Starlink is an ambitious project to connect the entire world to high-speed Internet over a satellite network containing tens of thousands of telecommunications satellites. Called a constellation, SpaceX has been launching now for several years 49 at a time. The number of operational satellites in low-Earth orbit is approaching 2,000 and represents a disruptive innovation that could turn the telecommunications industry on its head. The most sincere type of flattery the company can get is the number of competitors who are making a similar effort to put their own satellite constellations into near-Earth space.

But in the news this week, SpaceX announced a failure to successfully launch. It’s not that Falcon 9 didn’t do its job. Both stages of the rocket worked perfectly and the first stage was landed with accuracy. But it appears the company didn’t check the space weather report. The Sun was already geomagnetically pretty active at the time of launch, but a day after a minor geomagnetic storm erupted causing increased upper atmospheric drag at a critical point in the mission.

Every Starlink launch adds 49 car-sized satellites to low-Earth orbit in a temporary configuration before being boosted to a higher altitude. It is at that point that these satellites are most susceptible to changes in the upper atmosphere of our planet. The satellites sit between 210 and 240 kilometres above the Earth. Then, over several weeks, the onboard ion thrusters raise their elevation to 550 kilometres.

SpaceX has the wherewithal to talk to NASA scientists and astronomers regularly since the company is so well entrenched in its commercial relationship with the Agency and has access to the academic community. So why didn’t anyone check the space weather forecast? Considering the Sun is beginning to enter peak activity levels in its eleven-year cycle with the Solar Maximum expected by 2025, one would think this might be one of the pre-launch steps. But I guess the checklist didn’t include the weather forecast. The result will be about a $100 million hardware loss.

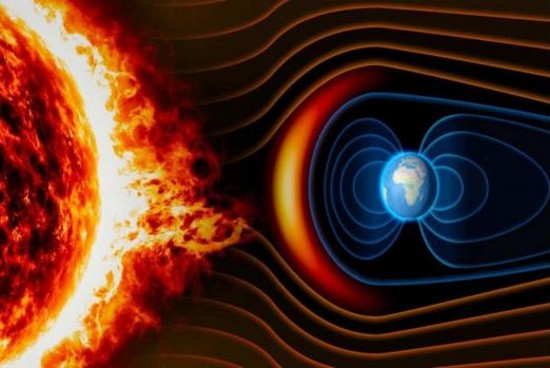

If you are unfamiliar with the term space weather, here’s a quick lesson. Weather without an atmosphere seems peculiar. But space has it and in our local area, the Solar System, the big contributor to the weather is the Sun. Although we are told space is a vacuum, it is compared to the best vacuum chambers we can create here on Earth. But yet it isn’t empty. In fact, it is filled with solar and cosmic particles, the detritus of comets, and lots of dust that rains down on Earth constantly. A solar sail, a contraption that looks like the sail you might raise on a boat, takes advantage of one aspect of space weather, the solar wind which provides a constant breeze of photon particles that can push a satellite along its way. And then there is the more active Sun that follows an eleven-year cycle which in peak periods can shed massive amounts of plasma and electromagnetic particles heading out from its heliosphere to bombard anything in its path.

The minor geomagnetic flare-up that happened last week seemed to catch SpaceX unaware even though the company had known about the probability of experiencing increased atmospheric drag from previous recent launches. A SpaceX report stated 50% increased drag in the low-200 kilometre target orbit. Considering that this geomagnetic storm was rated a 1 by NASA, a scale that goes between 1 and 5, what could happen to a constellation of satellites should a 5 occur? Would satellites at 550 kilometres be disrupted? Does this bode well for SpaceX’s Starlink and others who are already launching their own constellations like OneWeb?

A quick fix that will raise launch costs per mission by about 10% would be to raise the initial target orbit to between 300 and 350 kilometres in altitude. That has other challenges as well because the lower elevation made it easier to dispose of satellites that turned out to be duds. They would quickly fall back into the atmosphere like the 40 so far that appears to have been impacted by the geomagnetic storm. But at higher altitudes, any faulty satellites would take weeks if not months to fall back and burn up in the atmosphere.

So it would appear that SpaceX needs to be checking the weather in space, not just the weather at launch sites if it is to continue to launch at current rates of between 50 and 100 satellites per month. It’s not like there aren’t lots of eyes focused on space weather these days, so it shouldn’t be difficult to get up-to-date forecasts. Here are just a few that NASA lists on its website: the Advanced Composition Explorer, NOAA’s Deep Space Climate Observatory, the Sun-study satellites and Earth-based solar observatories run by NASA and ESA (the European Space Agency).

This article provides valuable insights into SpaceX’s weather report, highlighting the complexities of space travel.