September 22, 2017 – The fear and uncertainty spread by those who feel that genetically modified anything is bad needs to be weighed against mosquito spread infections that are defying normal medical intervention.

A new resistant Plasmodium falciparum, first detected in Western Cambodia in 2008, has now spread to the Greater Mekong Valley posing a growing threat to the lives of millions. The details are to be published in the October 2017 edition of the Lancet in an article entitled, “Spread of a single multidrug-resistant malaria parasite lineage to Vietnam.”

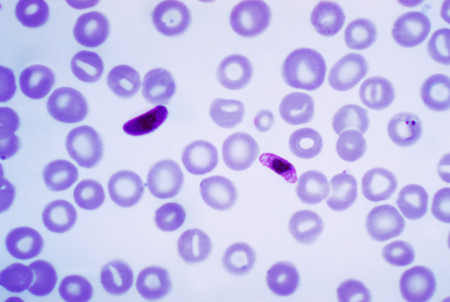

Plasmodium falciparum is the parasite responsible for malaria. The normal treatment involves two drugs, artemisinin, and piperaquine. But the parasite is now showing significantly increased resistance to both drugs and outbreaks are spreading into Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam. In parts of Cambodia, the treatment failure rate is close to 60%. Tropical disease experts fear this is only the beginning and that Africa is next. Why is that an even greater concern? Because the largest number of malaria cases are in Sub-Saharan Africa, and that’s where 92% of malaria deaths occur.

Tropical disease experts fear that Africa will be the next destination of this “super malaria.” Why is this significant? Because malaria is prevalent in Africa more than anywhere else on the planet. In fact, 92% of malaria deaths each year happen in sub-Saharan Africa. According to the World Health Organization more than Africa and Southeast Asia are at risk. Half the world’s population today lives in areas defined as malaria zones.

Fighting malaria until this latest “super malaria” appeared seems to have been largely successful. Aggressive prevention involving the distribution of mosquito netting for beds, putting screens on windows and doors, and the rigorous spraying of mosquito breeding grounds, have reduced mortality rates by 29% between 2010 and 2015. Even with these efforts, however, 429,000 deaths from malaria were recorded in 2015, with 303,000 of them happening to children under the age of five. That’s one child death for every two minutes in that year.

The head of the Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit located in Bangkok, Professor Arjen Dondorp, told the BBC News, “I’m quite worried…Around 700,000 people a year die from drug-resistant infections, including malaria…If nothing is done, this could increase to millions of people every year by 2050.”

But there are two things that can be done. The first is re-engineering the mosquitoes that are the carriers to eliminate them. The second is developing a vaccine to immunize people to malaria.

GMO Mosquitoes

I described genetically engineered mosquitoes back in 2012 as a genie that needs to be let out of the bottle. The genie is gene drive technology, using tools such as CRISPR/Cas9, was being used to modify mosquitoes in an effort to combat dengue fever and malaria. A British company, Oxitec, developed these genetically altered mosquitoes to interbreed with wild populations and kill off the offspring before it became a flying carrier of infection. Described as self-limiting because the program is designed to inhibit reproduction, meaning both the wild and GMO versions of the insect end up dying, this technology appears ideal for eliminating the carriers of the new resistant Plasmodium falciparum parasite.

Malaria Vaccine

In another medical advance that may provide a means of immunizing people against contracting “super malaria,” the first public distribution of a vaccine, Mosquirix, is being trialed in three African countries in 2018. Although this vaccine may not be the immediate answer to this new Plasmodium strain, it represents a promising advance that could ultimately lead to a permanent immunization program.

Will we finally be rid of malaria by 2050 or will Professor Dondorp’s fears be realized? The former is within our grasp with the technologies we have created. What’s needed is a little bit of capital and a dose of political will to accept GMO and end this human scourge once and for all.