April 25, 2014 – One of the ways we can capture CO2 and permanently store it underground involves binding it to an existing rock. In nature this has happened throughout Earth’s geologic history. The type of rock most suitable is basalt, formed from lava flows produced by volcanoes. Back in August of 2011 I published a posting in which I described CO2 capture technology involved with injecting the gas into rock formations to permanently bind it by altering the rock’s chemistry. A number of experiments have been conducted to-date.

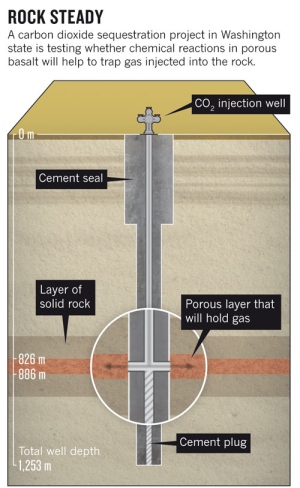

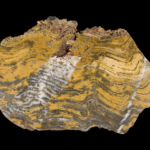

In 2013 American scientists pumped 1,000 tons of CO2 into porous basalt formations located in the State of Washington. The rock appeared to be an ideal medium for a pilot carbon sequestration project. It was laid down 16 million years ago and as it cooled formed basalt layered with holes. The CO2 was liquefied and pumped into the ground (see illustration below) where it began the process of binding with the chemicals within the basalt converting it to limestone. The mineralization process was expected to take up about 20% of the CO2 within 10 to 15 years.

But new pilot projects involving sequestering CO2 in basalt are showing much faster mineralization results. Researchers from University College London and University of Iceland at one of Iceland’s geothermal power plants (see photograph taken by Paul A. Souders/Corbis below) have been adding CO2 to water normally used in operations and pumping that water into basalt formations lying 400 to 700 meters (1,300 to 2,300 feet) underground . Within a year 80% of the CO2 has mineralized the basalt into limestone and other calciferous rocks. Such a quick conversion was totally unexpected.

The downside to the Iceland pilot project is the volume of water required for the chemical reaction to take effect. A volume of water 10 to 20 times the mass of the CO2 being captured and stored currently makes this technology economically untenable. But if the costs drop, this form of carbon sequestration is far safer than other technologies being deployed and tested for removing CO2 from the atmosphere.

Finding other basalt formations porous enough to take the volumes of water involved represents another challenge. Not all basalt rock is as porous as that used in the American experiment or the ongoing pilot in Iceland. Along the Ring of Fire geologists, however, should be able to identify similar basaltic formations that would be suitable sites for carbon capture mineralization projects.