues to survey the planet, EMIT will observe places in which no one thought to look for greenhouse-gas emitters before, and it will find plumes that no one expects.”

EMIT isn’t alone in the quest to measure how our planet is changing largely because of human activity. It is one of 25 different scientific packages in orbit around Earth giving us an up-to-date picture of the planet’s climate health. Seven of these reside aboard the ISS.