December 18, 2016 – A new pilot project is implementing a microgrid in a 5-storey Bloomington, Minnesota building. Microgrid or distributed energy generation technology decentralizes how power is generated no longer requiring long-distance transmission. This is a technology capable of functioning autonomously, eliminating the inefficiencies and interdependency of a transmission distribution system.

In Bloomington, the microgrid will power the OATI Microgrid Technology Center seen in the picture below. David Heim, Chief Strategy Officer for OATI, states that when completed the building will be “fully islandable from the grid.” In other words, it will be its own power source using a combination of natural gas turbines, a solar array, wind turbines, battery storage, a diesel backup generator and a utility connection to Xcel Energy, the local grid provider.

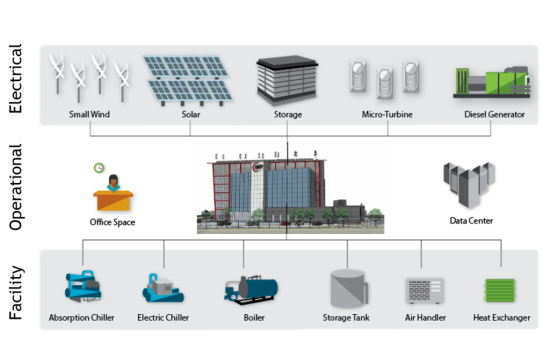

The building houses a data centre and 7,400 square meters (80,000 square feet) of office space, multiple on-site generation sources including a combined cooling, heating and power (CCHP) plant featuring a micro turbine with heat recovery, absorption chillers, a diesel generator, battery storage, solar panels, wind turbines, electrical switchgears to control, protect and isolate equipment against power surges or failures, and an elaborate software control system called OATI GridMind (TM).

The software manages all the available energy sources (see image above), balancing the load, and ensuring reliable continuous power 24 hours a day. It takes account of changing weather conditions which impact renewable production. It tracks external energy pricing to determine the optimal source from which to draw power. It can disconnect entirely from the grid provider, Xcel Energy, drawing solely upon its own power sources. And, finally, it can feed power to neighbouring buildings.

Upon successful completion of the pilot project OATI has plans in 2017 to implement GridMind in big box stores shaving as much as 20 to 30% of energy costs for these retail operators. States Heim, “the future is being able to have a tighter interplay between microgrids, distributed energy resources and utilities.”

The idea of microgrids is an old one. Before electricity the first microgrid, if you can call it that, was the waterwheel providing local power to milling grain. The advent of electrical power in the 19th century soon produced factories with adjoining stand alone power generation capability using coal-fired thermal energy to run these facilities.Until the building of an energy infrastructure in the 20th century, manufacturers continued to generate their own power through microgrids.

By the mid-20th century only isolated mining operations and similar localities generated their own power. The efficiencies of national power grids fuelled by a large network of power stations and connected by transmission lines became a global standard.

No one really talked much about the downside of this technological infrastructure. But in fact transmitting energy across a continent came with an enormous cost. The lines leaked as much as 15% of total energy generated during transmission. The total amount lost in North America alone equals today almost 700 billion kilowatts annually.

In the age of climate change and with interest in developing more sustainable practices, the return of the microgrid is very much at the forefront of urban planners and energy policy developers. Microgrids are seen as a smart answer to produce sustainable power. The challenge for microgrids has been to find a way to manage variable energy production sources in an integrated manner including the storing of surplus power when generated the feeding of it to users through a closed loop system. GridMind is designed to address that challenge.

OATI, GridMind and Bloomington are not alone in pursuit of smart energy microgrids. The city of Adelaide, South Australia, developed MyAdelaideEnergy, part of a zero carbon challenge initiative that hopes to produce microgrid clusters for energy sharing throughout the urban environment. The goal is to recover waste heat, utilize multiple energy generation technologies, and provide off-the-grid power to much of the city.

Another Aussie initiative comes from University of Brisbane where researchers have independently developed software similar to GridMind that acts as a scheduling system for managing energy from variable renewable sources providing load forecasting, discharging and charging schedules.

It is technology like these that will soon turn microgrids from being pilot project exceptions to common urban realities.