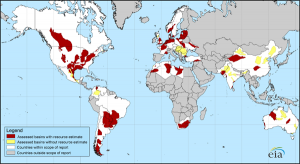

Hydraulic fracturing, called fracking for short, is a mining process designed to release gas and oil trapped in bituminous sedimentary rock formations. Fracking is seen by many in the oil and gas industry as an opportunity to establish energy independence for countries that have vast reserves of bitumen trapped in deep sedimentary rocks.

Fracking technology works as follows:

- A well bore is drilled into a bituminous rock formation.

- The entry well is vertical but to maximize the return horizontal drilling occurs underground within the rock formation.

- A double concrete liner is placed within the initial well bore to minimize contamination of local aquifers.

- A slurry composed 99.5% of water and sand with the remaining portion containing acids and surfactants is injected with pressures up to 10.34 Mega pascals, equivalent to 1,020 atmospheres or 15,000 psi. The high pressure slurry breaks the chemical bond between the rock and bitumen releasing it as natural gas or oil depending on the nature of the rock formation.

- The released bitumen rises under pressure or is pumped to the surface for collection.

- Along with the gas and oil comes the water and chemicals used during the fracturing process.

- This waste water may contain in addition to benzene, toluene, ethyl-benzene and xylene, radium, methane, heavy metals and other toxic substances.

- Waste water may be treated on site in holding and containment ponds or be pumped into trucks and taken away for treatment and disposal. In many cases it is pumped back into the well as a way to increase wellhead pressure and improve oil and natural gas yields. If toxic water gets dumped in nearby streams or if it breaches containment ponds it can contaminate watersheds.

- Where fracking releases natural gas under pressure a byproduct at the wellhead may include airborne chemicals that could be toxic upon prolonged exposure to those working on site or living nearby during exploration and production phases.

So what we know about fracking is the potential polluting effect of the process. Safeguards to address the hazardous chemicals that are byproducts of the process can be monitored and regulated.

But two consequences of fracking that are little understood keep on cropping up. They are:

- Fracking has been associated with contaminated drinking water on farms and in urban centres downstream from drilling sites.

- Fracking has been blamed for a rise in earthquakes in areas where drilling occurs.

Contaminated Drinking Water

When fracking releases oil and natural gas from bituminous sedimentary rocks it also releases other bounded chemicals. In the process of extraction, however, there are numerous complaints about toxic chemicals and methane entering local wells even though they are drawing water from much higher underground sources than those targeted by fracking. In the movie, Gasland, a documentary looking at hydraulic fracturing, the film shows dramatic images of tap water laced with methane that can be lit with a match. Although the fracking industry denies the claim there are numerous cited examples of drinking water contamination in areas where drilling has occurred.

The industry claims that any water pollution evidence comes from variability in fracking methodology around cementing the casing and lining of the well bores. In areas where the bituminous layers are well below the aquifer that water wells draw upon, and sedimentary limestone layers act as barriers to seepage, the industry claims that occurrences of chemicals in drinking water have nothing to do with fracking.

Earthquakes Linked to Fracking

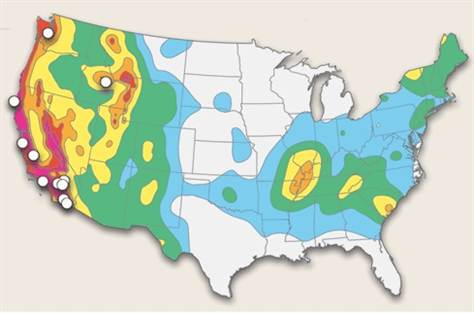

In a 2011 report entitled, Are Seismicity Rate Changes in the Midcontinent Natural or Manmade?, a U.S. Geological Survey team writes that since 2001 there has been a six-fold increase in the average number of earthquakes occurring in the mid-continent. The rate of increase is unprecedented in recorded history and the authors believe the cause is primarily from the well-site injection of fluid used in hydraulic fracturing.

Recent earthquakes in Ohio have resulted in lawmakers temporarily banning fracking in the state. On New Year’s Eve of 2012 a 4.0-magnitude quake was attributed to a fracking process in which waste water collected during drilling was disposed of by injecting back underground for disposal. Previously thought to be a safe practice, geologists and seismologists now believe that this particular practice should be banned.

In November 2011, Oklahoma experienced a 5.6-magnitude earthquake damaging 14 homes. The quake was followed by a number of aftershocks. Oklahoma is normally seismically stable averaging about 50 small quakes annually. But since 2009 that number has suddenly spiked to 1,047. What has been the big change in Oklahoma? Experts point to hydraulic fracturing. Although experts believe the large quake may have nothing to do with fracking, the enormous increase in minor quakes is too coincident with drilling and injection well activity within the State. Oklahoma is home to 185,000 drilling wells and hundreds of injection wells. Waste water injection is considered the primary culprit in this state as well.

Is there a smoking gun to absolutely prove the causal link? Not yet, but there sure are a lot of bullet casings on and underground to suggest a correlation.

This comment comes from a reader who follows my blog through LinkedIn.

Frank Sowa of the Xavier Group writes: Induced Hydraulic Fracturing or “fracking” is NOT more of a problem than the net benefit gained from oil and natural gas extraction!

There are three areas of concern that need to be addressed with fracking (none of which seems to have caught the knowledgeable eye in a way of anything but politicized answers).

Those three areas are: 1) The potential excessive need for a water supply, the follow-up ground and water contamination at well sites and heads, and a slightly higher risk of affecting air quality; 2) Deep earth disruptions and tremors caused by fracking, and the release of radon and other deadly toxins into the rock structures that can seep to the surface over a 40-year period; 3) The quickening of the elimination of the prime source (natural gas) of the finite commodity most-used in polymer (plastics and composite materials) production.

Hydraulic fracturing is the propagation of fractures in a rock layer caused by pumping a pressurized fluid into them and shattering them. Creating fractures from a wellbore drilled into reservoir rock formations deep in the earth via high-volume fracking, can use as much as 2 to 3 million US gallons (7.6 to 11 Ml) of fluid per well. If the water is not recycled, that is a tremendous amount of potentially clean potable water that is contaminated at each well. The mitigation and recycling technologies are cost-effectively available, however, to treat this water, extract the toxins and contaminants and recycle the water for more fracking, thereby overcoming this issue if regulation and environmental watch groups along with the energy companies who own the wells and/or perfrom or oversee the fracking keep this under tightened control. Politically, all governments who allow fracking in their region should set up some form of interest-bearing mitigation fund that can be tapped short-term and long-term to find R&D ways to mitigate issues (this fund could be funded via extraction taxes, business taxes, sales taxes on extracted products, shipping tariffs, etc.). The drillers also should be bonded and have fracking insurance that pays for damages to personal or collective property on damage.

Continued R&D is the only way to resolve the second mitigation challenge — that of earth crust disruptions (earthquakes), tremors, and release of deadly (Love Canal-style) toxins and Radon gases. Many of these problems won’t be evident for 40 years — but after that timeframe there may be 12 mile radii around well heads that may become uninhabitable. This happened in early Barnett Shale fracking sites in Texas. With a 40-year lead time (if society doesn’t wait until after the fact to seek a solution), we should be able to identify the means to resolve this (as high-priced solutions were developed for nuclear waste similar to Barnett Shale wastes by Westinghouse Electric).

As for the third challenge, we will and are using up our primary fossil fuel supply for polymer chemistry to provide energy independence. The good news spin off, however, is that fracking lowers the commodity pricing creating a resurgence of possibilities for chemical and polymer manufacturing (and jobs) again reborn in North America.

Thus financially, if acted upon as a holistic system — fracking provides more of a cultural ROI, than a destructive social problem for the short-term, and the long-term future. If however, we as a society fail to act intelligently to anticipate and resolve short-term and long-term issues. We will only have ourselves to blame when there are severe drinking water shortages, when water/land/air become contaminated, when whole regions become uninhabitable, when highly populated areas have tremors and earthquakes that cause billion dollar catastrophes to buildings not equipped for such ground displacements, when we can no longer make polymers, plastics, and composites that are now integrated into everything.

I appreciate the additional knowledge you bring to this discussion. Your conclusions that the risks are mitigated by the temporary gain in moderated pricing is not one with which I agree. Production from fracking does not contribute that much to the total use of fossil fuels today and the technology in common use at present is not fullproof.

Further comments from Frank Sowa from the LinkedIn page:

Frank Sowa writes: My conclusions are drawn more from an engineering and understanding of the timeline of the innovation cycle for a system: that is — idea > Invention > innovation > imitation. That cycle traditionally took 10-20 years in the 20th Century. Today, that cycle is cycling at 2 years and the emergent concepts are cycled in as little as seven weeks.

When you state: “Your (my) conclusions that the risks are mitigated by the temporary gain in moderated pricing is not one with which I (you) agree. Production from fracking does not contribute that much to the total use of fossil fuels today and the technology in common use at present is not fullproof,” you appear to be coming at the problems and solutions in an old school linear extrapolation fashion, rather than a new school non-linear parallel system algorithmic approach.

Basically, your logic is based on the finances within the market today. Based on equity valuation of natural gas and oil, and linear projections by financial houses — you state that production from fracking does not contribute to the total use of fossil fuels TODAY! (Yes, you are right.)

Fracking moved on the 20-year 20th Century linear innovation cycle. It moved out of the basic science R&D lab and into use in the Barrett Shale Fields in Texas as an experiment in 1947. It as piloted (in the invention segment of the cycle from 1953-1957) … a 10-year cycle. It was put in comprehensive production in 1958 (about the time sweet oil in the Middle East took off which took interest away from it making it lie dormant). It was dormant basically until Halliburton assisted the Kuwaitis in an experiment in side drilling and fracking that opened up the Iraqi reserves to Kuwait along the border in 1987-90 — that was much of the cause of the Gulf War in 1990. Now, as new resources are sought because globally the emerging countries are demanding more fossil fuels, it has grown in interest again — but that interest is less than 3 years old!)

You then said that “the technology in common use is not “fullproof.” To that part of your comment I wholeheartedly agree. But, I also believe that with the new innovation cycle, and with the 40-year window that I mentioned in my first posting — that there IS ample time to correct the technology in common use BEFORE there is a crisis. (A solution will NEVER be fullproof. But, it should meet Six Sigma, and I believe that if a mitigation approach is actively pursued, it should be had in six-eight years.)

So, back to you initial question: I believe based on evidence that “Induced Hydraulic Fracturing or “fracking” is NOT more of a problem than the net benefit gained from oil and natural gas extraction!”

The costs to improve the mitigation technologies (all of which are already beyond the higher-cost invention phase and well into the efficiency-building lower-cost mainstreaming innovation phase) (if politics doesn’t get involved, or market greed and speculation unrealistically alters the market forces) should have less of a societal problem or profit impact than the net benefit of shifting to a cleaner and home-based energy reserve.

Hello lenrosen4

I liked your article and would like to comment on your “smoking gun”- I was brought to this link because this morning, 4/13/14, a 4.9 hit near Challis, Idaho – I compared it to your map above on Bing and can’t help but notice how close the one white dot is to Challis- your map and story are 2 years old- Coincidence???? – I don’t really know a lot about this subject, but had to post incase you hadn’t seen it.

Thanks

Hi Amy, There is a correlation between earthquakes and fracking operations but these usually are small seismic events. Where is the suspected link? The earthquakes that have struck Ohio, Oklahoma and Texas suggest that the extraction process may not be the cause of these man-made seismic events, but that the millions of liters of chemical-laced water that gets injected into waste wells, a byproduct of the fracking process, is the likely culprit. These waste water injection operations happen wherever fracking occurs.