October 25, 2014 – When the Deepwater Horizon blew up in the Gulf of Mexico some scientists speculated that it was inadvertent contact with frozen methane that precipitated the disaster. British Petroleum was drilling in an area of the Gulf known for methane hydrate formations and there were signs that hydrates were forming within the drill rig apparatus itself. The Gulf of Mexico Hydrates Research Consortium, an organization formed by oil and gas exploration companies, shortly after the Deepwater Horizon disaster, sent a research vessel to the area to collect marine sediments. Methane hydrates were found to be in abundance. In one experiment a bubble stream of methane being emitted from the seafloor about 16 kilometers (10 miles) from the site of the Deepwater Horizon was captured in a tube where it immediately reformed as methane hydrate.

Japan has also been experimenting on methane hydrates in an area of the Pacific south of Tokyo. In March of last year I described that country’s successful attempt to harvest natural gas from these icy formations. Now joining Japan is The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin) which has received funding amounting to $58 million U.S. to analyze methane hydrates in the Gulf of Mexico. Joining the study are researchers from The Ohio State University, Columbia University, the Consortium for Ocean Leadership and the U.S. Geological Survey.

The Gulf of Mexico is estimated to contain 7,000 trillion cubic feet of methane trapped near the seafloor surface. That number is 250 times greater than the total amount of natural gas burned by Americans in 2013.

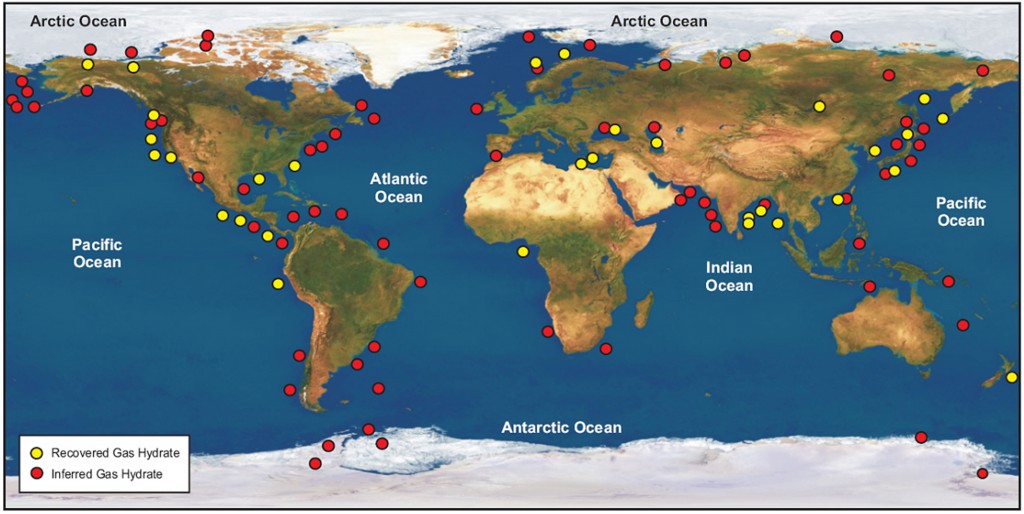

The map below shows known and inferred locations for methane hydrate around the world. Produced by the Council of Canadian Academies in 2008 it is interesting to note that methane hydrate formations trapped in permafrost in the Northwest Territories of Canada are not indicated. Lots of other sites around the world are displayed. So there is a lot of methane hydrate to be found but there is a caveat. This frozen ice-gas mixture only remains stable under high pressure and low temperatures. Depressurize it or warm it and you have an explosion on your hands.

So what will UT Austin do with the $58 million it received? A four-year study to acquire intact core samples of methane hydrate which will be brought to the surface. The technological challenges include keeping the methane hydrate frozen and pressurized during the ascent.

Some describe the project as being equivalent to the initial studies of shale gas and oil some three decades ago. At that time no one suspected that hydraulic fracturing (fracking) technology would free up tightly bonded rock formations containing fossil fuels. Today fracking is producing an oil and natural gas boom in the United States but remains controversial for many reasons including contributing to polluted aquifers and methane release exacerbating global greenhouse gas emissions.

Methane hydrates may prove to be just as controversial, a genie when led out of its high pressured, frozen bottle, that furthers our dependency on fossil fuels, defeats our attempts to mitigate the causes of climate change, and creates disasters akin to Deepwater Horizon. See what $58 million can buy you!