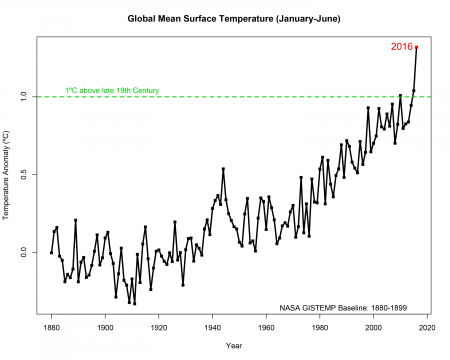

July 24, 2016 – It’s getting a bit mind-numbing to read these days that the latest month is statistically the hottest the world has ever recorded. NASA and NOAA scientists just told us in the last few days that the first half of 2016 was exceptionally warm. Their mid-year analysis states that we have set the modern record for warm temperatures in 2016 based on satellite and sensor readings from around the planet. Average global temperatures exceeded those recorded in the late 19th century (when we first started keeping comprehensive climate records) by 1.3 Celsius (2.4 Fahrenheit) degrees.

For the Arctic the global mean rise is nothing compared to the kinds of temperatures being witnessed above the Arctic Circle. Walt Meier, a NASA Goddard sea ice scientist states, “It has been a record year so far for global temperatures, but the record high temperatures in the Arctic over the past six months have been even more extreme.” Meier is part of Operation IceBridge, a NASA mission to map the melt appearing on sea ice where ponds form in the early summer and act as an excellent predictor of the extent of the total sea ice mass minimum will be by September.

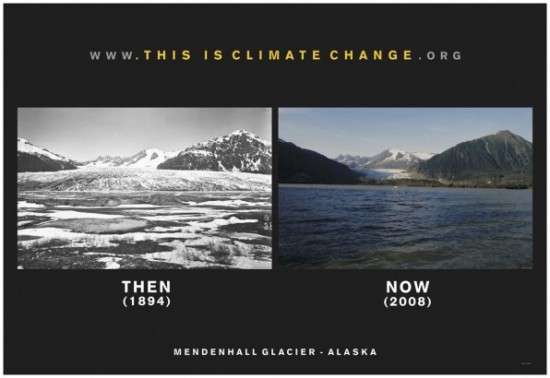

In Alaska visitors to the Mendenhall Glacier, near the state’s capital city, Juneau, bear witness to just how much rising Arctic temperatures are impacting land ice. Back in 1979 my wife and I took an Alaska cruise from Vancouver and one of our stops was Juneau and a visit to the Mendenhall. When I looked at the pictures we took back then and the images available of the glacier today I was amazed at just how much had changed. But even more dramatic are views of the Mendenhall taken back in 1894 versus more contemporary images from 2008. You can see the change in the image below.

An ice dam in the lake that forms in front of the Mendenhall Glacier just a few days ago broke aided by the increasing volume of meltwater. Hiking paths to the retreating face of the glacier were inundated.

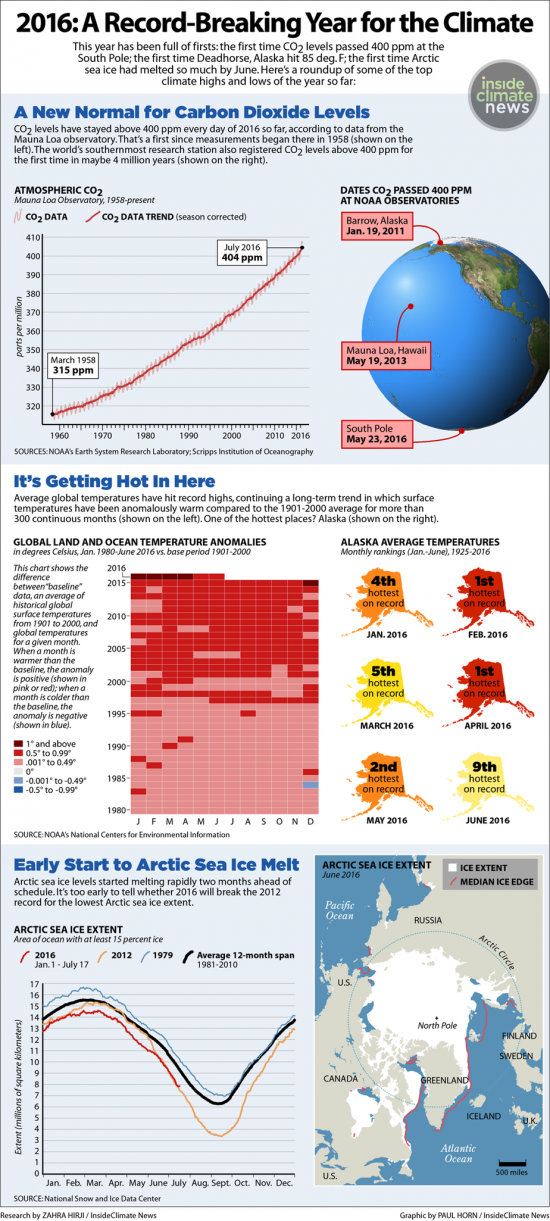

For Alaska, the U.S. Arctic outpost where NASA and NOAA scientists do much of their on ground and ice research, they note that these last six months are the warmest since records began in 1925. Deadhorse, Alaska, located close to the shore of Prudhoe Bay, on the North Slope Arctic coast, reached 29.5 Celsius (85 Fahrenheit) degrees on July 7. I share with you an infographic that provides some pretty compelling data about the extent of climate change being observed.

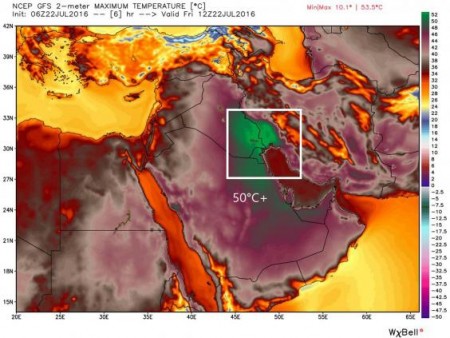

The poles aren’t the only areas of the planet feeling the heat. In the last week a weather station in Kuwait recorded a daytime temperature of 54 Celsius (129.3 Fahrenheit). Iraq, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia all saw temperatures exceeding 50 Celsius (122 Fahrenheit). The areas highlighted in green on the amp below are those experiencing what would be considered unlivable outside conditions for most humans.

What does this trend to ever increasing warmth mean for the human condition? Researchers estimate that rising temperatures could cost the global economy over $2 trillion US annually by 2030. United Nations research indicates that 43 countries are most at risk to seeing a decline in their gross domestic product (GDP) from 1 – 6% annually. Heat stress will impact China, Indonesia and much of the remainder of South Asia making it too hot to work.

In an episode of Amazing Race Canada aired two weeks ago, teams were asked to perform tasks in daytime heat combined with humidity that produced a humidex close to 50 Celsius. It was painful to watch contestants suffering in the extreme hot weather. The Canadian contestants were brief visitors to the area but for those living there the ability to work has dropped in terms of working capacity by 15 – 20% in recent years. According to a study by Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health released in the last few weeks it predicts that work capacity will decrease even further by more than double in the year 2050. States Tord Kjellstrom, of the Health and Environment International Trust, Nelson, New Zealand, “with heat stress, you cannot keep up the same intensity of work, and we’ll see reduced speed of work and more in labor-intensive industries.” Will the impact be equally felt across the globe? According to Kjellstrom, no because “rich countries have the financial resources to adapt to climate change.”

A final note about the impact climate change is having in some of the more remote parts of our planet. The example is the Pamir Mountains of Central Asia, straddling Afghanistan, China and Kyrgyzstan. There climate change is altering the annual time cycles that human communities have relied on for centuries to understand when to plant, when to move herds, and when to harvest. Karfim-Aly Kassam, of Cornell University has headed up a team of researchers working with local residents to recalibrate time. They call the project the Ecological Calendar and Climate Adaptation tool or ECCAP. The hope is the results will help communities to better plan and adapt to climate change.

What has been happening in the Pamir? The inhabitants have seen a rise in glacial melt, more rain than snow, greater precipitation intensity and periodicity, disruptive river flow changes, landslides, lake bursts, flooding and rising temperatures. States Anthony Aveni, anthropologist and astronomer, from Colgate University, for these people “time is the environment.” Adapting to a disruptively altered climate calendar, therefore, is a matter of life and death.

Traditionally the Pamir communities have relied on 17 different local calendars for making decisions. These calendars don’t follow a January to December timeline. Instead days get counted from early spring and are plotted on a human body, a local leader known as a hisobdon who tracks the daily changes from toe to the heart and back again marking the seasonal cycles and normal annual milestones. Today hisobdon are in turmoil because planting is becoming a hit and miss proposition varying as much as by 15 to 30 days from just two decades ago. Wheat can now be sown at higher elevations on land never before used for agricultural purposes. Using these marginal lands means communities face an unknown whether they will succeed or fail from one planting to another. The ECCAP project, it is hoped, will add science to traditional Pamir practices and local knowledge. States Kassam, using the science of climate change means people will “be able to match their traditional practices in agriculture and grazing to a rapidly changing climate and thrive in the places that they have lived for generations.”