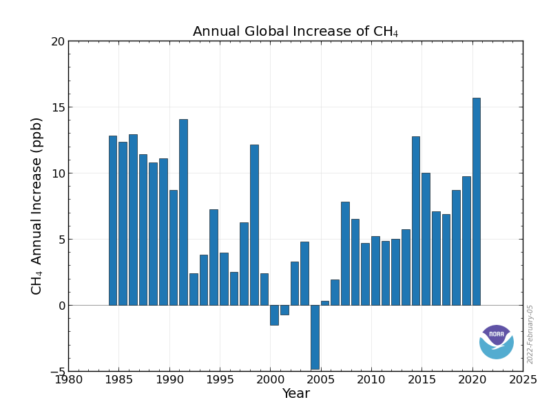

Methane (CH4) levels are spiking off the charts, rising at a much faster rate than carbon dioxide (CO2) and alarming scientists studying climate change. Since 1984 when the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) began tracking CH4 globally, concentrations of it have resembled a rollercoaster ride when plotted graphically. In 1984 the increase in CH4 that year was 12.8 parts per billion (PPB). In 1991, the levels dropped as they did around 2000 and 2004-5. But recently they have been increasing annually (see the chart below).

The latest data from October 2021 shows global monthly means reaching 1,907.2 PPB. The uptick has been steady with current levels triple those from the pre-industrial period. How do we know what those pre-industrial levels were? Through the analysis of ice cores taken from Greenland, scientists have measured the concentrations of gasses in trapped bubbles giving us a record of both CH4 and CO2 levels and how they have changed over 2,000 years.

The latest data from October 2021 shows global monthly means reaching 1,907.2 PPB. The uptick has been steady with current levels triple those from the pre-industrial period. How do we know what those pre-industrial levels were? Through the analysis of ice cores taken from Greenland, scientists have measured the concentrations of gasses in trapped bubbles giving us a record of both CH4 and CO2 levels and how they have changed over 2,000 years.

What could be causing the recent rise?

The likely source of rising CH4 levels one would think is coming from the fossil fuel industry. But that appears not to be the case according to some scientists who are looking at the volume of radioactive carbon isotopes found in sampled gasses. CH4 molecules contain both stable and radioactive carbon isotopes. The two most notable of the latter are carbon-12 and carbon-13. They are analogous to a more well-known radioactive carbon isotope, carbon-14, which if you remember from studying ancient history in high school, has been used to date archeological, anthropological, and other historical remains and findings.

Those Greenland ice cores show an interesting pattern in the percentage of isotopes found in the trapped CH4. Since the Industrial Revolution, they indicate an increase in carbon-13 over carbon-12, that is, until the last fifteen years when carbon-13 started decreasing. Scientists conjecture that the current CH4 spike coinciding with carbon-13 decreases indicates microbes may be the principal source for the increase, and not oil and natural gas operations. In fact, NOAA scientists working at the Global Monitoring Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado, have estimated that 85% of the recent growth in CH4 levels is microbe related.

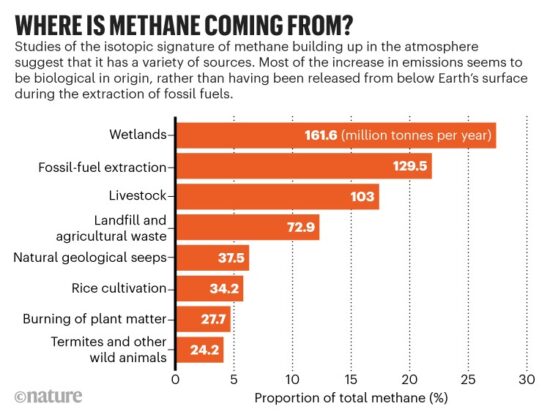

Where are these microbes located? In the gut of livestock, in wetlands, landfills, in cultivation (particularly rice the world’s largest staple crop), wild and controlled plant matter fires, and wild animals. The histogram below breaks down the major suspects and their contributing shares.

But fossil fuel extraction doesn’t get off the hook that easily despite the NOAA report. Another data source comes from satellites, and last week the journal Science published a report that points to human oil and natural gas extraction and production as the prime culprit. The data collected comes from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-5P satellite which has the ability to measure CH4 levels in the atmosphere daily and spot the contributing sources. The data collected shows that two-thirds of CH4 emissions are coming from oil and natural gas extraction and production. The remaining one-third is being emitted by coal, agriculture, and landfill sites. The biggest leaks of the gas are coming from malfunctioning equipment and pipelines. Levels of the gas in some areas are so high, for example, the Permian Basin in Texas, and the oil sands in Alberta, Canada, that the satellite cannot pinpoint which of the fossil fuel operators are the most egregious leakers.

The two aforementioned published reports have surprised me for what they didn’t mention – melting permafrost. Permafrost, found throughout much of the Northern Hemisphere north of 60 degrees latitude, has historically been a carbon sink. But not anymore. The permanently frozen ground in the Arctic is now impermanent and thawing. What is leaking out is largely CH4 with smaller amounts of CO2. Could permafrost be the big contributor to the spike? Based on sampling from Siberian sites, more carbon-12 than 13 is found in melting permafrost samples. So maybe that is an additional biogenic source of rising CH4.

Why are we looking at CH4 when the vast majority of literature on anthropogenic climate change talks about CO2? The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency site includes a considerable amount of information comparing the two greenhouse gasses. It states that CH4 represents about 10% of the country’s overall greenhouse gas emissions but goes on to add, “pound for pound…is 25 times greater than CO2.” That’s why eliminating CH4 would be a climate game-changer. Plugging up CH4 leaks in fossil fuel operations seems comparatively simple, certainly far easier than trying to tackle microbial emissions of the gas.

Last year in Glasgow, at the COP 26 climate conference, 111 countries, representing almost 50% of anthropogenic CH4 contributions agreed to reduce emission by 30% by 2030. This global pledge described that meeting this goal would yield a reduction of 0.2 Celsius in atmospheric temperature rise between now and 2050. The effort will almost exclusively come from the elimination of CH4 in oil, gas, coal, and landfill operations. Trying to cut down cow fart-based CH4 will be trickier. And as for permafrost, with Arctic temperatures rising faster than anywhere else, these thawing parts of our planet represent a ticking time bomb.