October 20, 2018 – I have waited more than one week to assess the meaning of the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change special report summarizing the present state of our collective efforts to slow down greenhouse gas emissions and rising mean atmospheric temperatures. Why a special report? Because the IPCC agreed to share publicly periodic progress by the nations of the world who were signatories to the Paris Climate Agreement signed at the COP21 meeting. At the time almost every country on the planet signed on to voluntarily create policy to help keep atmospheric temperatures from rising above 2.0 Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit), and to try for a lower threshold of 1.5 Celsius (2.4 Fahrenheit) because of what the half-degree difference would mean in terms of mitigation and adaptation requirements. At the time of COP21 human activity was seen to be the cause of a mean temperature rise approximating 0.87 Celsius over the average global temperature between 1850 and 1900. That meant in 2015 we were already past halfway in seeing mean atmospheric temperatures rise to 1.5 Celsius. So significant action was deemed to be required if we were to hold the threshold to the lower target number.

The special report measures just how ineffective governments have been. The condemning evidence is undeniable:

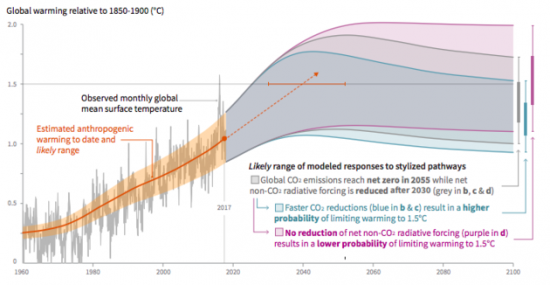

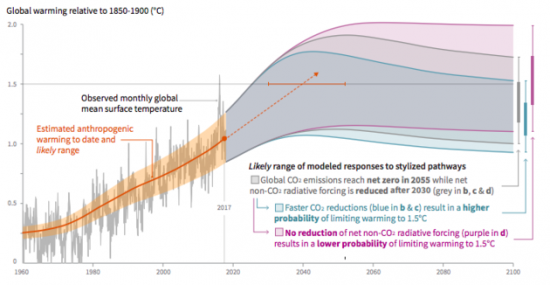

- Anthropogenic warming of the atmosphere is already 1.0 Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

- At the current rate of warming, (about 0.2 Celsius per decade) we will reach 1.5 Celsius between 2030 and 2052.

- Atmospheric warming is uneven across the planet with some regions (particularly the Arctic) experiencing increases two to three times the mean.

- Warming over land is happening faster than over water so the average increase does not reflect how much continental temperatures are exceeding the mean rise.

- The anthropogenic climate change being seen globally in temperature rise is leading to increased extreme weather and is no longer seen as coincidental.

The report also states that regardless of what actions we take starting today, what we have presently put into the atmosphere to increase mean global temperatures will continue to persist for centuries and millennia.

The difference between 1.5 and 2.0 Celsius is seen as significant in terms of the level of mitigation and adaptation that will need to occur for a significant portion of the planet.

As for warming over continental land masses, the difference between a 1.5 and 2.0 Celsius rise translates to temperatures much higher than these two means. Extreme hot days in mid-latitude locales at 1.5 Celsius as the global mean translates to 3.0 Celsius. And at 2.0 Celsius as the global mean, to 4.0 Celsius. Meanwhile, in polar locales, nighttime low temperatures could increase by 4.5 Celsius in the 1.5 scenario, and 6.0 Celsius at 2.0. In tropical zones the number of extreme hot days will grow regardless of the rise in the global mean temperature.

Drought risk and precipitation deficits will be worse at 2.0 Celsius compared to 1.5. And so will extreme precipitation events including tropical storms like hurricanes and typhoons. Higher incidents of flooding will occur at 2.0 Celsius compared to 1.5.

Sea level rise will also vary based on the mean temperature rise. Total average rise by 2100 will be 0.1 meters lower if the mean temperature can be contained to 1.5 Celsius as opposed to 2.0. The slower rate of sea level rise will give coastal populations and low lying islands greater opportunity to adapt. The 0.1 meters less of sea level rise will spare at least 10 million of us around the world from seeing our homes vanish under water.

Even if we cap the temperature rise at 1.5 Celsius, sea level rise will not abate. The report states the instability already evident in Greenland’s ice sheets, and the Antarctic Peninsula, as well as changes to sea ice will have long-term implications leading to sea level rises in the multi-meter category.

The impact on biodiversity and ecosystems on land will be less at 1.5 Celsius than at 2.0. Nonetheless, the 1.5 Celsius rise will impact 105,000 species including 6% of insects, 8% of plants, and 4% of vertebrates who will see their natural habitats shrink by half. But at 2.0 Celsius the impacts on that same number of species will rise to 18% for insects, 16% for plants, and 8% of vertebrates. Polar tundra and boreal forest habitats will be most at risk.

Keeping the difference to 1.5 versus 2.0 Celsius will mean a reduction in the threat to permafrost areas affecting between 1.5 and 2.5 million square kilometers.

As for the oceans which will be impacted not only by temperature rise but also by increased acidity, the delta between 1.5 Celsius and 2.0 is significant with the lower mean rise reducing the risk to marine biodiversity, fisheries, coral reef ecosystems, and Arctic sea ice. As for the latter if the temperature can be held to a mean rise of 1.5 Celsius it is unlikely that the Arctic Ocean will see one sea-ice free summer within this century. But at 2.0 rise the one sea-ice free summer will happen once a decade.

The global fishery will see declines in annual catch of 1.5 million tons at 1.5 Celsius, and 3 million tons at 2.0. Acidification will be bad regardless of whether the rise is 1.5 or 2, but the problem will be amplified more with the latter rather than the former. For marine life requiring calcification for survival, global warming will have adverse to catastrophic effects.

And then there is human health. Food security, freshwater, work, and economic opportunity will be affected regardless of the rise being 1.5 or 2.0 Celsius. But the higher temperature will have greater negative consequences. Heat-related morbidity and mortality will rise. Urban heat islands will further amplify the average rise over land. Diseases such as malaria and dengue fever will see geographic shifts in range. And limiting warming to 1.5 Celsius versus 2.0 will mean smaller net reductions in cereal crops particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America where human population growth has been highest in the last half-century and where food security today is at greatest risk.

The report sets the target to limit global warming to 1.5 Celsius. It involves staying within the CO2 emissions cap by reducing our current contributions by 2,200 Gigatons or 42 Gigatons per year. Greenhouse gas reductions of 35% from 2010 levels to 2050 for methane (CH4) and black carbon aerosols will also be needed. Similar targeted reductions are necessary for nitrous oxide (NO2) and CH4 from agricultural and waste sources. Further adjustments to these reductions will be needed to offset increases in atmospheric CH4 from permafrost melt and wetland releases.

Probably the most troubling issue of this 2018 report is the willingness to embrace geoengineering solutions to remove CO2 as well as consideration for solar radiation management to offset the effects of greenhouse gases rather than remove them. Geoengineering involves applying laboratory experiments on a planetary scale. To describe it as the Hail Mary option for dealing with climate change seems appropriate. For those of you unfamiliar with the term, Hail Mary, it is associated with the game of North American football, where, in the dying seconds, a quarterback throws the ball 50 plus yards down the field in desperation hoping that one of his receivers will catch it in the opposing team’s endzone to grab victory from the jaws of defeat. On rare occasion, the Hail Mary strategy succeeds. But most of the time the outcomes from the effort don’t end well.

Solar radiation modification would be a Hail Mary. By putting aerosols into the stratosphere we would reduce the energy from the sun reaching the troposphere (where we live and breathe) to create cooling. We would have to do this continuously without knowing if there would be unintended consequences such as shifting precipitation patterns, or changes in extreme weather frequency. The risk of termination shock should we suddenly stop doing this form of geoengineering could be more significant with global temperatures rebounding dramatically over a short period of time.

On the other hand, removing CO2, a practice already being done at various locations around the planet, would be a form of geoengineering with fewer risks. CO2 can be captured at emission sources which is currently being done at a few sites today. CO2 can be directly captured from ambient air. There are a few projects like this on the go today. And CO2 can be captured through natural processes such as changing agricultural practices to sequester it in soils, or afforestation.

Capturing and sequestering CO2 on an industrial scale has yet to be fully implemented. But if it were, the planet might be able to keep mean temperatures from rising beyond 1.5 Celsius. At the same time, we could achieve a negative emissions turning point and begin rolling back the levels of greenhouse gases our industrial society puts into the atmosphere watching the parts per million of CO2 and other global warming instigators decline. Maybe that can keep anthropogenic climate change to no more than a millennia.

If this report doesn’t alarm you then you are in denial about climate change and will face the consequences with the rest of us who recognize the crisis at hand. The human ability to deal with challenges is one of our great strengths as a species. And because we know the cause of the warming, carbon emissions, we should be able to come up with solutions in terms of government policies, personal lifestyle and behavioural changes, and in technology fixes that can help us make the best of a bad situation. One certainty arises out of the 2018 IPCC report. We must act now. To not do it would be anti-planet, anti-human, and criminal.

In a video statement made after the release of the IPCC Report, Catherine McKenna, Canada’s Federal Environment Minister stated, “We are the first generation to feel the impacts of climate change and we are the last generation [who can] do anything about it.” She’s right but increasingly, the message she is relating is falling on deaf ears.