Heat pumps have been around for more than 170 years. They absorb heat from the outside and transfer it indoors in winter. They extract heat from the inside and push it outside to cool interiors in summer. The first use of heat pump technology for heating homes and buildings occurred in 1928 in Geneva, Switzerland. A heat pump installed in Zurich in 1937 worked continuously until 2001. But widespread adoption has remained elusive elsewhere.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that heat pump models for homes first appeared in North America. An oil crisis in 1973 stimulated sales with adoptions in places like Japan, the United States, and Europe. This generation of heat pumps used inverter-driven compressors to save electricity while running continuously to provide heat or cooling as needed.

Today, variable-capacity ground, water and air-sourced heat pumps are found in homes and businesses, an alternative to using fossil-fuel-based heating.

Using Large-Scale Centralized Heat Pumps

In the village of Swaffham Prior in the United Kingdom, a centralized heating network has been installed (see picture above) to warm homes. The use of a large-scale centralized pump is a pilot project to demonstrate the effectiveness of this type of deployment which is aimed at reducing the cost of moving homes off oil and gas heating while saving costly home retrofits associated with individual heat pump installations.

The heat pump in combination with solar panels, electric boilers and underground storage is generating 1.7 megawatts to produce heat that travels through pipes installed underground with village homes connecting to them and their existing home radiators and hot water appliances. No home retrofits are needed. So far, one-third of the village has been connected with 200 remaining homes to be added. Before this heating network existed, Swaffham Prior homes used oil furnaces.

In the United Kingdom today, fossil-fuel-home heating predominates with 74% of homes heated using natural gas. The heating of homes and buildings accounts for one-third of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. In ramping up heat pump use, the country is looking to go from 55,000 annual installs in 2023 to 600,000 homes by 2028.

Heat Pumps Key to Transitioning from Fossil Fuels to Clean Energy

What makes heat pumps so attractive? I can think of 4 things right away.

- They concentrate heat energy from air, ground or water and transfer it into a home or building with efficiency. Ground sources are more efficient than water or air when considering the type of heat pump to adopt.

- Heat pumps convert a kilowatt of electricity into between 3 and 5 kilowatts of equivalent heat. That compares to a 1:1 ratio for baseboard electric heating and 1:0.9 for heating using natural gas.

- A well-insulated building using a heat pump can maintain its heat almost for free while producing no carbon emissions.

- A heat pump provides more than just warm internal air. It also acts as a replacement for separate gas-fired or electric water heaters.

IEA is Big on Heat Pumps at COP28

The International Energy Agency (IEA) recognizes that heat pumps are critical for decarbonizing heating. It estimates that heat pumps can eliminate 500 Megatons of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions annually by 2030 which equals the carbon emissions of all the cars on the roads in Europe today.

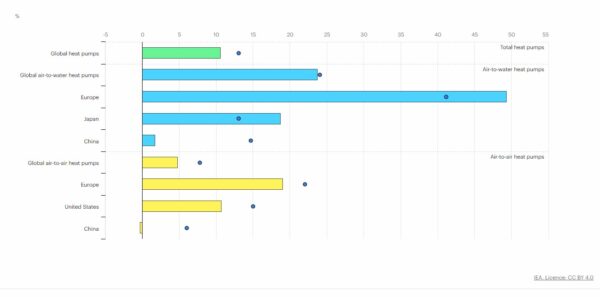

The following IEA-created graph shows the percentage growth in heat pump deployment for 2021 and 2022 in selected countries and by type.

Overall deployments last year grew 11% with record adoptions in Europe, Japan and the United States. But what will be needed to accelerate the decarbonization of heating is heat pump adoption to triple between now and 2030 to cover 20% of global heating needs.

The impediments to heat pump adoption include:

- a need to implement supporting infrastructure and electrical grid capacity as homes and buildings switch their heating from natural gas and oil.

- the high cost of retrofits of homes and buildings.

- the critical lack of expert labour, companies and operators to meet the growing demand.

- the need for manufacturing to quadruple by 2030 to meet global targets.

- the requirement to replace hydrofluorocarbons (HFC), a potent, short-lived greenhouse gas, as the commonly used refrigerant with one that doesn’t contribute to short-term global warming spikes.

The IEA in presentations at COP28 is recommending:

- governments develop financial assistance programs to speed up heat pump adoption.

- reduce the cost barrier making adoption more affordable.

- target legacy residential homes, multi-unit dwellings and commercial buildings.

It sees district heat networks like Swaffham Prior as low-cost alternative solutions to individual home and building installations for use in cities and rural areas. Large-scale heat pump installations are less expensive to implement and remove retrofit costs from the equation.

The IEA is asking those attending COP28 to develop stronger international collaboration, more data collection, and sharing of best practices to accelerate decarbonization through global heat pump adoption.