June 1, 2020 – The latest studies on COVID-19 show that this virus is a disease of the endothelium. In my personal journey with it, there is no doubt in my mind that this describes the experience I have undergone with a great deal of precision.

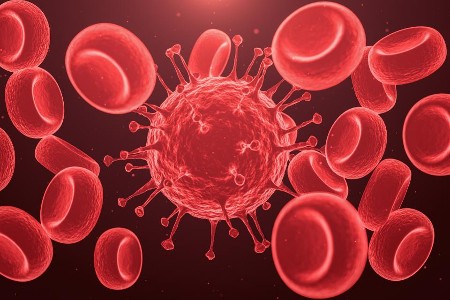

What is the endothelium? It is the layer of cells that line almost every part of our bodies, from our skin to the blood vessels and major organs. COVID-19 is proving to attack almost every area of our body where there are endothelial cells. It doesn’t do this to everybody. But it does it to enough people and in pervasive ways that make it far more dangerous than the influenza virus, or even its coronavirus cousins, SARS and MERS.

In my case it’s not just the fact that the virus attacked the lining of my heart, it affected my skin as well. In fact, I now believe that the earliest symptom of the infection wasn’t the hoarse throat that I developed or the coughing that followed. It was a roughening of the skin on my forehead that became itchy and scaly. This condition has lingered since its first appearance more than a month ago. Joining it has been a second skin eruption affecting my neck and wrists with blisters and a rash. It’s a contact dermatitis that reacts to any metal on my skin. So I can’t wear a necklace or a watch. Since removing them the skin has started to return to normal but has left me with scabs and reddening in a number of places.

The hoarseness in my throat which has been ascribed to the inflammation of the upper left chamber in my heart pressing on the laryngeal nerve has lessened considerably in the past week. Occasionally I experience coughing jags persisting for several hours and then vanishing for days.

The investigation of my heart condition included a series of tests and examinations done at the end of last week. I’ve been wearing a Holter monitor for the past 72 hours and just took it off 30 minutes ago. I should know the results when I reconnect with my cardiologist who I have yet to meet and have only talked to over the telephone.

When I was first diagnosed with a heart problem after being tested for COVID-19 I didn’t equate the two together. I don’t think my family doctor did either. But it turns out that injury to the heart muscle is a more common outcome for COVID-19 patients. In one Wuhan hospital in China, 12% of patients showed signs of cardiovascular damage after contracting the virus. Abnormalities were occurring to people with pre-existing heart conditions, undiagnosed cardiovascular problems, and those whose hearts prior to the virus were deemed healthy. Paul Ridker, a professor of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, in an article in The Harvard Gazette has described COVID-19 as “one big stress test for the heart.”

The condition it causes is referred to as myocarditis. This can be bacterial or viral in origin. Viral myocarditis isn’t exclusive to COVID-19. Many other viruses attack the heart including influenza. But COVID-19 seems to affect the heart muscle after the initial onset of the infection during a period when the viral load is no longer detectable. This is a post-viral inflammatory reaction that leads to heart rhythm disturbances.

In my case, the virus has caused atrial fibrillation and I have been put on a beta-blocker and a blood thinner. The latter appears to becoming a standard of care in COVID-19 treatment because increasing evidence suggests it targets our vascular system including the blood vessels in our lungs. This explains the pneumonia-like symptoms and shortness of breath that is often the primary symptom. It also explains why COVID-19 is associated with blood clots, strokes, and heart inflammation.

The Lancet has recently published research that links the virus to changes in endothelial cells lining the blood vessels causing inflammation. And The New England Medical Journal has described why respirators often don’t help because of endothelial cell damage to the lungs that makes the blood-oxygen exchange break down. So in effect, all the respirator ends up doing is trying to pump air into lungs incapable of receiving the needed oxygen.

A virus attacking endothelial cells is not unusual. Influenza viruses do this as did SARS, the original coronavirus. Ebola and Dengue both damage endothelial cells. But the difference between COVID-19 and SARS is that the latter largely confined its attacks to the endothelium in the lungs and not the entire body’s vascular network.

That may explain why COVID-19 causes such diverse and odd symptoms such as some of the ones that have happened to me as I have described above. I consider myself relatively lucky though, even with the impact on my heart. My wife, who also was infected at about the same time as me, and experienced coughing and chills initially, has a post-COVID series of symptoms that cause joint and muscle pain occurring periodically with no apparent cause. It is as if she had a bad case of fibromyalgia which she doesn’t.

Doctors describe COVID-19’s impact on the walls of the body’s vascular systems as being the most destructive aspect of the infection. The endothelial cells rupture and die, cause clots, and infect other organs other than just the lungs. States Vincent Li, one of the authors of the article that appeared in The New England Medical Journal, “Endothelial cells connect the entire circulation [system], 60,000 miles worth of blood vessels throughout our body. Is this one way that Covid-19 can impact the brain, the heart, the COVID toe?”

That latter condition along with other dermatologic symptoms is increasingly being described as part of the COVID-19 panoply of crazy-odd indicators. In COVID toe they discolour, develop lesions, and rashes. Other skin indications include bumps, burning, and itching. My toes never exhibited the COVID response, but my forehead sure has and my skin continues to tell me that I am having a post-COVID response likely caused by my immune system’s reaction to the infection.