February 23, 2014 – We lost the WiFi connection yesterday and hence no postings appeared. Instead I read by the pool seeking additional information on the issue of construction materials and carbon. I also got in quite a bit of swimming.

What I discovered is two technologies that can decrease the impact of concrete as a principal component in building materials. One of these is eminently suitable for use in many parts of the Developing World where there is limited access to energy and a lack of industrial infrastructure. The second comes from countries which benefit from high levels of volcanic activity.

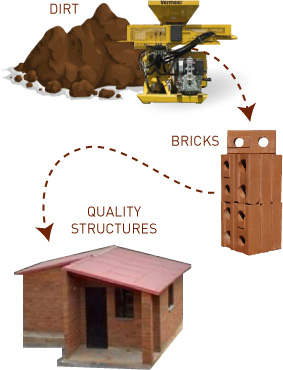

“Dirt” Cheap Building Blocks

A Dutch-based corporation that is known more for its menagerie of industrial equipment, Vermeer Corporation, a few years ago developed the Vermeer BP714, a compressed-block-from-earth machine. In 2013, Popular Science, named the technology one of the 100 most remarkable innovations of the year. Today, through a unique marketing arrangement, Dwell Earth, an Iowa company, is distributing and educating many in the Developing World about the merits of building with these very green-friendly compressed earth blocks (CEBs).

What makes the technology so attractive? The construction material is soil mixed with a tiny amount by percentage of Portland cement. The soil and cement are put in a hopper and fed to a hydraulic press exerting 25,000 kilograms (55,000 pounds) of pressure. The press is powered by an internal diesel engine. The BP714 spits out building blocks at the rate of one per 15 seconds. Each compressed earth block measures approximately 17 x 35 x 10 centimeters (7 x 14 x 4 inches). The blocks need 7 days to cure before using them for building. At 28 days they are fully cured and water resistant. The bricks absorb and release heat more slowly than traditional concrete block or fired bricks. The result, houses built with compressed earth block stay cooler during the day and warmer overnight.

Consider this. Today 2 billion humans, 30% of our global population, live in accommodations built from earth. Earth has been a primary construction material in homes for thousands of years. The material is found literally right beneath our feet so there are no transportation costs. And earth-built structures can last for centuries unlike wooden ones.

Are there any disadvantages to structures built with CEBs? They are heavy and as a result free-standing unreinforced structures are limited to no more than 2-storeys in height. Can they withstand an earthquake? If reinforced with re-bar CEB-constructed buildings can withstand the shaking of a seismic event. The blocks are designed for the integration of steel caging just as is the case with regular concrete block.

How does the cost compare to building using fired brick, standard concrete block and poured cement? According to Dwell Earth, the savings over these traditional construction materials is about 30%. One would think the cost should be even lower but maybe as the technology becomes more widely distributed savings will exceed 30%.

How are CEBs greener than standard concrete block? Their production uses significantly less energy, and the heatless process itself means far less CO2 enters the atmosphere.

Iceland and the Philippines Experiment with Volcanic Ash Cement

Are volcanic eruptions good for anything? Well according to those in the know in Iceland and the Philippines volcanic ash is suitable as a material for use in the making of concrete. This practice dates back to classical antiquity when the Romans mixed ash with lime in cement. Roman cement structures are among the most durable ever built by humans and maybe volcanic ash is one of the reasons.

In Iceland, post the eruption of the volcano, Eyjafjallajökull, the ash that disrupted air traffic over Europe is being put to good use by the Icelandic Innovation Centre to make a marketable cement-free concrete that produces no CO2. The volumes of ash from the foot of Eyjafjallajökull are in sufficient volume to spawn an entirely new industry. Initial results are very promising with full production expected to be ready within the next two years.

In the Philippines, ash from the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991 is being used for both road and building materials, mixing it with asphalt in the former, and in concrete for the latter. The eruption produced between 5 and 8 billion cubic meters of ash giving the country an enormous resource with which to experiment. The use of ash is producing a very green and reliable building material. Considering the continual threat of volcanic eruptions on the islands it provides the country with a means to offset its human carbon footprint. Of course, it cannot do anything about the amount of greenhouse gases created by erupting volcanoes.

If you, my many readers, know of other green building infrastructure technologies that you feel we should be discussing please let me know in your comments.

Len Rosen