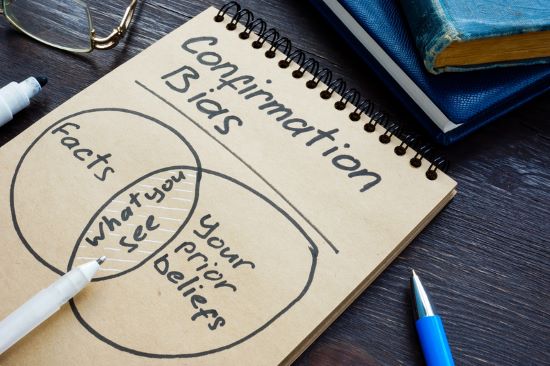

I seek evidence and facts when I write about science, technology, society and the future. Sadly, that is not the case for most humans when processing information. We bring a lot of baggage to the table each time we listen to an argument, read an editorial opinion, or everyday news that describes what is happening in our neighbourhoods and country.

Our baggage contains cognitive biases, dissonance, emotional attachments, and belief perseverance inherited from our upbringing and historical and cultural roots. Facts, when presented, just don’t cut through the fog.

Let’s look at current and recent events as examples of where cognitive bias and belief perseverance are playing out on the world stage.

- Climate Change skeptics question the science from an ideological framework that describes the science and those who advocate it as having hidden agendas. Their cognitive biases cherry-pick data to support their views, and they misinterpret and misrepresent findings to support pre-existing biases. They use economic arguments to support doing nothing because action is expensive and unaffordable. Or they suggest that climate change will be beneficial well into the future.

- Bitcoin as an alternative currency is heavily shaped by cognitive biases and belief perseverance. Herd mentality owns the cryptocurrency space which is fuelled by fears of missing out on a sure thing. That’s why Bitcoin fluctuates in value so dramatically. Bitcoin is viewed by those who buy into it as digital gold without understanding the technology that underlies it. Media coverage enhances herd behaviour and what some call irrational exuberance when Bitcoin rises and panic when it suddenly falls. I have referred to Bitcoin as an elaborate Ponzi scheme. That’s my bias based on looking at historical equivalents like the speculative frenzy in the 17th century Netherlands involving tulip bulbs, or the South Sea Bubble in the 18th century United Kingdom that happened with the collapse of the South Sea Company after fleecing tens of thousands by selling worthless shares.

- Our views of the current crisis in the Middle East are seen through lenses of cultural bias, emotional attachments, and beliefs. For those not on the sites where the Israel-Hamas, Israel-Hezbollah, Israel-Houthi, and Israel-Iran confrontations, we are largely subjected to secondhand information that contains bias or is incomplete. We are influenced by images that spark emotional reactions when we have always known that war produces hell on Earth wherever it springs up. We don’t invest in understanding the history from the combatants’ perspectives. Our biases may come from a perspective based on oil politics, the legacy of European colonialism, Jewish history related to antisemitism and the Holocaust, and Palestinian history before the establishment of Israel and since.

- The election of the next U.S. President brings out cognitive dissonance effects. Americans have increasingly shown strong emotional attachments to their respective political parties, Republican and Democrat. They see the other side as being close-minded, dishonest, immoral, and unintelligent and in the act of voting their polarization contributes to an amplified divide. Each side persists in living within its echo chamber of news, viewpoints and “alternate facts” that cognitively reinforce their views. This is being enhanced by social media and the use of artificial intelligence to reinforce messaging that appeals to an emotional and visceral response. The biases are self-reinforcing making it harder for the national government to be effective and as a result, making a strong-man narrative more appealing to some.

So how do you overcome resistance to facts? I asked an AI what it would do and this is the list it provided:

- Provide an “out”: Give people a way to change their minds without feeling they were entirely wrong before.

- Build empathy: Understand the underlying reasons for someone’s beliefs and address those concerns.

- Avoid belittling: Ridiculing or ostracizing people for their beliefs often backfires, causing them to dig in further.

- Present information carefully: How facts are framed and the context in which they’re presented can significantly impact their reception.

- Engage in constructive dialogue: Instead of simply presenting facts, engage in open and respectful conversations that allow for mutual understanding and exploration of ideas.

When Elizabeth Kolbert wrote about why most of us find it hard to budge from our biases back in 2017, in the New Yorker, she looked at some scientific studies that linked counterfactual behaviour to evolution, the limitations of our reasoning abilities, and our blindness to cognitive, confirmation and cultural biases.