January 6, 2014 – Among the great rivers of North America, the Colorado is the one most threatened by climate change. The river runs from the Rockies to Arizona, southern California and Mexico. Today its many dams and reservoirs contain less than half the water capacity they were designed to hold. And this is only the beginning of what climatologists are predicting will be drier periods ahead.

Lake Mead, the man-made water source seen below, a crucial water resource for both Las Vegas and Los Angeles, is showing a giant bathtub ring along its shoreline, made from white mineral deposits as the water level drops. This is threatening 70% of the people in Nevada who may lose their primary freshwater source.

The American Meteorological Society has released a study in preliminary format entitled, Understanding Uncertainties in Future Colorado River Streamflow. It describes the importance of the river as a freshwater source to more than 30 million Americans and Mexicans, and provides evidence from climate models that predict a decrease between 10 and 45% in river volume by 2050. The variability in the models occurs because GHG emission levels may not escalate to 450 ppm during the time frame indicated, and climate models vary in predicting the impact of elevation on precipitation, snow pack, runoff and temperature. But one thing is consistent throughout all the models – a decline in freshwater river volume with the greatest risk a multi-decadal drought, something the basin is currently experiencing with no end in sight.

A summary of the Colorado’s future includes the following:

- rising temperatures from south to north.

- declining precipitation greater in the south than in the north.

- reduced runoff from snow pack and mountain sources.

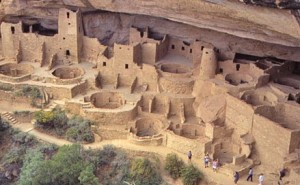

What is projected to happen to the Colorado is consistent with climate models for much if not all the U.S. Southwest from Texas to California and as far north as Oregon, Wyoming and Colorado. The Colorado has experienced droughts in the past. The most recent occurred in the 1930s and 1950s. In addition there is plenty of paleoclimate evidence to show that drought in the U.S. Southwest may have played a significant role in the decline of the Anasazi civilization with its cliff abode cities.

What does this mean for planning? For the many cities that rely on the river as a freshwater source and for the farms that draw upon it for irrigation it means implementing significant water conservation policies, developing grey water strategies to recycle and reuse water many times, and finding drought tolerant alternatives to existing crops so that farming can continue. This will stretch the resource and ensure every drop coming from the Colorado is not wasted.

A postscript having nothing to do with the Colorado River: A hiatus in postings occurred last weekend, consequences of Toronto’s recent ice storm and following deep freeze. A water pipe to the outside wall of our apartment cracked open and flooded us out. I was able to save my computer although it did get wet. A few days of drying and the application of a hair dryer seems to have done the trick and we’re back blogging. Our floor is a goner and will have to be replaced. And of course there is a gaping hole in our vestibule wall. But those damages can be fixed. I would have been pretty bummed out if I had lost the computer even though I backup regularly.

– Len Rosen

Sorry to hear about your water damage.

Is it time for (more?) desalination plants on the Wagner Basin? Just so it’s funded privately or by issuing government bonds from Arizona, California, and Mexico. I don’t know the geography, would it be feasible to bring water to the Southwest corner of Arizona?

Hi Harlan, It is technically feasible to pipe water anywhere within reason. The question really is “do the economics work?” A gallon of water delivered this way not including cost of production through desalinization, I believe, would bear a pretty significant price. I would bet more than a gallon of gasoline.