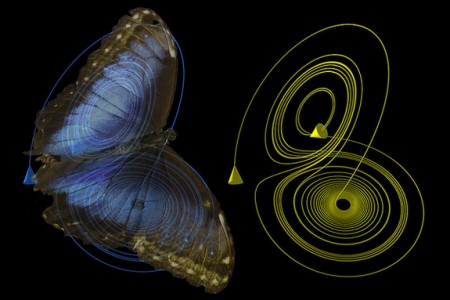

October 22, 2015 – In the last two decades as the United States and other countries have sent Earth-observation satellites into near-Earth space we have learned just how interconnected acts on one side of the globe lead to consequences elsewhere. Known as the butterfly effect, where the batting of the wings of a butterfly in Indonesia lead to a tornado touching down in Texas, has often been discounted by scientists. But there is something to this but it isn’t on the scale of the stroking of the wings of a single butterfly.

Today we take data from observation satellites to do pattern analysis and this allows us to derive some pretty interesting conclusions. What we are learning is how climate influences us and how we influence it. And in addition we are learning that a physical phenomenon that is not weather happening in one area of the globe can have significant impact on climate elsewhere. For example, here are some interesting observations from studying El Nino events in the Pacific Ocean over the last few decades. El Ninos correlate directly with extreme weather patterns from Australia to California to eastern North America and beyond. Here are just a few of those correlations:

- variability in fire seasons occurring in the western United States and Canada, Brazil and Indonesia.

- increases in ground level ozone pollution associated with respiratory disease and asthma in urban centres.

- collapse of the Peruvian fishery.

Since we are using the El Nino as the example, exactly what is it? First observed off the coast of Peru and Central America it refers to a warm ocean current that appears near Christmas (hence El Nino, referring to the birth of the baby Jesus). The Peruvian fishery collapse associated with this invasion of warm water has an enormous impact on those countries dependent on this food and revenue source. But the impact of an El Nino is far more pervasive than that. It influences the path of jet streams over North and South America. It raises sea levels causing storm associated higher than normal coastal flooding and erosion. It changes winter in western North America making it warmer and drier and encourages the opposite impact on winters in eastern North America which become colder and wetter (remember the recent winters eastern North America has experienced and you begin to see what I am talking about).

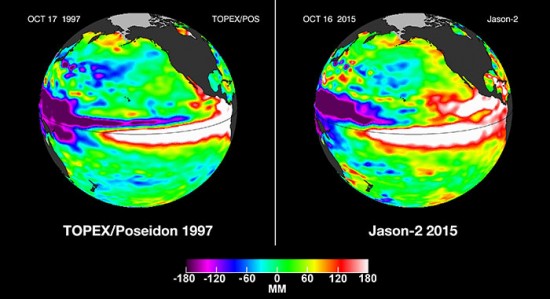

Where El Nino events in the past might have occurred in cycles of up to seven years, now it appears the time between cycles is shortening. A new El Nino event for the Christmas period of 2015 has been observed by current Earth observation satellites, one of them Jason-2, a NASA and NOAA joint project. This new El Nino appears to be the most significant since the late 1990s and is expected to impact precipitation and temperatures across all North America.

NASA’s fleet of Earth observations satellites are tracking the impact of this El Nino. For example, one satellite measures precipitation every three hours. Another reports surface soil moisture levels. Data collected will help scientists, engineers and farmers put into place adaptation and mitigation strategies to offset El Nino climate impacts.

To get a sense of how significant this year’s El Nino will be take a look at the comparison based on data collected from 1997 with that of the present. The large white bands spanning the Earth’s equator show the extent of the ocean surface warming and this year’s is bigger than what was observed in 1997, the former record holder.