In a recent study of the North Atlantic Ocean oceanographers took water samples to depths of 33 meters (+100 feet). The results surprised the scientists. Plastic garbage was evident not only in surface sampling but at all depths. We humans are creating an environmental nightmare in our oceans and need to address it now. There are 46,000 pieces of plastic per square kilometer in the world’s oceans today.

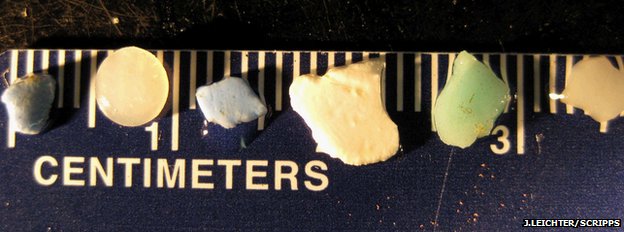

Less than 10% of the plastic we create gets recycled. So it is no surprise that plastic gets into our oceans and has become a major pollutant. Plastic pollution comes in all forms from microscopic fragments to large pieces.

What you see on the ocean surface today represents 1/17th of what is actually in the ocean. Small plastic particles are almost indistinguishable from zoo and phytoplankton. Marine animals from small fish to baleen whales ingest it. A recent Scripps Institute study reported that 9% of Pacific Ocean fish have plastic content in their stomachs. Plastic pollutants contribute to the death of hundreds of thousands of birds, fish, turtles and sea mammals annually. Small particles of plastic become breeding grounds for algae blooms and bacterial concentrations that contribute to ocean dead zones. Floating plastic combines with other debris to create mats that continue to grow in areas of the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

Plastic water bottles, bottle caps, plastic bags and cellophane wrap are floating platforms for barnacles and other sea life. A Scripps Institute of Oceanography 2012 report found an insect species flourishing in mid-ocean that more often finds its habitat along marine coastlines. That insect, the Pacific Pelagic Water Strider, is thriving in ever increasing numbers in mid-ocean because the garbage patches we have created offer it a stable floating platform for survival.

Plastic takes centuries to breakdown into chemical polymers. It does this when exposed to sunlight for a prolonged period, up to 500 years. So at best during our lifetime the plastic we throw away may break down in sunlight into small pieces. No creatures intentionally will eat plastic because it is indigestible. So over time in the ocean it just becomes a bunch of small fragments floating in a soup of debris.

Some would argue that the plastic serves the same purpose as floating rafts of seaweed. They point to natural occurring gyres such as in the North Atlantic where the Sargasso Sea features an accumulation of floating seaweed that is teaming with zoo-plankton, phytoplankton, crabs, crustaceans and fish. Because the North Pacific doesn’t have an equivalent to the Sargasso Sea, these same folks would argue that we, through our actions, have created an artificial equivalent in the North Pacific as well as the other zones in mid-ocean areas of the planet (see map below).

The argument of course is baseless. Yes lots of life finds its way to the floating plastic and debris in these gyres but so does death because plastic is a toxin in so many ways.

What Can We Do About It?

Humans have to act in two ways if we are to end the threat to our oceans from plastic and other floating debris. First we must reduce, reuse, recycle or repurpose all of the plastic we currently use in our modern world. Second, and much more challenging, we must develop technology capable of removing plastic and floating debris from the ocean.

Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, Repurpose

Humans respond better to carrots than sticks. If the phrase is unfamiliar to you then let me explain. When you want a mule to pull a cart you can offer him a carrot by waving it in front of his face so that he moves forward to grab and eat it. Or you can get behind the mule and whack it with a stick and accomplish the same result.

Recycling programs today are more sticks than carrots. Reducing plastic use is more a stick policy than a carrot. And because the political will to create carrot policies seems non-existent we end up with weak sticks and poor programs for tackling our plastic waste problem.

I’ll give you an example. In Toronto where I live we get charged a nickel (5 cents) for every plastic bag we request from a store for carrying the things we buy. Is this a sufficient deterrent to reduce the use of plastic? Initially there was a small drop in plastic bag volume. But the nickel charge has hardly made a dent. People pay the nickel and bring the bags home to use them in garbage receptacles. So the plastic ends up in landfill and dumps. And some of it ends up in our rivers and lakes and finds its way out to sea.

What would be a more effective policy? A bigger stick! This could be accomplished by charging much more than a nickel to discourage use of plastic bags. For those still inclined to purchase plastic bags a carrot would be assigning the money collected to environmental cleanup projects. But the best policy would be banning plastic bag usage entirely.

But plastic bags are just one of many plastic products that make their way into our recycling bins and garbage. In Toronto as in many North American cities homeowners are encouraged to recycle plastic as an environmental responsibility. The carrot here is the good feeling that comes from making a dent in what we end up throwing away. The city tries to make it easy by issuing a special rolling bin where we can dump all of the recyclable plastic, aluminum, metal cans, and paper that we would normally put in the trash. Our city picks up these items, sorts and sells them, a very big carrot. But much of what is recycled turns out to have no recyclable value and ends up in landfill. That’s because people recycle plastic that is not commercially reusable today or because the city collects so much that its ends up with a surplus and no current buyer or place to store the recyclables.

How can we repurpose the plastic we cannot recycle? Plastic is a polymer. It is an oil-based product. If we can reuse it by melting it to form new plastic items why can’t we use it by turning it into other products such as gasoline and diesel? Since it is oil-based why can’t we use non-recyclable plastic as a fuel for generating energy? The technology to do this exists today but there seems to be a lack of political will to do it, or the economics just don’t add up. This is where we need to apply both sticks and carrots.

We need to apply the stick to our governments. Governments that don’t advance the cause of environmental best practices should be voted out and replaced by those who have the political will to legislate. And we need our governments to create carrots that reward those who build innovative technologies to repurpose plastic.

Cleaning Up the Oceans of Plastic

Project Kaisei is a not-for-profit organization dedicated to cleaning up the North Pacific Gyre. Funded by other not-for-profits, private companies, associations, universities and charitable donations, the organization is developing and testing methods for marine debris retrieval with the goal of converting what is recovered into fuel or other plastic products.

The Clean Oceans Project is another not-for-profit focused on developing technologies to assess plastic debris concentrations and test technologies that can harvest the debris for plastic-to-fuel conversion.

But not-for-profit efforts won’t cut it in the long term. Governments have to get involved and provide sticks to plastic makers and carrots to innovators who develop technologies that recover the plastic debris and find a useful purpose for it.

Governments have to initiate carrot and stick policies that keep new plastic on land where it cannot get into the ocean. Government has to incent the plastics industry to find ways to make the plastic they produce rapidly biodegrade after usage.

The merchant fleets of the world, manufacturers and government need to stop the use of plastic pellets for filler in the packaging and shipping of goods. Called nurdles, billions of kilos are manufactured annually ending up in the growing mass of floating debris that characterizes our oceans today.

[…] can persist in the environment for decades and even centuries. In a 2012 posting, I reported that plastic was in evidence throughout the entire water column in ocean water samples […]