November 27, 2014 – The list of diseases appearing in unfamiliar places continues to increase for lots of reasons. These include:

- Human-engineered water projects such as dams, canals and irrigation.

- Agricultural intensification and the use of insecticides.

- Urban crowding and poor sanitation.

- Deforestation.

- Reforestation.

- Changes in precipitation and weather patterns.

- Atmospheric and ocean warming.

We humans have been aware that conditions we create often lead to disease outbreaks. When Bubonic plague struck Europe in the Middle Ages it tended to be a city and town-centered disease. That’s because the carrier was a flea found commonly on rats, and rats were ubiquitous with town and city life. The nobility fled the towns to their country estates to avoid infection. The same thing occurred during the period of the Roman Republic and Empire. Malaria commonly occurred along the rivers and in the marshes of Italy. Roman senators retreated to their hilltop villas each summer to avoid contracting it. These societies may have not identified the root cause of malaria and Bubonic plague, but they recognized the correlation between outbreaks, seasons and locations.

In the 19th century we began to uncover the root causes, what we now refer to as vector-borne transmissions. Those vectors are the pathogens (the bugs) and their hosts (insects, rats and other animals). When we create conditions receptive to optimal reproduction for the hosts, humans living in proximity become infected. And then humans can themselves become the direct transmitters of infectious pathogens.

Of the reasons for changes in disease patterns described above our focus today will be on those attributed to a changing climate. Climate and infectious disease transmission have always been linked. Climate variability has frequently been associated with disease outbreaks. But these outbreaks have largely occurred within specific geographies and climate zones. But scientists are now witnessing a new variable in studying climate and disease, and that is disease creep.

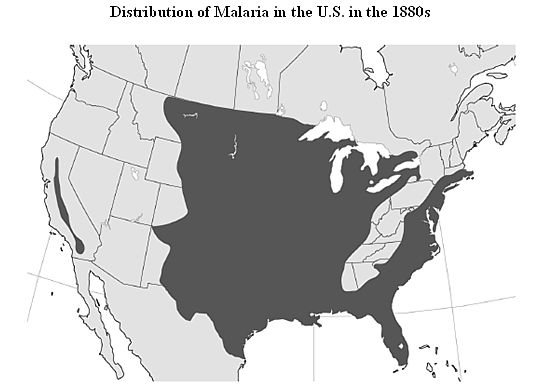

Malaria was once common throughout much of Europe and North America. Look at this map of malaria distribution in North America in the 1880s.

It occurred in lower elevations and where host mosquitoes resided in marshes and water courses. But human engineered water projects tamed these environments and the introduction of insecticides eventually confined malaria to sub-tropical and tropical parts of the planet where it remains a major killer to this day, taking the lives of over 1 million each year.

Today we can predict malaria outbreaks after El Nino events. Data collection over the last two decades shows a 500% increase in the year following these surface warming events in the Pacific Ocean. We also can predict outbreaks associated with thhe annual Indian Ocean monsoon which impacts much of the Indian subcontinent. These are just two examples of short-term weather and climate variability evidence in the spread of disease.

But what about long term climate change? This is where disease creep manifests itself. Global warming influences habitats.

For example a warmer ocean yields higher incidence of red tide outbreaks. And a warmer atmosphere changes growing seasons for plants, causing many species to expand their ranges poleward. In turn the insects and animals that forage and feed on these plant species also migrate. Along with the opportunity for expanded range for these species comes the pathogens they incubate or carry.

The result, changes in infectious disease patterns for a wide variety of diseases including:

- Malaria

- Cholera

- Schistosomiasis

- Helminthiasies

- River blindness

- Hemorraghic fever

- Dengue fever

- Leishmaniasis

- Oropouche

- Lyme Disease

- Hantavirus

- Rift valley fever

- Yellow fever

- Chagas Disease

In this month’s Discover Magazine, Rebecca Kreston, an epidemiologist and tropical disease specialist, writes about Chagas in America. Chagas is caused by the pathogen, Trypanosoma cruzi, a protozoan that is hosted by the Kissing Bug. The image below credited to Thierry Heger shows the various stages of the bug’s growth to fully mature adult.

Once a disease found only below the Rio Grande, changing climate conditions have led to disease creep. Today occurrences of the pathogen and its host can be found in Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Mississippi and Arkansas. In Texas canine animal shelters are discovering that a large number of the dogs are now host reservoirs for the pathogen. And since dogs and humans are socially connected it is no surprise that among Texans, one in every 6,500 blood donors tests positive for the Chagas parasite. That compares to 1:300,000, the estimated number of those infected with Chagas across the United States today.

In a recent Baylor University study, 17 people testing positive for Chagas were followed. Of those, 40% developed symptoms associated with the disease. These include changes to heart rhythm including arrhythmia, a potential life threatening cardiac condition. In those 17 few had traveled abroad so the source of the infection was homegrown. A number lived in rural settings and were involved in significant outdoor activity. These individuals may be at greatest risk to exposure to the Kissing Bug and its bite. The Baylor study was on adults, but according to the Mayo Clinic, it is children who are most susceptible to contracting Chagas and if undiagnosed and untreated, in these young people it can cause not just cardiac but digestive problems.

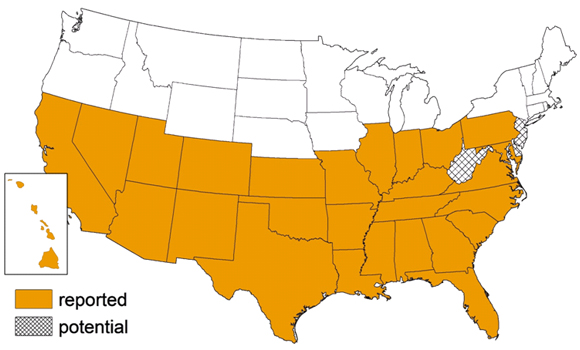

Just how far will Chagas creep? The map created by the Atlanta, Georgia-based Center for Disease Control below shows where Chagas has been reported in the United States and where it is expected next. No longer a disease of the tropics and sub-tropics, climate change has extended its range to temperate latitudes.

In Kreston’s article she points out “there are no established systematic treatment plans” for this disease.

More disturbing is the fact that Chagas isn’t alone in posing a growing threat to temperate climate zones. Dengue fever, once confined to Southeast Asia and islands in the western Pacific Ocean, is now found throughout Central America, the Caribbean, South Florida, Hawaii and South Texas. Dengue is transmitted by a species of mosquito, Aedes aegypti, whose range has expanded along with increased warming of the atmosphere. In its worst form Dengue causes hemorraghic fever with bleeding under the skin, and from the nose and mouth (symptoms similar to Ebola).

With malaria and Dengue fever we may soon have vaccines to help us fight them off. But for so many of the tropical diseases that are creeping poleward, we have yet to devise effective cures or preventives. In calculating the cost of mitigating anthropogenic climate change, therefore, we have another number to add to the growing list, the medical infrastructure and human cost of disease creep.