July 19, 2017 – I asked myself the above question when the first images came in showing that the final piece of ice holding the Delaware-sized iceberg cracked open in the last month. After all, it is winter in the Southern Hemisphere and the Larsen ice shelf is in almost perpetual darkness.

So how did we know the event took place?

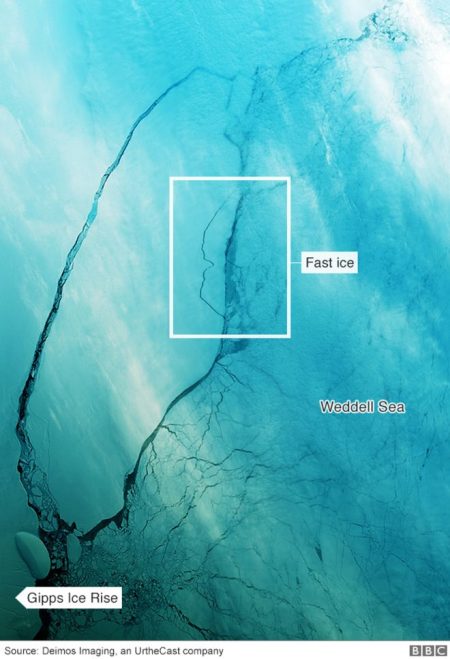

The technology that spied the final breaking off from Larsen C came from satellites using radar and infrared thermal imaging, not the traditional photographic pictures. NASA’s Aqua satellite captured thermal images of the ice revealing the warm water break between the berg and the ice shelf. And now almost a month into winter with enough light returned the first photographic images are available, taken by the Deimos-1 satellite.

In the above image, you can see, in the highlighted area, a new development. Sections of what is called “fast ice,” that is the thinner edge of the shelf that abuts the Weddell Sea is breaking away from the larger berg. The section seen here will remain in close proximity to the main berg itself until summer returns to the Weddell Sea and the sea ice begins to break up.

The berg has been given the name A-68. Who names them?

The U.S. National Ice Center (NIC), which tracks and analyzes icebergs, is the organization responsible for naming.

What qualifies it as an iceberg?

There is a classification scheme. An iceberg must float 4.87 meters (16 feet) above sea level. It must be between 30 and 50 meters (98 and 164 feet) thick. And it must cover an area 500 square meters (5,382 square feet). Icebergs are also classified as tabular or non-tabular. The Antarctic ice shelves produce tabular bergs, that is pieces of ice that are steep-sided and flat-topped. The glaciers of Greenland and the Canadian archipelago, the ones that drift by Newfoundland and Labrador providing incredible sights for tourists, are non-tabular.

A-68 certainly qualifies. It is almost 6,000 square kilometers (some 2,317 square miles) and more than 200 meters thick (656 feet).

Where is it headed?

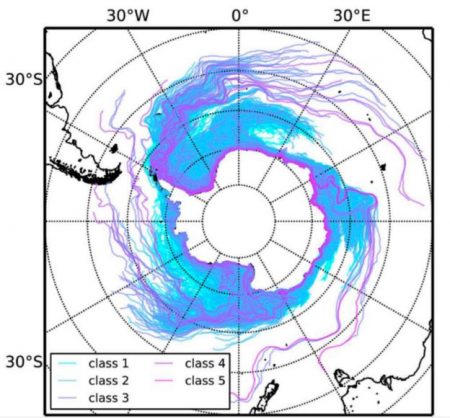

The future path remains unknown. Researchers have tried to model the drift looking at the changing conditions of the Weddell Sea and the South Atlantic Ocean. Most conclude it will head for South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. But there is no certainty here. Take a look at the map below which shows simulated tracings for major icebergs when calved off various ice shelves of Antarctica. The northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, seen on the left, is the starting point for A-68. Tracings from that location are too numerous to predict with any certainty where the berg will go.

What makes its path difficult to predict?

Scientists point out that the berg itself will change shape as sections of ice break off just like the “fast ice” section seen in the Deimos-1 satellite image. With each crack and calving, the berg will shift.

The removal of the berg from the ice shelf is expected to reveal a previously unseen ocean floor which will be an exciting location for scientists to search for yet undiscovered life.

In addition, with the berg separating from the Larsen C, scientists will closely observe the remainder of the shelf. In the past calving of large bergs in Larsen A and B, two sister ice shelves led to their disintegration within a few years.