January 20, 2019 – In 2015 my wife and I booked a river cruise that had us commuting from Prague to Nuremberg and then departing from there on the Rhine before transferring by canal to the Danube. We had chosen to travel in September because the heat of the summer was supposedly nearing an end, and the river levels at that time of year were considered stable. Neither of these two facts was borne out. A persistent heat wave had temperatures in the mid to high 30s Celsius (well over 90 Fahrenheit) every day. And with no rain because of prolonged drought, river levels were lower than normal.

So we never embarked in Nuremberg and in fact were bussed to Passau on the Danube where the river was deep enough for our boat’s passage. Our river cruise became a mixed bag of bus trips to the cities and towns we couldn’t access because of low water. And then when we headed downstream to Vienna and beyond to Budapest, our boat struck bottom about 75 kilometers upstream from Hungary’s capital and once more we were on buses.

Was this a normal occurrence? We were assured not, but it appears to becoming the new normal for Europe’s two major tributaries, the Rhine and the Danube. These two are to Europe what the Mississippi-Missouri-Ohio River system is to the United States or the St. Lawrence-Great Lakes to Canada. They are critical transportation arteries filled with barge traffic moving raw resources, manufactured goods, and people. And when there is low water, or high water the transportation network they represent grinds to a halt.

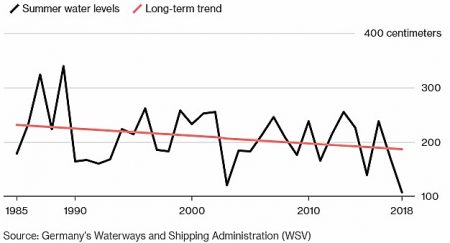

This last summer has proven to be the exception that is becoming the rule. A prolonged summer drought shut down river traffic for nearly a month. A car ferry operator on the Rhine named Kevin Kilps is quoted in a Bloomberg article stating, “You can see the water levels are lower each year…It’s scary to watch the climate changing.”

Low water levels on the Rhine impact Germany’s industrial sector in significant ways. Companies like Daimler, Robert Bosch, Bayer, BASF, ThyssenKrupp, and Volkswagen are dependent on the river as a transportation artery. BASF’s CEO, Martin Brudermueller, blamed the low water in the Rhine for nearly 250 million Euros ($280 million USD) in increased operational costs. With water depths at a 12-year low, much of the river traffic consisting mainly of barges was unable to navigate the full length of the river, almost 1,300 kilometers. Instead, barges which can carry much larger loads than trucks or trains could no longer be used to transport raw materials and finished goods.

So what is happening to Europe’s two great rivers? Both headwaters, the Rhine and Danube, originate in the Alps. They are glacier and snow-fed. And the alpine glaciers of Europe are receding because warming temperatures are melting the ice faster than the snow can replenish them. In twenty years what the Rhine and Danube have been recently experiencing will become the norm as the reliable cycle of ice-fed rivers is disrupted as alpine glaciers disappear.

This problem isn’t limited to the Rhine-Danube. Asia’s great rivers from the Indus in Pakistan, to the Yellow in northern China, have their sources in the Himalaya’s fed by glaciers that are similarly receding. The cause: atmospheric warming.