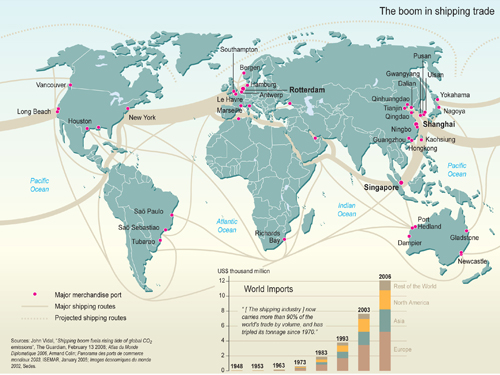

December 5, 2015 – The International Maritime Organization (IMO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations focused on shipping. Its mandate includes marine pollution, safety and security. With 90% of global trade carried by ships (see map below) the contribution that these vessels make to greenhouse gas emissions is an enormous issue for the planet today and going forward. Along with aviation the two transport modes will contribute up to 40% of global greenhouse gases by 2050 if emissions remain unregulated.

Most ships today run diesel engines using heavy bunker fuels. These are the dirtiest fossil fuel products other than coal. They produce high levels of particulate matter and greenhouse gases. The need to create a means to a low-carbon future for this industry is, therefore, critical. That’s why IMO is very much present at COP 21 climate conference in Paris.

Although originally established to focus on maritime safety, the environment has very much become a centerpiece of IMO’s mandate. This includes both ocean and atmosphere with an international antipollution convention first established back in 1973, focusing on the former, and with extensions in 1997 to include the latter.

As part of the draft text in the COP 21 agreement the following language appears:

“Parties shall pursue limitation or reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from international aviation and marine bunker fuels, working through the International Civil Aviation Organization and the International Maritime Organization, respectively, with a view to agreeing to concrete measures addressing these emissions, including developing procedures for incorporating emissions from international aviation and marine bunker fuels into low-emission development strategies.”

The language is vague. Originally the text had been removed from previous drafts only to be reinstated just before the opening of the conference. Described as one of “the elephants in the room” at COP 21, maritime shipping cannot be given a free pass as nations try to reduce carbon emissions. Without regulation of the world’s ships and their emissions it will be virtually impossible to achieve the stated 2 Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) degree warming limit that nations have signed on to.

The burning of bunker fuel today represents the most significant contribution to atmospheric carbon emissions by the industry. In 2007 it amounted to 2.7% of global emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2). But CO2 is not the only greenhouse gas produced in burning bunker fuels. Other pollutants include sulphur oxides, nitrogen oxides, ozone depleting gases, volatile organic compounds and particulate matter.

A study commissioned by the European Union considered a 20% CO2 emission reduction target below 2005 levels by 2020 for marine shipping. The target was proposed so that shipping would be treated in the same way as other industry sector targets in achieving Europe’s overall reduction commitment. Added to this were two additional recommendations: one for new ships built after 2013 to adopt mandatory emission reduction technologies, and the second, for the implementation of an energy efficiency management plan to govern shipping. Under the second recommendation monitoring would include CO2 and other pollutants at all European Union ports of entry beginning in 2018. Could what Europe has proposed become the global standard?

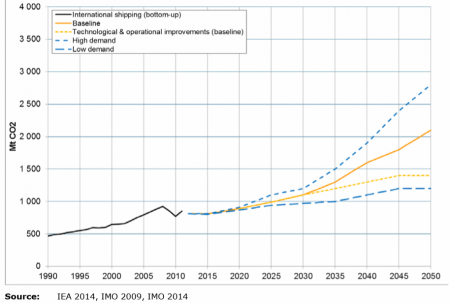

Currently IMO projections show maritime traffic CO2 emissions growing projected to 2050. The graph below, with its solid yellow centre line, represents total base projections with more than doubling of current emissions by mid-century. Why? Because shipping volume is expected to more than double over that projected period. So even if pollution abatement controls were put in place total emissions would continue to rise.

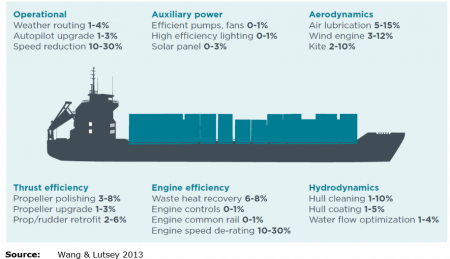

A move away from the use of bunker fuels would very much help mitigate the rise in emissions. Projects like the Ecoship, described in a previous posting (an being unveiled at COP 21 today) is just one example of radical new approaches to marine locomotion technology. Other options include using hydrogen fuel cells, biofuels, synthetic kerosene, liquid hydrogen, liquid natural gas, super capacitors and hybrid technologies. In past postings I have described some of these. The illustration below summarizes some of these innovations.

Industry optimists believe it is possible to reduce CO2 emissions per ton-mile by 50% in 2050. But the only way this intensification target will be achieved is through a carbon levy, a tax on emitters.

In a table appearing in that same European Union report CO2 emission reduction projections needed to keep temperatures from rising more than 2 Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) are suggested. These include:

- a 12% reduction by 2020

- 25% by 2030

- 61% by 2040

- and 98% by 2050.

Current forecasts, however, paint a much more dire picture with projections showing maritime shipping contributing a tripling of emissions between now and 2050. So let’s hope that the nations of the world and IMO begin to set some hard targets for the industry.

A hopeful note.

A Hong Kong based company has collaborated with the University of Southern California to develop nano-pulse technology that improves fuel efficiency and reduces nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions at the exhaust point in ships. A recent series of sea trials demonstrated 90% NOx emission reductions and 75% reduced particulate matter. The technology can replace post-combustion scrubbers which in older ships are prohibitively expensive add-ons.

States Kenneth Koo, the CEO of the Hong Kong company, “The maritime industry has been slow in identifying emissions caps since the Copenhagen Summit six years ago. Marine diesel engine combustion efficiency must become the focal point because present designed combustion efficiency peaks at 50 percent, meaning that half of the heavy fuel oil (bunker fuel) ends up as unburnt hydrocarbons, which are then emitted in the form of harmful CO2, NOx and other particulate matter.”

That’s the problem well articulated by an industry member. It seems technological solutions can be found.