August 14, 2018 – When you read the title of this posting you probably were wondering what the heck I was thinking. But bear with me on this. For those of you who are unaware, I am a history graduate with my focus of study, the Roman Empire, the rise of Islam, and the transition to the Medieval World. From the lectures I sat in on, and the reading I did about the decline and fall of Rome, there was very little in the way of research tying the fall to climate change, or pandemics. Instead, we were fed stories about lead in Roman plumbing, about militarization of the imperial leadership, about internal unrest and civil wars, and about overwhelming barbarian pressure to cross the Rhine and Danube frontiers.

There is, however, another narrative described by Kyle Harper, Professor of Classics at the University of Oklahoma, in a recently published book entitled The Fate of Rome. The story it tells describes the golden age of Rome’s empire as coincident with a period known as the Roman Climate Optimum, equated with its equivalent, the Medieval Warming Period which has been well described in recent history texts. The Roman Climate Optimum was a benign, warmer, wetter period in and around the Mediterranean Sea, the heart of the empire. And during this period the empire’s population reached its maximum, probably close to 100 million in population. Egypt was the breadbasket of the empire with annual bumper crops blessed by the yearly Nile inundations which varied little throughout the period.

What affected the Empire’s weather in such positive ways? The likeliest explanation is an environment that saw little in the way of variable conditions imposed on it. There were no major volcanic eruptions on the planet that could alter the amount of solar radiation reaching the surface. Annual monsoon records in the Indian Ocean showed consistency. Also true was the reliability of the North Atlantic Oscillation which proved to be a steady benign influence on the Mediterranean climate.

The growth in population, and the expansion of trade with other parts of the planet including Han Dynasty China, India, and Africa, created an avenue for disease transmission along trading routes. The first of many shocks to strike the Empire in the latter part of the 2nd century was a pandemic described as the Antonine Plague. Disease proved to be more destabilizing than all of the court intrigue and military maneuvering typically described in Roman history books. Added to disease came climate change with changes to the North Atlantic Oscillation, periodic failures of the Indian Ocean monsoon, and a resulting decline in crop yields first and foremost in Egypt, and then elsewhere in the Empire.

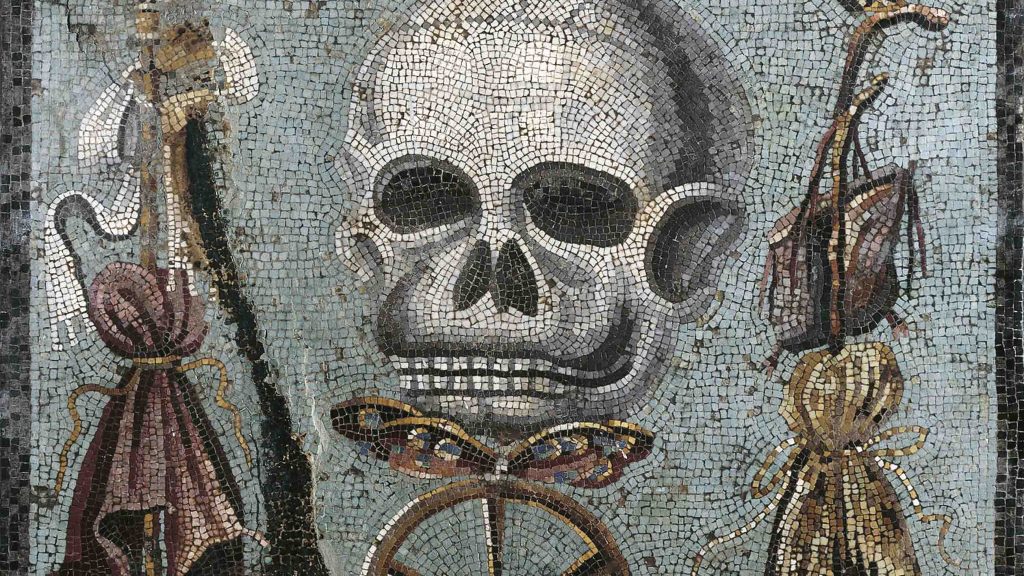

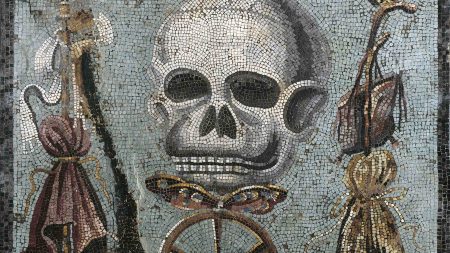

These were but the first of many environmental and pandemic convulsions to beset the Roman world from the late 2nd-century to the rise of Islam in the 7th. When the Antonine Plague ended the Empire recovered to a degree but never to the peak level of population known in the mid-2nd. Then the mid-3rd-century experienced drought and the return of a pandemic, the Plague of Cyprian. Once more the Empire reeled and saw its population drop dramatically. Changes in political leadership and an almost total dissolution of the Empire followed only to be restored in the late 3rd and the beginning of the 4th century.

Add to this decadal drought in the Central Asian steppes and you have the beginning of the mass migration of tribal groups pressing in the east on the borders of Han China and in the west on the Roman frontier. Waves of mass migrations reached the Rhine and Danube. A pandemic-depopulated Empire took many of these tribes in having them serve in the military to defend the frontier often against their compatriots. Rome granted these refugees of climate change citizenship, land, and homes in plague-emptied villages and towns. In these post-pandemic times, it was no wonder that many in the Roman world turned to the religion of Christianity in search of a better future. Writing at the time describes the beginning of the end of days.

The Empire managed to recover and in the 4th century recentered itself on Constantinople, the new Rome. This was coincident with a return to a more benign climate in the Nile valley and through much of the eastern Roman world. That was not the condition of the steppes of Asia where a megadrought forced native populations to search for greener pastures and water. The pressure on Rome’s frontiers was relentless.

Then came the Huns from the Central Asian steppes, who in the late 4th and beginning of the 5th century, defeated Roman armies and sacked Rome itself. The Empire split in two with a western and eastern half. Roman authority in the west slowly disintegrated as tribes from beyond the Rhine and Danube continued to press into the imperial heartland. By the late 5th century the emperor of Rome was no more. Legions and garrisons in different parts of the western half of the empire continued to hold out for decades before finally the waves of new immigrants overwhelmed them.

The Eastern Roman world remained intact and by the beginning of the 6th century sufficiently recovered to begin a reconquest of the western half of the Roman world. Spain, North Africa, and Italy were once more part of the Roman world. But another pulse of climate change and pandemic ended the restoration attempt.

The first known global pandemic, the Bubonic Plague, arrived along trade routes bringing the bacterium Yersinia Pestis spread by fleas carried on the bodies of rats. When the rats died from the plague the fleas transferred to human hosts. Minimal estimates of lives lost believe 50% of the empire’s population died. Constantinople lost more than half of its population. Cities of the Eastern Mediterranean such as Alexandria and Antioch were turned into ghost towns. The reach of the Bubonic Plague ended at the edge of the Arabian desert leaving places like Mecca and Medina unscathed. The plague was facilitated by climate change. It spread from its Asian origins to the Roman world along the same routes of migrating tribes fleeing megadroughts.

Without the Bubonic Plague facilitated by climate change it is doubtful that Islam would have risen to succeed the Roman Empire in Northern Africa, and the Middle East, let alone conquer Persia which was also subjected to the pandemic. One can draw a conclusion that the caprice of nature was more responsible for the end of the Roman world than all the political subterfuge and civil wars that we read about in Roman history. Climate and pandemics don’t appear in these books that describe Rome’s emperors and its history of conquest and triumphs.

Why is that?

Because it is only recently that climatologists and epidemiologists have looked into the past to understand historical patterns in weather and disease transmission. In the study of Rome, they have found a stark example of how climate change can alter history in dramatic ways. Climate change and accompanying pandemics did more than destroy empires. They also may have been the driving force for the arrival and spread of universal faiths as in the case of Christianity, and later Islam.

So what does this have to do with the present?

Humans today are altering Earth’s climate through the burning of fossil fuels and the carbon emissions these fuels create. Not only is the climate in play, but so is much of Earth’s biodiversity, and ocean sea levels. Changes in precipitation patterns, megadroughts, a population approaching 7.5 billion and climbing, creeping food insecurity, mass extinctions of fauna – these are characteristics of the present Earth.

The Romans of the mid-2nd-century didn’t see what was coming. The Romans in the 4th were less certain and found comfort in a new universal faith. The Romans of the 6th were devastated and never recovered. Are we the people of the planet to be equally blind to what may lie ahead if we don’t alter our course, or should we be accepting of a fate produced by our own unwillingness to alter course?

[…] What part have pandemics played in history? Kyle Harper, a Professor of Classics at the University of Oklahoma, published a book entitled The Fate of Rome in which he described the 2nd Century CE Antonine Plague that devastated and depopulated the Mediterranean world leading to a prolonged period of migration of populations from outside it destabilizing the empire into the late 3rd century. […]

[…] with a changing climate? Although this new paper doesn’t attempt to draw a link, there is significant evidence that warming periods, external population shifts, local population growth from increased […]