You can’t just grow potatoes on Mars despite what we read in The Martian, a science fiction novel by Andy Weir, published in 2011, and brought to the big screen in 2015 starring Mat Damon. Marooned on Mars when he is presumed lost by his crew, with a background in botany, this astronaut turns his habitat into a farm. He uses stored waste left on Mars to fertilize the soil, water from the extraction technology brought to Mars for the mission, and a store of potatoes to plant and grow enough food to keep himself alive. That, and a lot of ketchup.

Growing Earth plants on Mars presents many challenges. For plants to thrive they need adequate sunlight for photosynthesis, a growing medium (Martian soil has high concentrations of perchlorate salts that present a challenge), and lots of water. Even if we genetically modify these plants to become tolerant to less light and drought resistant, the conditions to produce adequate yields to feed humans planning for long-term stays on the planet remain problematic.

A recently published book, Dinner on Mars, describes the agricultural challenges. Co-authored by Lenore Newman, Canada Research Chair for Food Security at the University of the Fraser Valley in British Columbia, and Evan Fraser, Director of the Arrell Food Institute at the University of Guelph in Ontario, these two ask the question “Can we feed a city on Mars?” It’s a legitimate query considering that Elon Musk and SpaceX have a mission to do just that. What is so interesting about Dinner on Mars, is that in solving the challenges to feed Martians, the authors believe it will change how we grow our food here on Earth.

Water on Mars can be found just below the surface of the regolith. It is frozen. There’s not a lot of it but enough for the right kind of plants to grow. The regolith, however, is toxic (the perchlorate issue), sandy and lacking organic content. The authors propose introducing cyanobacteria which on Earth is found in polluted water. Cyanobacteria is blue-green algae, hence its name. On Mars the bacteria would harvest carbon dioxide (CO2) from the thin atmosphere and tackle the perchlorate in the soil, neutralizing its toxicity. At the same time, the cyanobacteria would produce the missing organic matter needed to support other plant life.

On Mars, some plants would be grown in Martian soil while others would be supported by hydroponics in greenhouses. The vertical farming that is increasingly being done here on Earth in cities will find its element on Mars. The authors believe Martian cities will be filled with plants being grown everywhere and will include salad greens, vegetables, fruit, herbs, coffee and even chocolate. Grains will not take priority because of limited space. And the plants will give back to the human inhabitants by providing oxygen, organic materials for manufacturing, and water filtering and recycling.

What you won’t see on Mars is livestock. No cows, pigs, sheep, goats or chickens. Instead cultivated protein from stem cells will create lab-grown equivalents. Precision fermentation using food waste as the medium combined with yeast, fungi and bacteria will produce the rest of the protein that on Earth is derived from eating meat and soy products like tofu.

Food grown on Mars will need to account for every gram of organic matter added, every millilitre of water, and every photon of light (the maximum amount of light on Mars corresponds in energy to 590 Watts per square metre versus 1,370 here on Earth). With the latter, the use of greenhouse LED lighting will be necessary. And if solar energy is used to power these lights, the size of the arrays will have to be much larger or the panel conversion efficiency will need to be that much greater than the average here on Earth.

One thing the authors of Dinner on Mars don’t talk about in the book is pollinators. On Earth, flies and beetles have been pollinating plants for hundreds of millions of years. Today, farms rely on bees to pollinate fruit and vegetable crops. But can bees survive on Mars? A 2019 article in Wired bore the following headline, “Bees, Please: Stop Dying in Your Martian Simulator.” In enclosed habitats designed to simulate the environments of the Moon and Mars, bee deaths were significant amounting to 1,000 to 1,200 every four days and instead of seeking sources of nectar and pollen, the hive inhabitants exhibited wintering behaviour, reducing activity to survive.

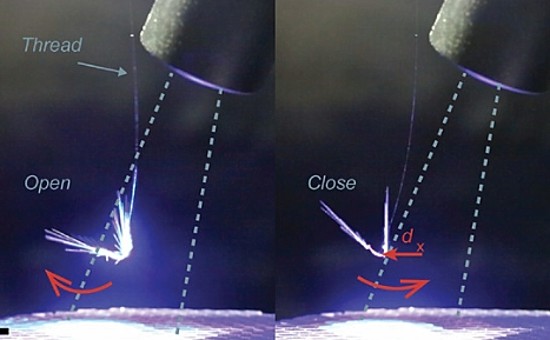

If we can’t bring the bees to Mars, then maybe we can invent a robot pollinator. That’s exactly what researchers at Tampere University in Finland have done. They have built a flying robot that responds to light and resembles a dandelion seed. It weighs 1.2 milligrams versus adult honeybees at 120 milligrams. The robot pollinator (seen below) can be powered by a light source such as a laser or LED. Something like this could be further designed to specifically take advantage of Martian conditions making the need for honeybees redundant. The only downside, with no bees there will be no honey to sweeten Martian meals. You can read about the robot pollinator in the journal of Advanced Science in an article published on December 27, 2022.