July 20, 2019 – In Parts 1 and 2 of this series posted over the last two days I described four of the geoengineering ideas being bandied about in academia these days: solar radiation management by satellite, upper atmosphere aerosol release, direct carbon capture from the air, and seeding the oceans with iron sulfate. In this concluding part we look at:

- Stopping polar ice melt

- Green walls and reforestation

Stopping Polar Ice Melt

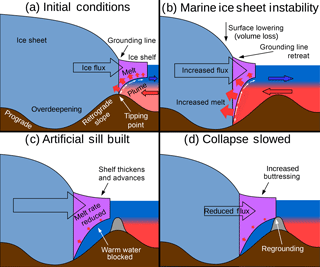

Like the boy who put his finger in the dike to stop a flood in the Dutch tale of old, scientists are coming up with their own versions for stopping the ice from melting in Antarctica. There are two current proposals. One suggests we build a massive wall under the Antarctic ice sheets to keep them frozen and in place for the next thousand years. The other suggests we make it snow a lot more in Antarctica to preserve the ice sheets. In both cases, the idea is to stop catastrophic sea-level rise over the next few centuries that would inundate large swaths of coastlines where most of humanity lives.

The wall idea would be a megaproject unlike any undertaken in human history. Described by its proposers as a “locally targeted intervention,” it would stabilize the outlets of specific ice streams flowing off Antarctica, blocking off the warming Southern Ocean from undermining ice shelves and the glaciers behind them.

Described as simple structures to prevent ice field erosion and melting, the targeted site would be between 80 and 100 kilometers (50 to 62 miles) in width, at the base of the Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica. This would be a test case that if successful would lead to other site builds. States Michael Wolovick, Department of Geosciences, Princeton University, “The most important result is that a meaningful ice sheet intervention is broadly within the order of magnitude of plausible human achievements … If [glacial geoengineering] works there then we would expect it to work on less challenging glaciers as well.”

In a second proposal described as stabilizing the West Antarctic Ice Sheet using mass surface deposition, researchers propose stabilizing two West Antarctica glaciers, the Pine Island and Thwaites. Both have recorded significant ice loss in the last two decades beginning with 6 Gigatons and growing to more than 40 Gigatons annually. What the researchers believe could work as a geoengineering experiment, would be the creation of massive amounts of artificial snow, dumping it on both glacier surfaces to stabilize them.

The idea would be to add up to 10 meters (32 feet) of surface ice to the glaciers annually over the course of a decade by manufacturing snow in the same way ski resorts do today, but on orders of magnitude much greater than anything ever done. The amount of ice that would be added equals 7,400 gigatons. A gigaton is a billion tons.

The researchers conceive of the building of pumps to bring up ocean water some 640 meters (2,100 feet) in elevation, desalinating it and then using snowmaking equipment to spray it over the ice sheets. Power would come from 12,000 climate-hardy wind turbines.

The price tag of both of these ice saving schemes isn’t even accounted for in the proposals. And as geoengineering schemes go, one could compare them to Manhattan Projects in their scope, requiring international agreement. Neither proposal talks about unintended consequences of implementation, or of failure, other than to point out doing nothing would lead to many of our coastal cities being inundated over the next few centuries.

Green Walls, Reforestation, and Afforestation

In China and Africa, tree planting on a colossal scale is underway to alter the climate of vast areas of land.

The new Chinese Great Wall has been on the go since 1978 with 66 billion trees planted so far. The project is planned to continue until 2050 when it will stretch some 4,500 kilometers (2,800 miles) across the northern parts of China and covering 405 million hectares (more than 1 billion acres) increasing the world’s forest coverage by more than 10%. What started as a way to block the expansion of the Gobi Desert, is now seen as a carbon reduction project with the hope that the majority of trees planted can survive and grow. If they don’t then the dying will further contribute to global warming.

The African Green Wall is a project crossing 11 countries along the southern boundary where the Sahara Desert meets the Sahel. Launched in 2004 the project involves the planting of drought-hardy native trees over a 7,000 kilometer (approximately 4,350 mile) stretch, to a depth of 15 kilometers (9.3 miles), to keep the Sahara at bay, and alter local climates to allow for sustainable agriculture and the harvesting of the produce created by the trees. The native species being grown include Acacia, Jujube, and Desert Date trees.

The jury is out on whether either Green Wall will achieve the purpose for which they are intended.

Recently, Thomas Crowther, an Assistant Professor of Environmental Systems Science, ETH Zurich, a Swiss science and technology university, spoke about a way to remove carbon from the atmosphere in volumes greater than the human-produced emissions our modern industrial world produces. He argued that the most effective way for us to address climate change was through biogeochemical cycling, the planting of 1.2 trillion trees in the world’s parks, forests, and abandoned wasteland. Crowther considers trees to be the “most powerful weapon in the fight against climate change.” Planting 1.2 trillion would remove the equal of carbon emissions produced over a decade based on present output. Crowther has identified more than a million sites around the world where afforestation and new planting could help to achieve his targeted number.

There is no doubt that tree planting represents a natural geoengineering tool to combat climate change. But questions remain. If you plant trees in areas where they cannot sustain themselves, cannot grow to maturity, then the long-term carbon sequestration capacity of such growth is questionable. Massive tree die-offs contribute to atmospheric emissions. And planting trees that are not suitable to the environments in which we are attempting to grow them is a recipe for climate disaster.

Currently, the United Nations has launched a trillion tree campaign. And the continent other than Africa most vulnerable to climate change, Australia, is planting trees with a target of 1 billion by 2050. The goal is to remove 18 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, 3.6% of Australia’s present annual CO2 emissions.