It looks like 2023 will be the year that mean atmospheric temperatures have averaged 1.5 Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) higher than the mid-19th century when the Industrial Revolution took off.

This summer in the Northern Hemisphere, temperatures have never been hotter. Is this because of a strong El Niño happening in the Pacific, or is this more evidence that we are losing the battle to mitigate global warming?

The warming isn’t just happening north of the equator. Scientists monitoring sea ice surrounding Antarctica indicated that the maximum reached as of September 13, 2023, was 1.75 million square kilometres (676,000 square miles) less in extent than the mean based on data collected between 1981 and 2010. Antarctica has seen rainy days over the past few years, a rare phenomenon for a continent encased in snow and ice. With less sea ice, the Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica is warming which accelerates the loss even more.

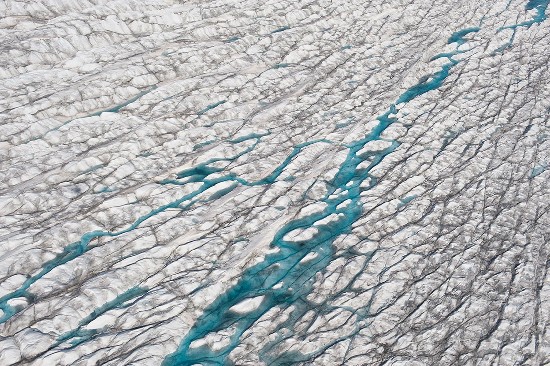

The Arctic Ocean, in recent years, has seen some of its lowest sea ice maximums but compared to the Antarctic appears more stable. Greenland, however, is exhibiting losses similar to those observed at the southern pole. Named Greenland by early Viking explorers who colonized areas along the coast during the Medieval Optimum, the island may soon begin to earn its green moniker again as it experiences accelerated meltdowns of the island-wide ice sheet. The question that climatologists are asking is can the Greenland ice loss be reversed even if mean global atmospheric temperatures rise beyond 1.5 Celsius?

The latest climate modelling points to abrupt and rapid acceleration should mean atmospheric temperatures rise 2.3 Celsius (4.1 Fahrenheit). Nils Bochow, a climate scientist from The Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø, who is the lead author of a study appearing in Nature doesn’t believe that we are beyond the ability to stabilize and reverse the island’s ice loss even if we surpass these temperature thresholds. He notes, however, that acting now to mitigate global warming will be a good “bet against time” because “it gets only harder the longer we wait.”

The biggest threat from Greenland’s accelerating ice melt is the impact it is having on sea level rise now and in the future. The island contains enough ice to raise ocean levels by 7 metres (almost 23 feet). The current annual ice loss of 270 billion tons is raising sea levels by 4 millimetres (0.157 inches) per year. If the anticipated acceleration from rising temperatures occurs (highly likely) climatologists do not believe the entire Greenland ice sheet will vanish. And if climate mitigating actions throughout the rest of the century were to occur, mean global temperature rise could reverse. But ocean level rise amounting to several metres will be with us for centuries if not millennia in the future.

The Antarctic picture has enormous implications for the fragile wildlife that depends on the preservation of the Southern Ocean sea ice and stable climate conditions. The latest victims of warming in Antarctica are Emperor Penguins who have seen significant losses in numbers with the threat of extinction. And seal populations dependent on sea ice as their habitat are also imperilled.

Vishnu Nandan and Robbie Mallett, from the Universities of Calgary and Manitoba respectively, have been in the Antarctic working with a British project called DEFIANT (Drivers and Effects of Fluctuations in sea Ice in the ANTarctic) with plans to deploy ground-based radar to track sea ice conditions. The data the two have been collecting shows that Antarctic sea ice is thinning. As it thins it loses its white colour, becoming opaque and eventually translucent. When white the ice reflects solar radiation. When opaque and translucent, it absorbs solar radiation converting it to heat. Polar oceans that warm are linked to climate disasters happening elsewhere on the planet.

All in all, the longer we wait to mitigate global warming, the more devastating the consequences. We can reverse temperature rise by eliminating the burning of fossil fuels. But the polar regions will have warmer oceans and changes to the life that has adapted and thrived there since the onset of the Ice Age some 2.58 million years ago.