When H. G. Wells wrote The Invisible Man, he didn’t have mosquitoes in mind. But that’s what a group of research scientists are trying to do by making us invisible to Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, among a group of biting insects responsible for the spread of Dengue, Yellow Fever, Chikungunya, and the Zika virus.

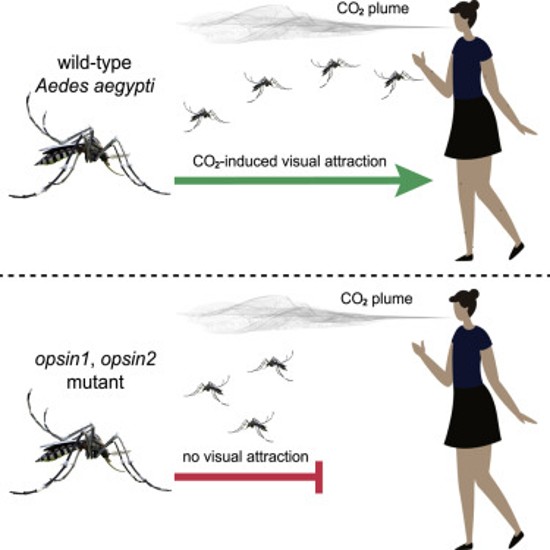

With Aedes aegypti, it is the female of the species that does the biting drawn to us first by visual cues and then as it nears by the exhalations of carbon dioxide (CO2) from our bodies, and by our skin heat and odour. But what if scientists could introduce a mutation that would impede the insect’s ability to see us from afar?

That’s what Yinpeng Zhan, from the Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology and the Neuroscience Research Institute, University of California, Santa Barbara, and Diego Alonso San Alberto, Claire Rusch, and Jeffrey Riffell from the Department of Biology, the University of Washington in Seattle have been working on using CRISPR-Cas9, the DNA editing tool.

Targeting two specific genes, Opsin1 (Op1), and Opsin2 (Op2), of the five responsible for light-sensor receptive proteins, known as rhodopsins, they were able to create genetically modified versions in an experimental group of mosquitoes. They did not tamper with the remaining three genes responsible for vision, or those responsible for olfactory or thermal sensing. The hoped-for result was the creation of a new version of the mosquito less capable of vision-guided flight to target humans. In other words, making us nearly invisible.

Aedes aegypti are daytime biters usually flying in search of prey around dawn and dusk. They use their sight during flight to find targets, and in particular, those that are dark clothed. This visual attraction from afar, when combined with olfactory and thermal cues picked up as the mosquito gets close, serves to navigate mosquitoes to their targets.

Wind tunnel testing of genetically modified females with mutated Op1 and Op2 rhodopsin-protein generators, against a control group of unmodified ones and under varying light conditions, produced results that showed the modified mosquitoes displayed no preference for dark or white targets. That, however, was not true for the unmodified control group that bee-lined to the dark ones.

The mutated mosquitoes’ olfactory and heat receptors remained unaffected, as did their remaining optical sensors. And testing also showed that the mutated mosquitoes could still see, but in flight were less visually perceptive.

Meanwhile, experiments with both mutated and unmutated groups showed equal responses to a combination of black targets in the presence of a 5% CO2 plume. But mutated mosquitoes had no preference for targets, either white or black, in the presence of CO2.

With both mutated and control-group mosquitoes, once they had landed on a target, had no trouble navigating while walking to a place to bite. The researchers concluded that elimination of the normal Op1 and Op2 genes and replacing them with mutations diminished light sensitivity during flight, solely, “below a threshold required for vision-guided target recognition.” Their research appeared in the July 30, 2021 edition of the journal, Current Biology, in a report entitled, “Elimination of vision-guided target attraction in Aedes aegypti using CRISPR.”

What are the implications for humanity? The Aedes aegypti mosquito infects 400 million humans globally and kills more than 700,000, a disproportionate number of them children, every year.