April 11, 2016 – Canada is a member of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) which creates a common market for the continent. In fact the country has 12 existing free trade agreements (FTA) in place and one, the Trans Pacific Partnership, signed but under scrutiny by the new federal government. In addition the country is in ongoing negotiations for twelve more FTAs.

Why?

Because for Canada, a vast country in physical size with a population of under 36 million, international trade is a necessity for its business community. The domestic market remains small while the resource capacity exceeds consumer demand making trade imperative. With no built-in consumer market like that in the United States, 10 times larger in population, or China, almost 40 times larger, exports are critical for economic sustainability.

Trade activities, however, have consequences. One is they contribute to climate change. So how does signing another FTA help Canada meet greenhouse gas reduction targets under the COP21 Agreement signed in Paris?

The truth is “unknown.”

Are FTAs potentially incompatible with fighting climate change? Some say yes because trade requires transportation, and it is responsible for 26% of total greenhouse gas emissions in the country today. Compare that to global statistics where it is 30% in Developed Nations and 23% in the Developing World. That’s a lot of greenhouse gases in a national budget and suggests that FTAs are indeed a threat to establishing a low carbon economy.

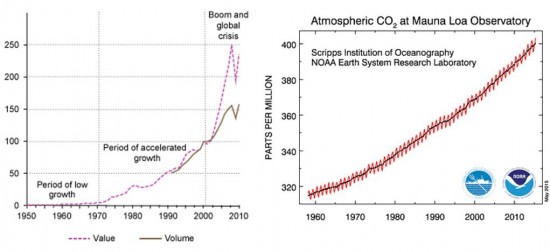

Whether by ship, airplane, train or truck, the energy that transportation uses to drive trade relies on fossil fuels. And where you burn fossil fuels you get carbon emissions. The two graphs below, the one on the left plotting global trade growth, and the one to the right, increasing CO2 emission levels, have remarkable similarities.

Since 1950 world trade has expanded by 2700% while CO2 levels have risen by more than 40%. This rapid trade expansion has been noted by those studying climate. Lowered trade barriers and the rapid expansion of trade correlates to CO2 emission level rises.

Economists point out that FTAs change the economic activity of countries. They cite three independent effects:

- Scale – freer trade increases economic activity which means more energy is used and more greenhouse gases get created.

- Composition – as countries trade the economic activities within them change. Resources are reallocated to create efficiency and comparative advantage. That means in some cases local manufacturing dies and is replaced by imports. The balancing act between the lowering of local greenhouse gas emissions from declining manufacturing may be more than offset by the global warming contributions made by the exporting country and transportation needs.

- Technique – trade can produce efficiency so that production of goods and services become less energy intensive. Through emission intensity improvements increased trade volumes can mitigate carbon emissions.

These three can work at cross purposes and based on the magnitude of each may lead to a net increase in carbon emissions. This presents a real challenge to economies trying to address growth and climate change at the same time.

In “scale” we deal with the direct impact of increased transportation and its global warming contribution. Today 95% of the energy used in world trade is petroleum-based. Almost 75% of trade CO2 emissions come from road transport. The remainder is almost evenly divided between air and marine sources.

For maritime shipping representing 90% of global merchandise by volume it would seem the contribution to global warming is minimal even at slightly under 10%. But 10% of emissions is still a significant number. That’s why MARPOL, the organization responsible for maritime shipping, has taken initiatives to research new technologies and made an attempt to voluntarily manage emissions by changing the types of fossil fuels used.

In the North American free trade zone trucks are the predominant conveyors of goods and “food miles,” the transportation of food over long distances from growers to consumers, represent a significant amount of that volume. A trip to the Detroit-Windsor Ambassador Bridge, joining Canada and the United States (see image below), gives you a feel for just how massive these transportation volumes are in North America. This site is the busiest international border crossing on the planet. Hundreds of billions of dollars flow across the border each day.

What’s the alternative to all this movement of goods?

Advocates of “local grow” argue that one way to lower our collective carbon footprint is to stop buying blueberries that get trucked in from Florida, or flown in from Argentina, or peppers and melons that come by truck from Mexico. “Local grow” advocates argue we should be building greenhouses and growing food items in our own backyards. But the greenhouse gas impact of “local grow” production when compared to the “carbon mileage” of imported foods produces some interesting statistics.

A number of studies have shown that “carbon mileage,” that is the CO2 emissions produced in getting goods from point of origin to consumers, can be less impactful on the environment than goods produced locally. Here are some examples. The carbon footprint of flowers grown in Kenya and air-freighted to Europe is less than growing the flowers in Europe. Similarly, the carbon footprint from roses grown in Ecuador and sold in Canada is smaller than locally grown and harvested roses. Lamb produced in New Zealand and imported to Canada has a smaller carbon footprint.

So as Canada reviews the Trans Pacific Partnership Agreement and any others that it chooses to enter into or revise the country faces the dilemma of reconciling its climate change targets with trade ambitions.

These agreements need to have regulatory measures in place that on a national and regional level measure carbon impact. And when measuring impact they need to put a price carbon in the form of a tax per ton or through market-based mechanisms such as cap-and-trade. The just signed Trans Pacific Partnership needs to be scrutinized under this lens. And so should all future FTAs the country negotiates. Any agreement must help meet Canada’s carbon emission reduction targets. Unit “emission intensity” must be a measure in the mix of trade goods and services. “Food miles” and “carbon mileage” should be a measure of trade goods and services. This is no longer just about lower tariffs and industry exemptions. A sustainable economic future where trade plays a part has to deal with carbon.