The International Space Station (ISS) is expected to reach end-of-life circa 2030-31. That’s because the modules used to build it are showing their age.

Ask NASA how much time crews spend weekly on maintenance and you get a variety of answers. In a 2006 report, it said that crew members spent 1.8 hours daily on maintenance. A more recent answer noted that when the ISS is down to a complement of 3 crew members, 100 hours weekly is spent on maintenance. Divide that by 3 and then 7 and you get 4.75 hours daily.

Compare that to 160 hours spent weekly on doing scientific research and you can begin to see that the ISS, without significant refurbishment, will soon be like an old car. Do you continue to maintain it or replace it?

NASA and its ISS partners have faced several choices.

- Move the ISS to a higher orbit and then mothball it for possible future use while replacing it with commercial station alternatives.

- Continue to operate it indefinitely at an annual cost of $350 million not including crew exchanges which increase the total cost to $3 billion.

- Replace parts of the ISS structure that warrant it with commercial and non-commercial modules which would come in at a fraction of the cost of putting a new station in orbit.

- Deorbiting the ISS.

- Wait for one or more of the commercial space station projects in design or partially constructed to make it into space before 2030.

The NASA Deorbit Option

NASA is placing its bets on doing the last two options and in response to a deorbiting request for proposal selected SpaceX to do the job for $843 million. That’s right! To destroy the ISS. the U.S. will pay Elon Musk’s company nearly a billion US dollars.

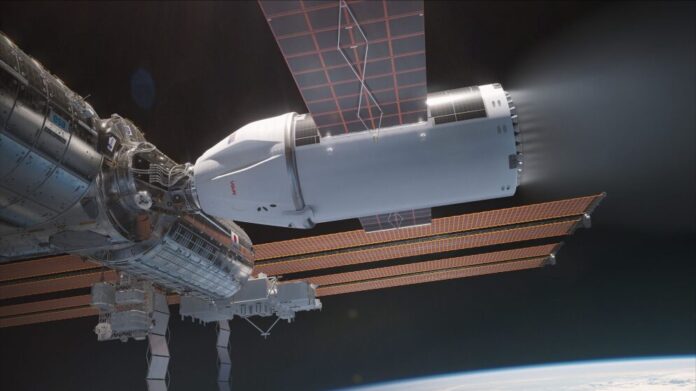

The plan isn’t to use the SpaceX Starship to tow and direct the ISS in its plunge into the Southern Pacific Ocean far away from land. Instead, the commercial space company plans include a modified Dragon spacecraft with more horsepower to get the job done.

The vehicle is called the Dragon USDV. The acronym stands for United States Deorbit Vehicle. It will have an extended chassis or trunk which will carry 600% more propellant and feature 28 more Draco thrusters than the current 18 on Dragon today. The extension will be powered by a solar array and store up to 4 times the energy used for Dragon crew and resupply missions.

A Dragon USDV will launch probably using a Falcon Heavy to get it to the ISS. A Dragon crewed mission will shortly follow. The crew will prepare the station for deorbit and then depart. The ISS orbit will be allowed to degrade naturally until it reaches 330 kilometres (approximately 205 miles) above the Earth. The Dragon USDV will then fire up its thrusters to begin a controlled drop aimed at a 2,000-kilometre (1,200-mile) window in the Pacific. The Dragon USDV and most of the ISS will burn up. Some will stay intact with pieces as big as a car hitting the water.

I don’t know about you, but I don’t get it. Currently, the ISS costs $350 million annually with or without crews. That’s almost $500 million less than the deorbit project cost. Couldn’t the ISS use existing Dragon, Soyuz, Progress and Cygnus resupply and even Boeing Starliner modules to boost it to a higher orbit for mothballing at minimal cost make more sense? Then modules worth saving and other pieces of ISS infrastructure could be cannibalized for future space projects. Even if and when commercial station replacements get built and launched, couldn’t some use pieces of the ISS to speed up completion or enhance their projects?

A Status Check on Current Space Station Projects

Besides China’s current space station, Tiangong, what is the present state of planning for future low-Earth orbit habitats?

Russia Orbital Station (ROS)

The Russians have been significant partners in the ISS. The war in Ukraine, however, has created a falling out between the Russian space agency, Roscosmos, NASA, and the European Space Agency (ESA). Roscosmos, therefore, has other plans, to build and launch a separate station the Russian Orbital Station (ROS).

The plan is to put this new low-Earth orbit station 400 kilometres above the planet in a near-polar orbit which will serve Russia better for surveying its terrain. The first of four modules is to be launched in 2027 subject to having the launch capability. The remainder will follow in staggered launches through to 2033. First crews will occupy the station as early as 2028. ROS is estimated to cost 608.9 billion rubles (USD 6.98 billion).

Does Russia have the means and money to achieve its plan for ROS? Russia has been challenged by a lack of launch capacity. Its Soyuz rockets can handle Soyuz-crewed modules and Progress resupply ships. But building a reliable successor to its Proton heavy-lift rockets has been fraught with challenges. Roscosmos has been working on the Angara A5 heavy-lift rocket for more than a decade. First launched in 2014, it has had three successes and one partial failure.

Then there is Russia’s belated departure date from the ISS. It keeps moving. When originally announced, Russia was to be gone by the end of 2024 or in 2025. Now it appears 2028 is the end date coinciding with the launch of the first ROS module.

Current Status of the Axiom Space Station

I have previously written about Axiom Space in partnership with Thales Alenia. It has always claimed that it will be the first commercial space station operator, albeit it will do this by mating itself to the ISS to start with plans to separate later.

The completion and launch of its first module is scheduled for sometime in 2025. Beyond that, Axiom intends to add three more before the ISS is decommissioned in 2030 to decouple and operate as a destination for future crewed space missions.

The four modules planned include:

- Ax-H1 is on target to be launched in 2026, a dedicated crew quarter with adjoining research and manufacturing facilities.

- Ax-H2 to follow will be an extension of Ax-H1 providing increased capacity.

- Ax-RMF will be a dedicated research and manufacturing laboratory

- Ax-PTM will add extended life support and increased storage and payload capacity to make the Axiom Space Station self-sustaining.

Current Status of Orbital Reef

Orbital Reef is a joint space station project headed up by Blue Origin with Sierra Space, Boeing, Arizona State University, Genesis Engineering Solutions, Amazon Web Services and Supply Chain, and Redwire Space all partners. It is described as the first open-system architectured space station with the first modules to be deployed before 2030 when it will be operational in full as a replacement for the ISS.

The two latest milestones achieved in the designing of Orbital Reef is a successful test of its life support systems by NASA. This has been followed by a successful burst test this last week at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, of the Sierra Space-built LIFE habitat structure where crews will live and work when the station is deployed.

Current Status of Starlab

Starlab is a joint venture involving Voyager Space, Airbus and Northrop Grumman. It will be a continuously crewed space station that has achieved multiple milestones this year. Its target deployment date remains 2027.

Current Status of Haven-1

Haven-1 is Vast Space’s entry into the commercial space station market. The first non-inhabitable module is to be followed by a crew-capable addition offering both micro and lunar artificial gravity environments. Vast has entered into a partnership with SpaceX for the launch of subsequent modules to create what will first be a Starship-class module followed by the Artificial Gravity Station, a space station that eventually will rival the ISS in size. It is designed to rotate around a central docking port.

Last April, Vast announced that the Haven-1 is to be equipped with a Starlink laser terminal to provide Gigabit per second connectivity from it to Earth for future occupants. If all goes well SpaceX will launch the first Haven-1 module on a Falcon9 in 2025.

A Final Word

Are there other commercial space station deployments on the horizon? More than likely there will be as commercial space station operations deploy and begin to turn a profit for companies that use these off-world facilities. We’ve only seen European and American entries in the commercial space so far. I suspect, however, that besides China and Russian national programs and private companies, we will see commercial partners from Japan, South Korea and India’s ISRO joining the space station race in the mid-2030s.

The proof of commercial space station success remains to be seen with the first launches scheduled for next year and several more to be deployed in stages before the end of the decade. Maybe then we can say goodbye to the pioneering station, the ISS that provided proof that humans could make a go of it inhabiting near-Earth space over long periods.

[…] is even flying private missions with Dragon, and a version of the spacecraft will be used in a future mission to deorbit the space station sometime after […]