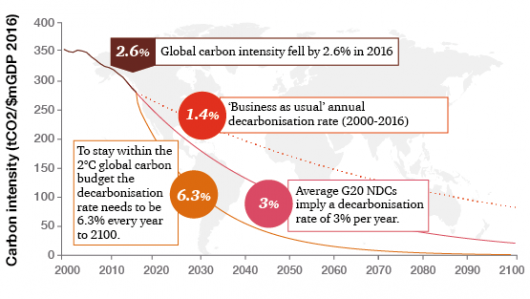

October 30, 2017 – In the latest Price Waterhouse Coopers (PwC) report looking at decarbonizing trends in G20 countries, carbon emissions per dollar of GDP fell in 2016 by 2.6%. This is consistent for the last three years and double the average since the year 2000. But as historically significant as this rate decline is, it doesn’t come close to meeting the objectives of the Paris Climate Agreement which calls for a 6.3% decarbonization rate per year to keep global mean temperatures from rising 2.0 Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) by mid-century.

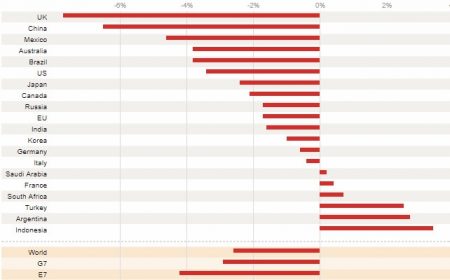

The countries ahead of the decarbonization curve include the United Kingdom, China, Mexico, and Australia. All grew their economies while reducing emissions. The first two implemented policies to drive down coal consumption. But coal demand actually increased in countries like Indonesia, India, and Turkey. So declines were offset and coal consumption fell by 1.4% in 2016. Gas and oil demand at the same time grew by 1.8%. Encouragingly, solar output increased by 30%, and wind by 15.9%, but these represented only a fraction of the energy consumed globally.

PwC projections see global economic growth averaging 2.1% over the next few years. For the nations of the world to limit global atmospheric heating to meet the upper end of the Paris target of 2.0 Celsius, it will require carbon emission across the planet to fall by 4% annually.

The graph below illustrates the current state of decarbonization and where we actually are trending versus where we need to go.

In the report, PwC predicts at current decarbonizing rates the carbon budget will run out by 2036. What does that mean?

The report states all of us need to brace for disruption because of physical risks, market and technology risks, and policy decisions by national governments.

What are the physical risks? Extreme weather events we see today are being linked to a warming atmosphere and ocean. Increased frequency and severity of extreme weather will require businesses to harden their infrastructure to withstand disruptions to supply chains and operations.

In terms of technology risks, decarbonizing our national economies is an experiment that requires technological innovation to help support the transition. We are already doing this with solar and wind power as a substitute for coal-fired power generation. We are seeking new energy storage innovations including better batteries. We are applying sensors and artificial intelligence to infrastructure in buildings, in heating and cooling systems, in transportation, and more, spawning what today is referred to as the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

And as for policy, the challenge remains for governments to implement low carbon solutions. There are many choices from carbon pricing to carbon currency, and from the setting of new standards and regulation.

Even investors and consumers are influencing business policy by challenging company boards of directors to disclose climate risk, and through purchasing power, favouring companies that show commitment to decarbonizing in products, packaging, and supply chain.

Want to know where your G20 country fits in the current index? Check out the graph below.

One industry that appears to be absent from the PwC’s analysis, is agriculture. The carbon contribution of this economic sector seems to be overlooked by many assessing the climate change file, a significant failure in oversight.

To read the full PwC current report go to the link provided here.