In the IPCC’s 6th Climate Assessment Summary for Policymakers, the report provides a range of future climate scenarios described previously on this blog site, with suggested policies for adaptation and mitigation to address and reverse projected outcomes.

In advising policymakers, the report notes that every region of the planet will experience climatic impact drivers whether atmospheric mean temperatures rise 1.5 Celsius, 2.0, or higher. The higher the temperature, the more extreme the impacts will be on ecosystems, agriculture, and health.

If we can keep warming to 1.5 Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) then predictions rated as highly likely for the continents of Africa and Asia, which include extremes in precipitation and flooding, and in other areas, declines in precipitation with prolonged droughts can be mitigated. The current data indicates that the 1.5 Celsius ceiling will lead to lesser impacts in Europe and North America.

But if the atmospheric temperature rises by 2.0 Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit), then a magnitude of change in extreme weather conditions is expected across most of the globe including impacts to the Pacific islands, North America, Europe, Australasia, Central and South America, Africa and Asia. The latter two will see even more extreme climate events than what was described in the 1.5 Celsius scenario described in the previous paragraph.

Above 2.0 Celsius, tropical cyclones and extratropical storms will become more intense and frequent. Fire-weather seasons, such as we are seeing occur annually today across the Mediterranean Basin, North America, and Central Siberia, will lengthen.

Extreme sea-level events that occurred once a decade to once a century in the past, will become an annual thing leading to repeated coastal flooding in low-lying areas and erosion. With so many of Earth’s cities located at or near the coast, flooding of these communities from the combination of sea-level rise and storm surges from increasingly more frequent and intense tropical and extratropical storms will escalate.

Lower likelihood outcomes that are talked about in today’s newspapers on a semi-regular basis, such as the collapse of Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets, or abrupt changes to ocean circulation such as the shutting down of AMOC, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (expected to weaken but not stop in the 21st century) responsible for the Gulf Stream are less likely. Although the report states they “cannot be ruled out.” And neither can “abrupt responses and tipping points” including mountain glacier retreats, drying up of the rivers they feed and significant forest dieback.

Should the AMOC abruptly collapse before 2100, deemed a low risk at present, the changes to weather patterns and precipitation will be notable. Climatologists predict a southward shift in the tropical rain belt, a weakening of the African-Asian monsoons, a drying out of Europe, and increasing Southern Hemisphere monsoonal activity will ensue.

So what can policymakers do?

We already know the answer to the above question. The report states:

“From a physical science perspective, limiting human-induced global warming to a specific level requires limiting cumulative CO2 emissions, reaching at least net-zero CO2 emissions, along with strong reductions in other greenhouse gas emissions. Strong, rapid and sustained reductions in CH4 emissions would also limit the warming effect resulting from declining aerosol pollution and would improve air quality.”

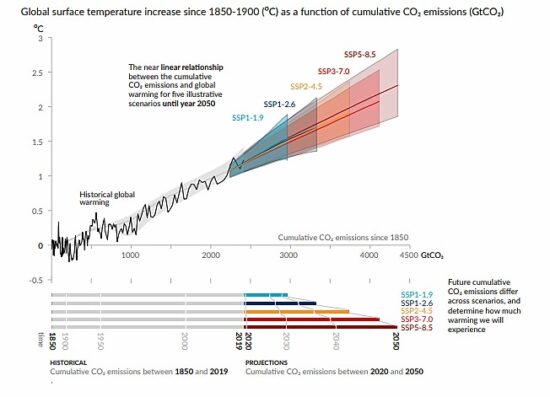

The linear relationship between atmospheric carbon emissions and the changes happening to the world’s climate requires us to act with one specific purpose: zero-out carbon emissions in the world economy using natural and technologically created sinks that will limit atmospheric temperature rise to 1.5 Celsius (2.4 Fahrenheit), the goal originally aspired to at the Paris Climate Agreement six years ago. That means all the nations of the world have to adopt a carbon budget in parallel with normal fiscal budgets. And that also means that these carbon budgets take precedent over all fiscal and economic decisions going forward.

If you are not familiar with the term carbon budget, it refers to the maximum amount of cumulative net global anthropogenic CO2 that the atmosphere can handle to keep global warming from topping the targeted mean temperature rise of 1.5 Celsius. The figure seen below which comes from the IPCC report illustrates the linear relationship between CO2 emissions and the warming atmosphere. The grey areas surrounding the central line show the corresponding estimate of historical human-caused atmospheric warming. The areas in colour show the likely range of global atmospheric temperature projections with the thick coloured central lines indicating the median estimate of cumulative CO2 emissions from now until the year 2050.

The challenge of sticking to a carbon budget when doing fiscal planning for an entire national economy, let alone a global one, is that much of the budget has already been spent. All we have left to work with is an increasingly shrinking remainder. That’s why what was thought of as unnecessary a few decades ago, such as mass-scale carbon capture and sequestration, has been adopted by the IPCC as important for national governments to implement. This is in addition to removing CO2 by natural means such as afforestation and reforestation, wetland preservation, and expanding natural grasslands and ocean kelp growth.

Policymakers need to understand that whatever we put in place today will only begin to have a net negative impact well into the future. That’s because we have already built into our planet’s atmosphere through our carbon expenditures, climate changes that will continue in the present direction for “decades to millennia.” As one example, the reversing of sea-level rise through the implementation of negative carbon emission policies will not alter the current trend of accelerating rise for several centuries to millennia. The damage is done.

And as for dealing with shorter-term emissions such as CH4, N2O and other aerosol and ozone precursors from the air pollution our modern industrial society produces, we will continue to observe net global atmospheric warming spikes until we remove the industrial sources of these emissions. Fortunately, these contributors to atmospheric warming and climate change can be addressed in the short term with notable impacts on health, and extreme heat and precipitation events.

Policymakers need to note that the work has to begin immediately in every country on Earth. Why? Because as we lower emissions we will begin to discern improvements to the global climate with the emergence of more of what we have known as natural variability as early as 20 years from now and throughout the remaining 21st century and beyond.

Beyond 2040, if we can rapidly approach net-zero emissions, we may be able to limit some of the more extreme changes we have described here, including diminishing the rate of coastal flooding, reductions in heavy precipitation and flooding events, and lessening the number of dangerous heat thresholds we surpass, the latter particularly in areas of our planet that within 30 years could become uninhabitable if we continue along our present course.