April 18, 2018 – In Canada the country is facing a confrontation that includes the federal government, two provinces, First Nations, and environmental groups over a pipeline from Alberta’s oil sands to a shipping terminal on the Pacific coast. Meanwhile, energy producers in the country are hedging their bets on future pricing for oil and gas by locking in long-term pricing for contracts of delivery not knowing what the outcome of the oil sands and pipeline kerfuffle will be, and what regulatory future and pricing on carbon will be. And then there is Russia, Saudi Arabia, and other Middle East oil producers trying to figure out if there is a long-term future for their fossil fuel resources or will global efforts to fight climate change leave them with hundreds of billions of barrels and trillions of cubic feet forever stranded. And finally, there are the oil majors themselves, ExxonMobil, BP, Chevron, Royal Dutch Shell, Total, and others who are trying to hedge their bets by spending money in new energy projects from solar, wind, geothermal, and storage. They too see the need to be making a faster turn to greener sources of energy because they are not sure how long they can hold back the regulators and legislators of the planet from making their fossil fuel-based business model no longer viable.

Alberta, Canada, British Columbia, First Nations and the Trans Mountain Crisis

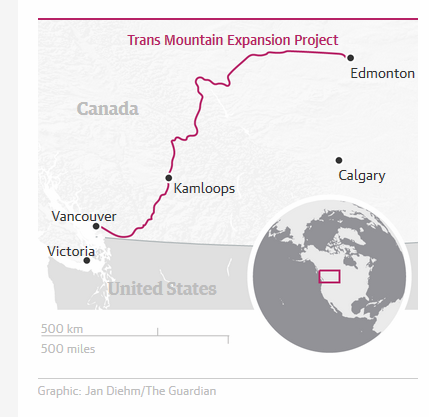

The Canadian government approved the building of a second Trans Mountain Pipeline last year to follow the route first laid down some years ago and tripling the amount of oil traversing this right of way to a Pacific Ocean port in British Columbia. But politics and the environment have gotten in the way.

The province of British Columbia elected a minority progressive-socialist government supported by three Green Party members. The bargain struck for the government included stopping the pipeline from being built. The justification given was to ensure Pacific coastal waters were protected from oil spills like the Exxon Valdez. The opposition to the pipeline included First Nations living along the pipeline’s right-of-way. Environmental activist groups including Greenpeace, Avaaz.org, 350.org, and others, drew a line in the sand aimed primarily at the oil sands seeing the pipeline as an enabler of one of Canada’s largest sources of carbon emissions.

The federal government approval was done in the “nation’s interest.” Now the quarrel among the parties is leading to a constitutional crisis abetted by Trans Mountain’s recent announcement that it intends to pull the plug on the project if there is no way forward by the end of May 2018.

Can a provincial government block federally-approved projects on their own territory? Can a First Nation do the same?

The bargain to keep the minority British Columbia government in power is not the only one that has been made. Alberta and the Canadian government have also got an agreement. In return for pipeline approval, Alberta has imposed a price on carbon emissions within the province and has agreed to phase out its coal-fired thermal power plants.

Alberta believes its economic future remains tied to the oil sands and shipments of its products out of the country to world markets. But without access to tidewater, Alberta’s sole means to export continues to be through the United States with heavy price discounts caused by competition from American fracking operations. The end of being landlocked means the end of American dependency. It means Alberta can get world pricing. It means more oil being produced from the oil sands resource. And it means a provincial revenue windfall from taxes on output.

There is a problem when an economy has most of its eggs in one big basket and a few small ones elsewhere. That is an apt description for Alberta. But the province has other eggs to hatch which could become world-beating industries in the battle to mitigate global warming. Read a posting from last December on this website where it describes Carbon Engineering, CO2 Solutions, and Shell’s Quest carbon sequestration technologies, all Alberta-based ventures. Each of these is a state-of-the-art business that could in time replace the jobs and revenues currently produced by the oil sands. But unfortunately, changing the Alberta economic paradigm from fossil-fuel to low-carbon-solution technologies seems to be far from the minds of those in the boardrooms or political offices of the province.

The conflict over Trans Mountain is likely to produce no winners among federal, provincial, First Nation, and municipal governments, the principal parties to the conflict. And certainly, the environment is bound to be a big loser as well. For those of you who are readers from outside Canada, I promise to keep you informed about the outcome of this kerfuffle.

In Part 2 of this series, I look at how fossil fuel energy producers are locking in long-term pricing as a hedge against the uncertainty brought on by climate change and efforts by governments and citizens to move to low-carbon energy alternatives.