Elon Musk is in a hurry to get humans to Mars by the end of this decade. NASA wants to put astronaut explorers on its surface sometime in the 2030s. The latest rover, Perseverance, is collecting samples that will be returned to Earth for study in the 2030s. Those samples may show us that Mars has life, or had life in the past. If the former, then I ask this question, “Why are we sending human expeditions to Mars before we know if life exists there presently?” Is our respect for alien life trumped by our need to get to that planet and disrupt its tenuous ecosystems?

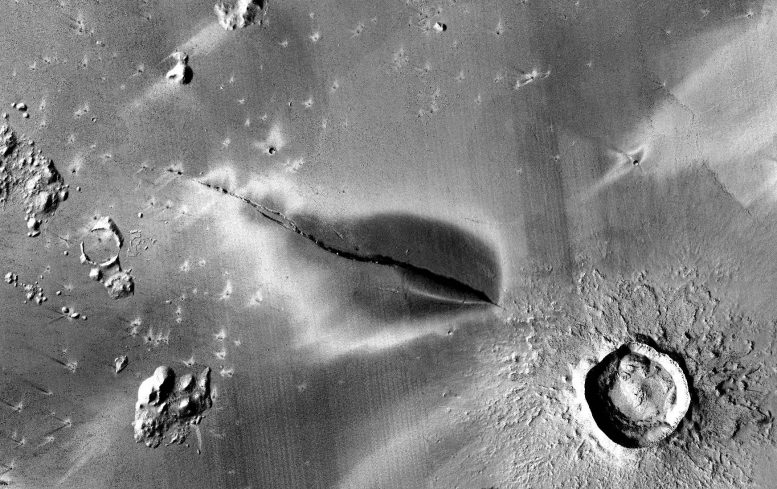

In some of the latest NASA MAVEN orbiter images, we now know that Mars has experienced recent active vulcanism. That was not thought possible by scientists who in the past have described the planet as largely geologically dead. But the evidence in the planet’s Elysium Planitia region clearly shows a recent pyroclastic eruption with ash deposits (the lighter materials seen surrounding the vent seen in the image below) raining down from the fissure after it cracked open the surface.

This volcanic eruption lies 1,600 kilometres (1,000 miles) from the site of the Mars Insight Lander which has been using its seismograph to record Marsquakes for the last three years. Many of those quakes originate from the area where the above image was taken.

So what does this have to do with present life on Mars? Plenty. That’s because beneath the red dusty surface of Mars are vast deposits of glacial ice. The interaction of hot magma rising through the ice presents conditions that could favour microbial life. In other words, at this site on Mars, not only is the planet not dead geologically, but it also may not be dead biologically.

How can we conclude this from looking at an open fissure on the Martian surface?

Using the example of the only planet we know of that currently supports life, our Earth, here beneath the surface where groundwater has been isolated for hundreds of millions to billions of years, we have discovered evidence of microbial life. It is non-photosynthetic. In other words, it exists and thrives without sunlight. Instead the life found here finds the energy it needs from the chemistry of the surrounding rocks. Natural radioactivity within subsurface rocks here on Earth serves to break down water into its molecular components, hydrogen and oxygen, creating suitable materials for supporting habitability.

Present-day Mars is similar enough in its subsurface composition to Earth. How do we know this? We know it from the composition of Martian meteorites dislodged from that planet that have, from time to time, arrived here on Earth and be identified and analyzed.

All of the above brings me to the question I first posed at the beginning of this article.

When I read about NASA’s goals in the Mars Exploration Program the first one is to determine if life existed on Mars in the past. Note that’s not if life exists today.

Goals that follow include studying the planet’s climate, and geology.

Then there is the fourth goal, the one I am questioning. It concerns preparation for the human exploration of the planet. NASA makes astronaut safety in the harsh environment of the Martian surface a major priority. It says nothing about making the preservation of Martian life a priority.

A visit to Mars by humans will introduce a vast biome of exotic life including the microflora and fauna that populate our external and internal bodies. How will we protect Martian life from being overrun by Earth microbiology? What precautions will Elon Musk or NASA take to keep what we bring to Mars from infecting the life presently on there?

If our future endeavours here on Earth in dealing with climate change are to do no harm, how can we not carry that principle to Mars?

I leave you with a cautionary tale that is unfortunately not fiction but very real. The European discovery of the Americas was an unprecedented event in human history. Before 1492, the Western Hemisphere consisted of a healthy, thriving community of humans, animals, and plants in reasonable balance. Within a century, however, more than 90% of native Americans had been wiped out by the microbiology introduced to them from Europe. Disease did more than cannon and gunfire in the European conquest of the Americas. And the toll on non-human biology was equally disruptive. This happened on our own world. Now it appears we are doing little in the way of planning to ensure we don’t repeat a similar act on Mars.