February 25, 2014 – We know today that CO2 is reaching the threshold of 400 parts per million in our atmosphere. We are told that this component of greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) is the main measure fcr determining human influenced climate change. There are, however, other potent GHGs. One is methane (CH4) and like CO2 it also is studied.

Anthropogenic (that is human produced) methane comes from many sources. These include the mining and burning of fossil fuels, farming, and gases emitted by garbage at landfill sites. It is estimated that 60% of all methane in our atmosphere is derived from human activities.

Methane tends to dissipate much faster than CO2. An average molecule lasts eight to nine years before it oxidizes. That makes methane harder to measure and that’s why methane tends to be measured at the source rather than the way we measure CO2. But are we accurate in our measure? And do we truly understand methane’s contribution to global warming?

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) of the United States, which calculates the amount of methane released through human activity, is being called on the carpet by a recent university study that appeared in a November 2013 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. It appears that the EPA has seriously underestimated the amount of methane released through human activity in the United States. In fact total amounts appear to be between 1.5 and 1.7 times higher than EPA figures.

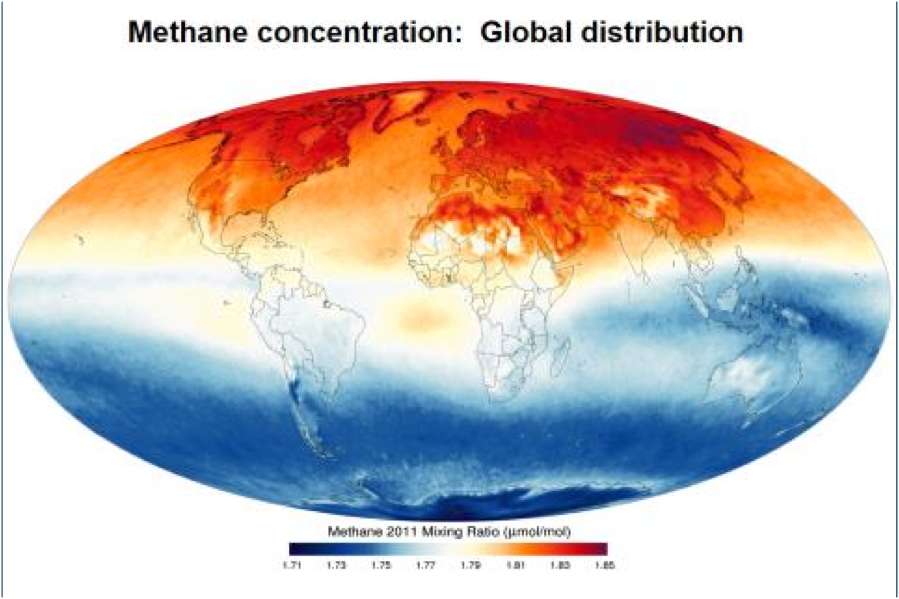

The miscalculation may be the result of different methods used to collect data on the GHG. The study summarily dismisses EPA data and that provided by the European Commission’s Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research, known in short as EDGAR. The data the EPA and EDGAR provide look at source emitters of methane. For example they have a calculation for the average yield of methane from rumination per head of cattle, or the average amount of aerated gas from oil and natural gas wellheads, or the amount emitted from coal mine operations or landfill sites. The study results do not approach the measure of methane this way. Instead the approach is top down, measuring the total concentration of methane in the atmosphere in similar fashion to how we measure CO2. But because methane oxidizes in a short period of time the amounts vary by year considerably.

If both U.S. and European oversight have got it wrong, what about the rest of us studying methane on the planet? What other countries and continents are taking measure of methane output? How consistent is the methodology?

Well it appears that some countries are very much aware of the methane contribution of their dairy and non-dairy cattle. Some are measuring methane output as well from pig farms. Others are measuring methane from fracking wellheads. Some are collecting methane captured from landfill sites. But it appears the measure of methane seems largely dependent on national or institutional preference.

How about the remaining 40% that is not human produced? Most of that methane comes from plant decay from natural wetlands. But even more of the gas is trapped in permanently frozen soils in the sub-arctic of Canada, Alaska and Siberia. This permafrost may not be so permanent after all. Trending to more significant warming in the Arctic may eventually lead to significant amounts of methane release over the coming decades. And although methane does not have the staying power of CO2 it will further destabilize our climate.

The global community, therefore, needs to understand just how much methane we humans are producing and find ways to lessen those amounts. We know that methane has increased in the industrial age. We know this increase is anthropogenic. And we know there are ways we can reduce methane release. Some of these are:

- Breeding new varieties of cattle and dairy herds that emit less methane gas.

- Similarly creating less methane producing pigs.

- Capturing methane gas from fracking sites rather than trying to consume the gas through flaring it off at the wellhead.

Addressing the natural release from permafrost, however, is a much tougher assignment for which there appear to be no easy solutions. And if we should start mining methane hydrates from the ocean floor we could be opening a Pandora’s Box.