October 12, 2019 – It has been a frustrating five years of searching for the latest research into regenerative medicine, and stem cell science, as I have put off making the decision to have my knee replaced with an artificial joint. It seems so many mouse-based research studies have shown that our bodies can regrow damaged cartilage in joints. So many clinical trials performed on a limited number of patients have further demonstrated the viability of a combination of implanted matrices and stem cells that could make knee replacement obsolescent.

But unfortunately, none of these advances are even close to becoming the treatment of choice in dealing with patients like me who have virtually no cartilage remaining in one of my knee joints. What the X-rays show is bone-on-bone, and what keeps me going is periodic cortisone injections and a daily application of pain killers plus CBD oil.

In less than two weeks I go for my third re-assessment knowing that this exercise is purely a formality before I get introduced to an orthopedic surgeon who will tell me that regenerative treatments remain a decade away.

I was told the same thing five years ago at the first assessment.

Should I be surprised about the ten-year forecast?

Consider that a decade ago we were told that fusion energy was only a decade away and that we were told this again this year…only a decade away. This seems to be a common mantra for so much of what we are told by scientists and engineers when it comes to innovation and breakthroughs.

Just like my knee needing a better solution than cut and replace, the world needs an energy solution like fusion to save it from the tyranny of fossil fuel companies and the pushing of their addictive product on the world economy as they lobby governments to do little if anything to stop the deadly impact on climate of their products. (Please excuse my perpetual rant on this subject.)

Having said all this, here’s the latest research piece in developmental biology that suggests we have a latent ability to regenerate joint cartilage in the same way salamanders do to regrow a lost tail or limb.

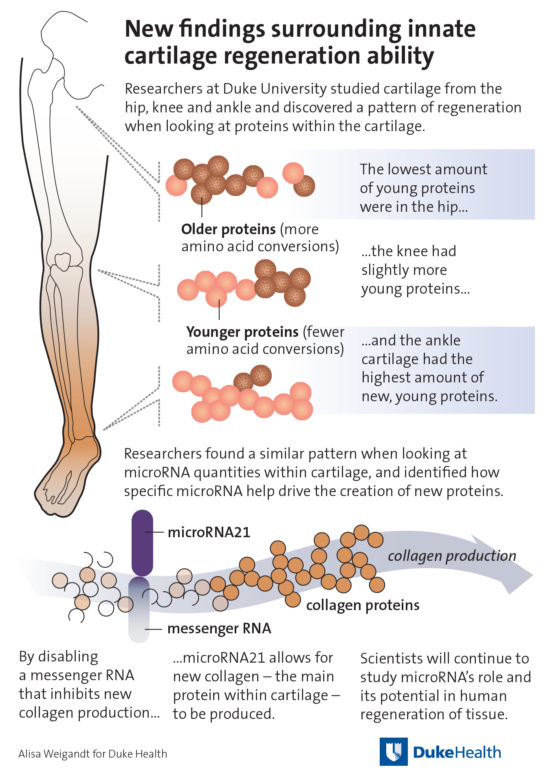

In a paper entitled, “Analysis of ‘old’ proteins unmasks dynamic gradient of cartilage turnover in human limbs,” Virginia Kraus, and four other researchers from Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, and Lund University, Lund, Sweden, have just published results that show proteins associated with microRNA reflect an “innate tissue repair capacity in human lower limb cartilages.” They are not saying that we have a salamander’s propensity to regrow an entire limb, but rather limited regeneration capacity for joint repair.

In an interview published in The Scientist, Kraus states, “We believe that an understanding of this ‘salamander-like’ regenerative capacity in humans, and the critically missing components of this regulatory circuit, could provide the foundation for new approaches to repair joint tissues and possibly whole human limbs.” This is a bit of hyperbole considering what is actually stated in the research paper itself with an emphasis on limited regeneration capacity.

So how does this microRNA and young protein discovery work?

The researchers discovered an abundance of microRNA along with young proteins that block messenger RNA from inhibiting production of new collagen.

With this microRNA, Kraus suggests it can be “injected directly into a joint to boost repair to prevent osteoarthritis after a joint injury or even slow or reverse osteoarthritis once it has developed.”

What has been further discovered is that the phenomenon of young proteins to facilitate regrowth and repair appears in greater volume the further from the body’s central trunk. So translated, that means less of the proteins in the hip joint, more in the knee, and even more in the ankle. The illustration below visually describes the discovery very well.

So maybe I can take the research paper with me when I go to my next knee assessment and ask the orthopedic surgeon to comment. I’m betting the answer will be, “it’s a decade away.”