February 18, 2017 – We think of the Neolithic or Agricultural Revolution as the defining beginnings of modern human civilization. With the rise of farming, humans moved from hunter-gatherers roaming over hundreds to thousands of square kilometers of territory to sedentary lifestyles, tending fields and livestock. In his book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Yuval Noah Harari describes the Agricultural Revolution as “history’s biggest fraud.”

What the Agricultural Revolution gave humanity was a larger volume of food but not a better diet states Harari. It created a population explosion but the life of farmers was considerably harder than that of ancestral hunter-foragers. When there was a dearth of food sources, hunter-gatherers could move on. That luxury of choice didn’t exist for farmers who were tied to their plots of land.

What moving from hunting to farming did do was hook humanity to annual staple crops like wheat, corn (maize), and rice. Domesticating wild versions of these plants meant more food could be harvested per square kilometer of land. And while we domesticated plants we also selected a number of animals that we could domesticate. Sheep, goats, cattle, horses, pigs, chickens and camels were incorporated into our Neolithic way of life.

The worst choice we made was becoming dependent on annuals. It meant a labour-intensive endless cycle of preparing ground, seeding, weeding, and harvesting. If there were drought or flood, an entire crop could be lost, leading to mass starvation. The only way to ensure a continuous supply of food was to over produce, creating surpluses to bank in case of disaster.

We could have picked better crops, ones that didn’t need such intensive care and maintenance. We could have picked perennials and not annuals. In Asia, where we took a native perennial plant, rice, and turned it into an annual, we gained in yields but intensified the labour needed to sustain the plants. And with wheat and corn, we picked plants that died every autumn, and that only reappeared if they reseeded themselves while in a wild state.

Modern agriculture is attempting to redress those initial errors of the Neolithic Revolution. Researchers have tried to develop perennial versions of the crops with which we, today, are so heavily dependent. The tools we used in the past, selective breeding and cross-breeding of varieties of wild and domesticated plants, have worked to some extent. But now that we have the means to analyze or alter the DNA of plants, we can examine the genetic makeup of new varieties which leads to better experimental results. This is helping to create the first of the staple crops we describe below.

One issue in developing perennial substitutes for annual crops, speed of maturation, remains unresolved. Perennials take longer to grow because they develop more extensive root systems. When we can speed this process up we will have the best of both worlds, staple crops that don’t need to be replanted and produce yield equivalencies in the same amount of time as the annual crops we grow today.

So where are we currently with perennial staples?

Perennial Wheat – Kernza, a perennial wheat developed by the Land Institute in Salina, Kansas, produces 20% more protein, more fiber, double the level of omega-3 fatty acids, five times the calcium and ten times the folate of traditional wheat crops. The challenges with Kernza, have been in size of yields and speed of maturation. Kernza grows more slowly and produces a smaller crop. The flour is considered excellent for biscuits, cookies, crackers and muffins, but not so much for bread.

Now joining Kernza is Salish Blue, the product of researchers at Washington State University who published their results recently. The formal Latin name for this new perennial wheat is Tritipyrum aaseae. Intense genomic analysis of the DNA combined with 20 years of breeding and cross breeding produced the Salish Blue, a stable perennial.

One of the most important benefits that will be derived from widespread planting of perennial wheat will be the impact on soils. On farms where extreme drought or rain can destroy fertility and viability of the soils, perennial grains will be much better at retaining moisture, organic matter and minerals, while at the same time, there will be less need for replanting, less plowing and less labour.

Salish Blue seeds have a blue tint. Normal annual wheat is either white or red. Salish Blue grows to 1.5 meters (about 5 feet) in height. That’s a half meter or more taller than annual wheat grown today which is called dwarf wheat. The tallness should help produce better moisture retention and soil protection.

Perennial Rice – In the last year China has begun field trials with a new variety of perennial rice. This is indeed an exercise in reversion. Almost ten millennia ago rice was a perennial grass that grew more than 4 meters in height on the edge of streams. It produced small red grains. Within a millennium that crop was genetically altered through selective breeding to become an annual that today provides the bulk of nourishment to half the planet.

But scientists in China have been observing how climate change is impacting growing areas from irrigated paddies in the lowlands to upland hillsides. Multiple plantings per year in conditions where precipitation has become less predictable is degrading soils and causing erosion. The search for a perennial rice would alleviate the planting cycles and hold soils in place.

The Academy of Agricultural Sciences completed a ten-year breeding program to create perennial rice varieties. One strain, for the last four years, has produced yields close to those obtained from conventional rice. It is called PR23. If the new field trials can match the success of controlled plantings then China intends to make it available to farmers within the next year.

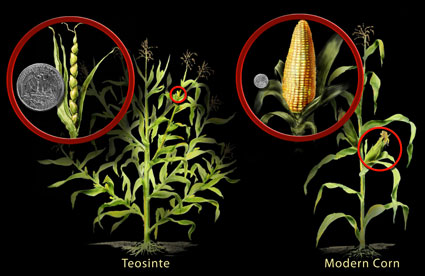

Perennial Corn – Corn is a staple found throughout the Americas, Europe, Asia and Africa. Corn, like rice, was probably derived originally from an ancestral perennial that resembles the plant’s wild relative, teosinte. Today, teosinte varieties are still found in Mexico and Central America where the plant was originally domesticated almost 9 millennia ago. One variety in particular, Zea mays, subspecies parviglumis, is believed to have spawned the modern corn plant. Zea mays is a perennial.

Back in the 1982, a collaboration between Argentina and the United States, reported in the New York Times, was said to have produced a perennial offspring from cross breeding Zea mays and modern corn. Harvard University, University of North Carolina, and University of Buenos Aires, partnered in the development of this new hybrid.

Since that study nothing else has appeared, which suggests that field trials didn’t produce desired results.

Perennial food security continues to be sought by agronomists. If successful, it could mean billions of dollars in industry savings. It certainly would be disruptive to the existing agro-chemical companies that count on annual seed sales plus the fertilizers, herbicides, and insecticides needed to produce quality yields. And it would finally correct the mistake our ancestors foisted upon us when they seemingly chose wrong at the beginning of the Neolithic Revolution.