The vaccine research for both adenovirus and mRNA-based vaccines has been focused on identifying the unique S or spike protein that COVID-19 uses to penetrate healthy cells so it can replicate en masse. But if anything is going to change rapidly it is proteins that find new ways to fold in response to changes in the environment. That’s why COVID vaccine researchers need to look beyond the protein to the entire virus from its envelope which encapsulates it to the content inside as it develops new jab candidates.

The latest mutation of COVID-19 has been given the Greek letter Omicron (we skipped Nu and Xi to minimize Mu confusion and the obvious association of the latter name with China’s current leader). Omicron was genetically mapped first in South Africa. It differs from the current dominating variant, Delta, because it has a large number of new mutation characteristics.

The scientific name for Omicron is COVID-Sars2-B.1.1.529. Its spike protein has 30 new variations differentiating it from Delta and other previous versions of the virus. Some of these differences can be found in Alpha and Delta and what has raised concerns is that the differences are linked to increased infectivity and antibody avoidance characteristics for the virus. It goes beyond antibody avoidance because initial study suggests this evolved variant can dodge our T attack cells that are a critical component of the body’s immune response.

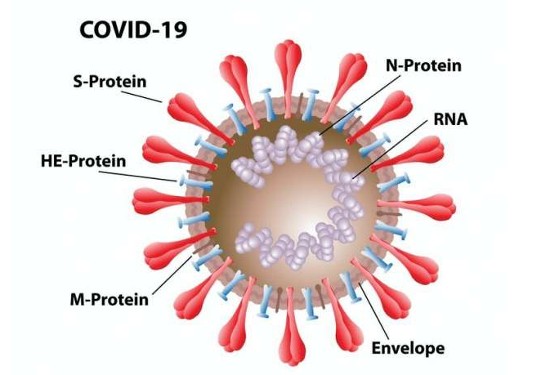

COVID-19 has four different proteins of which the spike is one. The spike in the diagram below is designated S. The rest are N, HE, and M.

The latest research shows our natural immune system reacts to all four proteins, but less to the S than the N, the latter which is found inside the virus capsule wrapping around its RNA core. The problem is that the S is the vehicle of entry and the N is only seen after the horses have left the stable and seeded other healthy cells with more viruses.

Knowing that the N is more visible to our immune system than the other proteins should give vaccine developers a brand new tool with which to work. By adding N-protein antibodies to new vaccines we can enhance them and the body’s immune response. The added benefit to such a strategy would be that, with N common to many other coronaviruses, unlike the spike protein, it would make a new generation of vaccines truly multivalent.

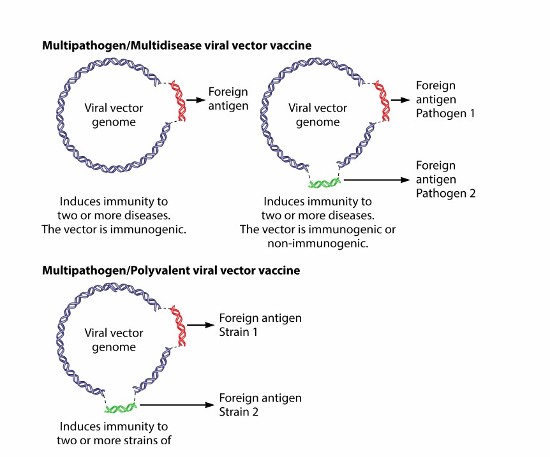

Multivalent vaccines deliver multiple antibodies and can provide lifetime protection for a range of viral infections. These vaccines combine treatments for several diseases through a single course of jabs. Think measles, mumps, and rubella, the multivalent vaccine most commonly used today and you get the idea.

In this case, a new multivalent vaccine would recognize all COVID-19 variants, and all the other coronaviruses responsible for illness in humans. Just in case you didn’t know it, we have been dealing with coronaviruses for a long time. The U.S. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention lists four responsible for upper-respiratory-tract infections similar to the common cold. We have learned to live with 229E, NL63, OC43, and HKU1, all airborne, close-contact, or surface transmitted viruses that are prevalent every fall and winter. Today we treat these infections with home remedies. A multivalent mRNA vaccine that tackles COVID-19 would also eliminate these other seasonal coronavirus infections. Better still, a multivalent or multi-disease mRNA vaccine could target more than just coronaviruses. A new lexicon of terminology describes these future treatments which include:

- Multivalent/polyvalent vector vaccines – combining different strains of one pathogen, for example, COVID-19 into a single vaccine to eliminate that disease in all its variants exclusively.

- Multidisease/multi pathogen vector vaccines – combining the treatment of two or more pathogens through the administration of a single vaccine to eliminate several diseases.

How they work is well illustrated below.

So in the next decade could we be seeing new candidate vaccines not only to tackle COVID-19, but HIV, malaria, and other viral infections? Biopharmaceutical companies and researchers in universities and hospitals around the world are working to make this a reality.