Every year I get my influenza vaccine. So does my wife. We do this because our daughter was born with heart disease and we want to ensure that we don’t give her an unneeded bout of the flu which could compromise her health. But every year those who make the flu vaccine or using a best guess approach in formulating the serum.

Flu is an interesting virus. What occurs in the Southern Hemisphere’s winter may be the flu we get in the winter that follows here in the Northern Hemisphere. And of course, vice versa. So you would think that our bio-pharmaceutical industry would have plenty of notice on how to formulate an effective vaccine.

But last winter they got it wrong and lots of people who had the vaccine also got the flu because the variant that hit here in North America was not the one the industry thought we would get.

That’s why I’m interested in how synthetic biology, that is the genetic engineering of vaccines, can allow pharmaceutical companies to speed up the process of developing vaccines in response to viral outbreaks. This means creating a synthetic virus with genes harvested during a disease outbreak and incorporated into an engineered organism.

The method has been tested in a drill in 2011 which mimicked a mock outbreak of an H7N9 outbreak, the bird flu. Novartis, the bio-pharmaceutical company started the test on a Monday morning and by Friday noon its scientists were growing and incubating live virus in cells in preparation to mass produce a vaccine. All done in less than five days.

How can synthetic biology help with other diseases and as a cure for seasonal illnesses? In May this year the Synthetic Biology Center at Massachusetts Institute of Technology held a workshop in which scientists and researchers discussed ways to use the technology in treating cancer, engineering tissues, curing diabetes and other metabolic diseases, drug screening and vaccinations for infectious diseases. You can check out their findings yourself in the session reports.

The goal of those working in this burgeoning field is to develop within the next decade kill switches to turn off metabolic disorders in patients, more personalized and individualized therapies, and of course quick responses to outbreaks of highly infectious and spreadable diseases.

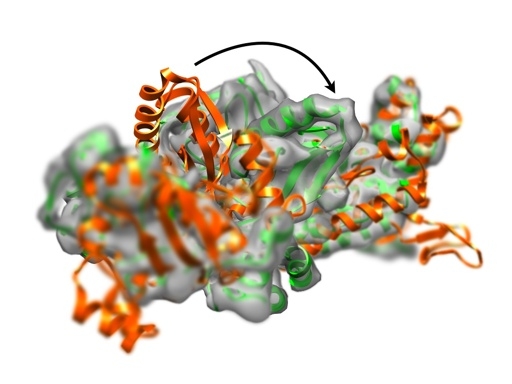

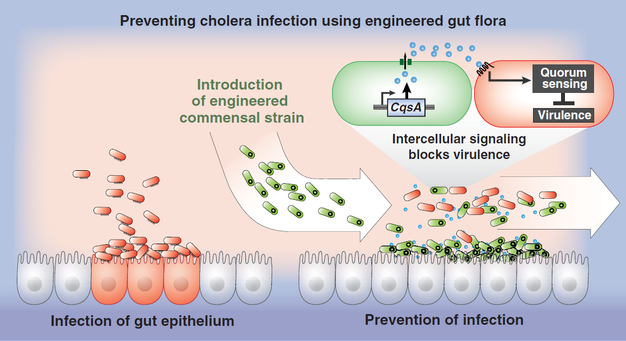

One commonly found disease in the Developing World is cholera. Can we stop it from infecting between 3 and 5 million and killing 120,000 every year? We know how cholera spreads – through contaminated food and water. We know how to create water filters to screen out most of the bacteria. But what if we could alter our bacterial flora in the gut to prevent Vibrio cholerae from causing the diarrhea and massive dehydration associated with the disease? At UCSF researchers are trying to do just that, preventing cholera infection in mice studies that use the E. coli virus as a mechanism for delivering new genetic material to gut bacteria. The altered bacteria blocks Vibrio cholerae from attacking the epithelial cell lining the bowel. The diagram below shows just how it works.

Expect to hear more about synthetic biology in future postings here.