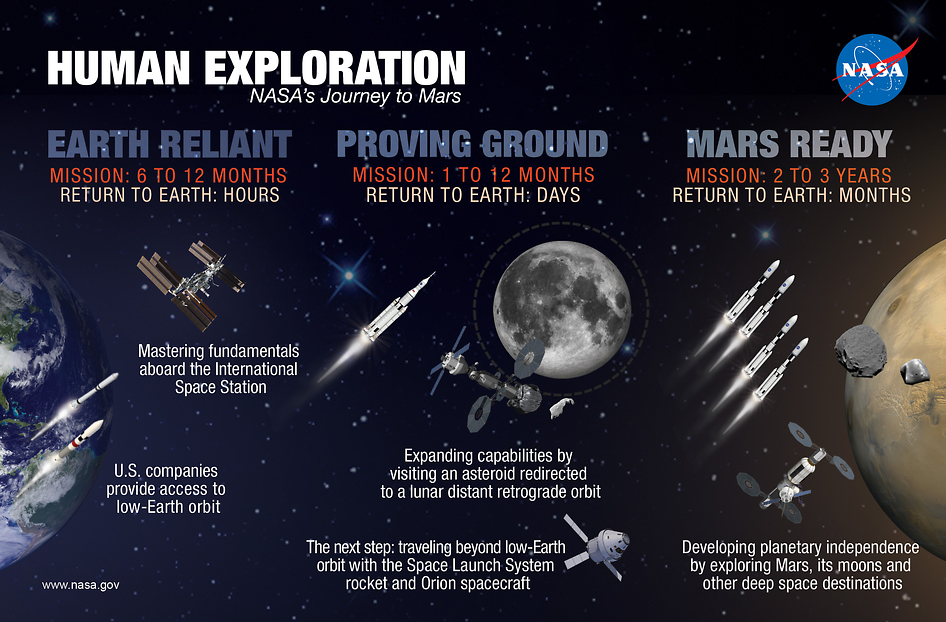

October 15, 2014 – I have written several postings about Mars One and have questioned the aggressive timetable and lack of appropriate tested technology to ensure its ambitious goal – to place the first human colonists on Mars in 2024. That’s fully a decade ahead of NASA’s own timetable to send a human crew to Mars to explore, not settle the planet. An infographic of NASA’s timelines appears below.

In my review of Mars One I have been a skeptic, questioning everything from the one-way journey, to the existence of proven technology to land the necessary equipment let alone human payloads on the surface, to the living accommodations and closed life-support infrastructure to maintain humans upon arrival, and to the long-term outlook for survival. In all these areas I have found Mars One to be wanting. And I’m not the only one. Students at Massachusetts Institute of Technology just published An independent Assessment of the Technical Feasibility of the Mars One Mission Plan. The author lead is Sydney Do, a doctoral student in aeronautics and astronautics. He and his four associates developed a simulation using state-of-the-art technologies and advances anticipated within the timetable Mars One has published. Their conclusion – a not very pretty ending for the first Mars’ colonists.

The MIT simulation reveals a number of crucial shortcomings in the Mars One plan including:

- A lack of state-of-the-art technologies to provide for In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU). Mars One is counting on having reliable technology capable of using local materials and resources from the planet surface and atmosphere to provide for shelter, water, oxygen and other life support essentials. As I have previously described in postings, these technologies have yet to be developed and scaled to meet life-support systems requirements for a project as ambitious as Mars One. For example, NASA’s next Mars rover will be the first mission with an oxygen generator on board. This is essential technology for future human missions and 2020 will be the first test of it. In 2014 we are just starting small scale production of a few food crops on the International Space Station. With Mars One the colonists, based on current plans, will be wholly reliant on locally grown foods. Simulating the Martian environment where the amount of sunlight available to plants is a fraction of that here on Earth, and where gravity conditions are different as well, has yet to be done. Will we need to genetically alter terrestrial plants to adapt them to Martian conditions? Or will we build an artificially lit environment for produce grown on the planet? And these are just two of the many ISRU technologies we need to evaluate and test before we can reliably assure a sustainable environment for human life on the planet surface.

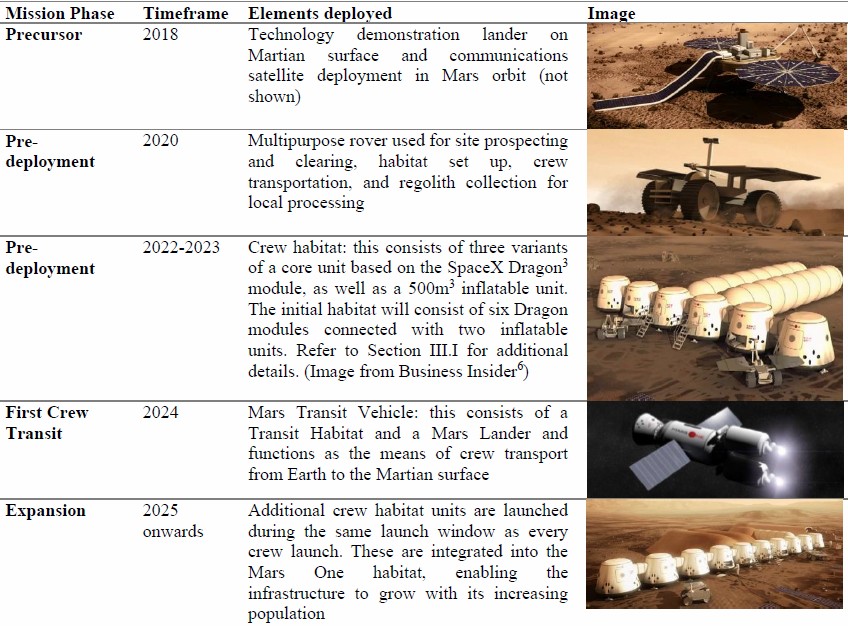

- The timetable for Mars One is aggressive and ambitious. And considering past mission failures to Mars could be disrupted by any one failure in the chain of planned mission steps. If you are not familiar with the plan a summary follows. The first mission launch is 2018. A lander with test-bed demonstration technologies for sustaining human life arrives on the planet. There is no guarantee that all the test technologies will work. Does this mean a second mission with new equipment will be required? There is no provision for this in the plan. Along with the lander a Mars One communication satellite will be placed in orbit above the planet for future mission support. Now the plan gets to its next stage. A rover in 2020 lands and begins searching for a settlement site. The Mars One team have chosen 45 degrees north latitude as the most likely area for search. What if the rover doesn’t find a suitable site? Does this mean a second or third rover mission to scout other likely sites? If the rover does find a suitable site it is equipped to prepare the site for future mission arrivals. I’m not sure what that means? Is the rover going to clear the surface of any obstructions that might impede the landing of future missions? Or will the rover be equipped to do extraction of vital materials needed for future missions? Those subsequent missions will deliver a range of habitation modules including inflatable living, life support and cargo units. The Mars One plans includes redundancy of units to ensure survivability. That’s a lot of cargo to put on the planet surface in a tight timetable that starts in 2022 and ends in 2023. Certainly more than one robotic device will be delivered to the planet surface to prepare the site for its first human occupiers arriving in 2025. One assumes redundancy will be a requirement for robots as well. After the first humans arrive Mars One will continue to launch and deliver habitation modules which will be prepared by the colonists and accompanying robots for the next phase in the growth of the colony. Mars One boldly states in its plan that “no new major developments or inventions are needed to make the mission plan a reality.” A reality check differs with this statement. Much of what is described in the plan is technology yet to be built.

- To ensure survival of humans landing on Mars in 2025 the Mars One plan contains a number of habitat failure conditions that experience with closed-loop life support system tests here on Earth expose. These include: crew starvation because the colony fails to produce enough food; crew dehydration because the in-situ technology cannot produce the amount of freshwater needed for both humans and food crops; crew hypoxia brought on by the failure to produce an adequate amount of oxygen, crew CO2 poisoning because of the failure of habitation systems to manage buildup of the gas, fire risk from a buildup of oxygen exceeding 30% in crew habitats, and habitat depressurization leading to crew disorientation and death. The current Mars One plan states that its life support units are “very similar to those…fully functional on-board the International Space Station.” But the ISS systems are designed for near-Earth orbit and work in micro-gravity conditions. That’s not the same as the environment of Mars and, therefore, one shouldn’t assume the same results. They make work better or worse.

In the MIT report’s conclusions Mars One fails to meet conditions that would ensure those who are selected to go will have any chance of surviving over the long term. The lack of tested technology components required for sustaining life remain a significant impediment. The lack of sufficient understanding of closed-life support and experience with self-sustaining crop production technology will expose the colonists to extreme risks. And the logistics of the entire project understate the launch requirements, resupply needs and required redundancies necessary to ensure human survival. In other words, Mars One as staged and planned (see below), will be a reality show with a horrifying ending as the human colonists fail to survive.

Humans have no business trying to transport their frail physical bodies to the hostile surface of Mars. One could envision affordable rational schemes where smart robots build rotating artificial gravity wheel ships/habitats to transport human bodies from Earth to Mars orbit, and the humans could live in the orbiting wheel ships while they are radio-link mind-melded with robots roaming the Martian surface. The long com-link times imposed by the universal speed-of-light limit prohibit real-time mind meld with robots on Mars with humans on Earth. So, if humans want to explore Mars in real time, they must shorten the mind-meld com-link time to the short interval between the Mar’s surface and Mars orbit (maybe only ¼ second round turn). There is no point in putting humans into Mars orbit until their robotic mind-meld companions are already roaming the surface. Mankind needs to put smart robots on the moon, and mind-meld with them while staying comfortably on Earth (only a couple-second com-link delay to the moon and back. Mankind needs to do that, and perfect the technology, before it attempts real-time exploration of Mars. We are talking about a nearest reasonable manned Mars mission time line of ~ 2035.

But I don’t see that happening. If the robots are not at least as smart as humans, the humans won’t have the technical means to safely go. But if the robots are as smart as we are, we won’t have any good reason to go. The robots will go, send back all the data needed to create a precisely accurate and very fine-grained virtual reality of Mars, and all the humans on Earth would be able to mind-meld with virtual robots roaming the virtual surface of Mars. I’m guessing most humans would quickly tire of roaming an airless, dusty, lifeless, and lethal radiation bathed virtual reality lifeless Martian desert, and opt for one of countless other much more engaging virtual realities.

Cocktail party chatter in 2035 about virtual-reality Mars:

“Frank, have you been to Mars yet”?

“Yeah, Bernard, my wife went and only stayed ten minutes. She said it was a total waste of time. But my wife has a limited attention span, no scientific curiosity, and even on her best day has an AI augmented IQ of only 170. So I figured if she didn’t enjoy it, I probably would. So I went. My wife isn’t often right about very much. But I must admit she got Mars about right. I stayed 12-minutes just to prove I’m at least as smart as my wife. If you would like to be bored out of your gourd, be sure to take an actual-data virtual-reality robotic mind-meld trip to virtual Mars.