In The Lancet: Planetary Health issue this month, an article entitled, “Projecting the risk of mosquito-borne diseases in a warmer and more populated world,” looks at how the range of these insects has not only expanded but also re-emerged in areas where they had disappeared or subsided for decades. The study creating a multi-model, multi-scenario that looked at the changing lengths of transmission seasons and the human impacts this would have across the planet.

For example, the modelling showed that mosquitoes responsible for spreading malaria would gain between 1 and 6 additional months in the tropical highlands of Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean, and the Americas. And dengue would enjoy up to 4 additional months in the lowlands of the Western Pacific and Eastern Mediterranean.

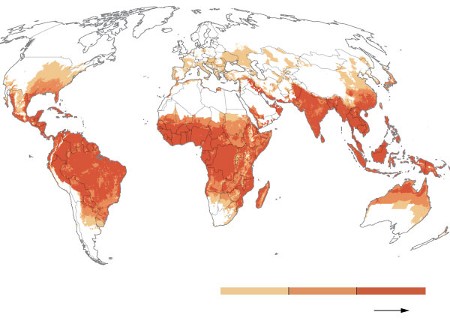

The study concluded that the two mosquito-borne diseases would expand into more temperate areas putting an additional 4 to 7 billion people at risk by 2070. Densely populated urban areas in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Americas would be most adversely affected.

The study noted that today, malaria and dengue are the greatest threat to human health globally with rising temperatures, changes in rainfall patterns, and increased humidity in formerly temperate regions of the planet the greatest influencers on the spread and transmission of both.

The study concludes with the following statement:

“The predicted increases in climatic suitability and population at risk of malaria and dengue highlight the importance of emission reductions to limit climate change and increased surveillance in potential hotspot areas to monitor disease occurrence and plan adaptation interventions in a warmer and more urbanized world. These actions are particularly important in transmission fringes, where public health systems might be unprepared to control and prevent these diseases.”

Global warming has reversed a trend that saw the spatial range of malaria decrease throughout the 20th century. Global incidences of the disease over the past five decades had seen a steep decline. But rising atmospheric temperatures are suddenly reversing the progress we had made in eradicating the disease’s presence.

Meanwhile, dengue has become the fastest-growing mosquito-borne viral disease over the last 60 years. Today it is endemic in more than 120 countries. And what makes dengue so dangerous is that its host, the Aedes aegypti mosquito is found in urban environments during a period when more people are living in cities found in these countries. Rising precipitation in some areas is creating standing water breeding opportunities for the disease’s mosquito hosts. And in rural areas in conditions of drought, the other dengue host, Aedes albopictus, seeks out water storage sites created by humans producing concentrated disease sources.

The study also points out that the spread of both malaria and dengue are horizontal and vertical. Horizontal, because the growth of the geographic area of coverage is expanding (see dengue world map above). And vertical, because the mosquitoes are finding a warming atmosphere makes it possible for them to find a habitat at higher altitudes.

There are three ways to stop this spread.

- Develop genetically modified sterile mosquitoes to breed with the wild population causing it to crash.

- Develop vaccines against both malaria and dengue.

- Mitigate the causes of global warming.

Currently, we are doing more about points 1 and 2, and failing miserably at point 3.