November 21, 2019 – With the speed limitations of chemical rockets, the current propulsive technology we have to get to Mars, a crewed journey would take at least six months to get to the Red Planet. That means along with the crew would come a payload of consumables for the outward bound trip, the stay on the surface, and the return to Earth. That means lugging the food, water, oxygen, and fuel for a mission that NASA estimates would last at least three Earth years.

NASA has been considering this challenge for sometime. You can read about the consumable requirements for a crew of four on a mission to Mars on their site. The food alone over the duration would eqaul 10,886 kilograms in weight. Water usage is calculated at 11 liters (approximately 3 U.S. gallons) per person per day. Some of that could be saved through recycling technology currently onboard the International Space Station.

But unlike NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) is looking at hibernation as a way to reduce the consumable requirement for a mission to Mars. Through the controlled use of torpor and hibernation, an astronaut’s metabolic rate would lowered to put he or she into a sleep state which would conserve oxygen, water, and food, and at the same time, reduce exposure to cosmic radiation.

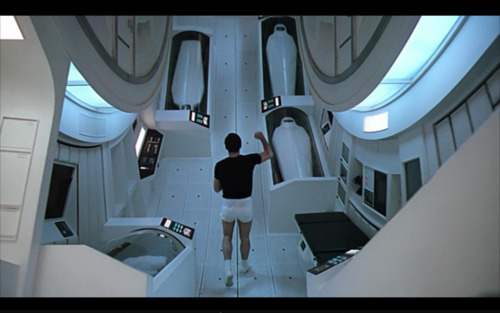

The Concurrent Design Facility (CDF) at ESA has been tasked with developing hibernation technology and designing a spacecraft for the journey that would reflect the need for less consumables and physical space. What ESA is hoping to do is duplicate in the real world what we have seen in science fiction movies like “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

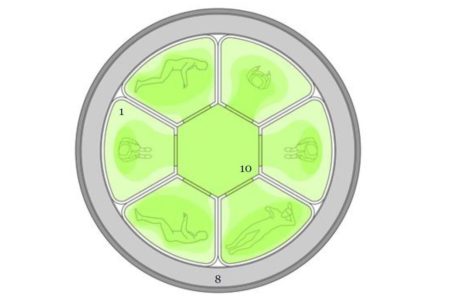

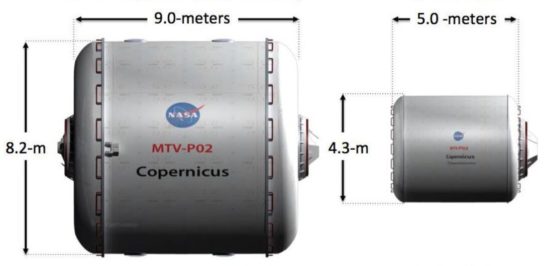

CDF in its planning considerations used a 5-year mission and 6 crew members in its planning of the design of a spacecraft. The habitation module for hibernation can be seen on the right in the image below compared to a non-hibernation alternative, a much larger spacecraft. Hibernation would not only reduce crew quarters’ size but would reduce consumables needed by at least one third for the entire mission.

The technology to induce torpor or hibernation remains a challenge, but according to a new clinical trial at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, this just might be possible sooner than later. What the medical team at Maryland are attempting is a method of dealing with acute trauma by putting a patient into suspended animation. They call the technique, Emergency Preservation, and Resuscitation (EPR). With EPR the body is rapidly cooled to a temperature of between 10 and 15 Celsius (50 to 59 Fahrenheit) by replacing blood with ice-cold saline. This induces a controlled state of hypothermia where the heart stops and brain activity slows to a minimum.

EPR isn’t meant to be used for hibernation but rather is being trialed as a method for dealing with acute trauma where there is a significant loss of blood and little time to get a patient to the operating room. Currently, the limitation in this clinical trial is not to put the patient into a torpor state for more than 2 hours before beginning the body rewarming and restarting of the heart.

States Samuel Tisherman, who is heading up the clinical trial, “I want to make clear that we’re not trying to send people off to Saturn…We’re trying to buy ourselves more time to save lives.”

The EPR process when first attempted was described by Tisherman as “a little surreal,” but if it proves successful, could become the basis for developing prolonged suspended animation and an answer to the challenge of long-duration human spaceflight. Among the remaining unknowns, however, is how an induced torpor would affect brain pathways in the initiation of hibernation and the subsequent restoration of a future astronaut to an awake state.

As ESA sees it in its planning of a Mars mission, the entire crew would be launched fully awake. The hibernation pods would double as crew cabins during this awake phase. Torpor would be achieved through drugs or a process like EPR. In advance of hibernation, the astronauts would be put on diets to increase body fat. The hibernation phase would involve cooling the astronauts to the kind of temperatures in the EPR clinical trial. The hibernation pods would keep the astronauts alive for much of the 180-day Earth to Mars voyage, maintaining a 25% of normal metabolic rate. Only the last 21 days of the transit would involve the astronauts in an awake state. To ensure minimal exposure to cosmic radiation, the hibernation pods would be shielded with water containers.

ESA plans a flight in which the spacecraft would largely operate autonomously using artificial intelligence (AI) capable of detecting faults, dealing with medical emergencies, and managing the voyage in isolation throughout the period of transit. ESA researchers note that hibernation is not such a crazy idea as is being attested by the clinical trial underway at the University of Maryland. Described as a game-changer for trauma, it is likely to become equally useful in keeping astronauts alive and well on trips to Mars and other destinations in the Solar System and beyond.