June 26, 2014 – It will cost $465 million U.S. but the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) will be the first satellite of its type focused solely on observing CO2 levels on Earth. The launch date is July 1st. This is OCO-2 and not just OCO because in 2009 a first attempt to launch an orbiting CO2 monitoring satellite failed.

Onboard OCO-2 are three high-resolution spectrometers to measure atmospheric CO2. Why three? To measure Nadir Mode, Glint Mode and Target Mode.

Nadir Mode views the ground directly beneath the spacecraft. Glint Mode tracks locations where sunlight directly reflects off the Earth’s surface, particularly the Ocean. And Target Mode looks at specified surface targets each time the satellite passes over. The satellite will provide a detailed picture of emissions by scanning 2.59 square kilometers (one square mile) at a time.

Measuring CO2 is in fact measuring how the plant and animal life on our planet breathe as well as measuring our human activity contributions. The Ocean, forests and plants of the Earth absorb about 50% of the 40 billion tons of greenhouse gases added every year through burning fossil fuels, and human industrial and domestic activities. Today, because of the enormous amount we pump into the atmosphere, it takes 1.5 years to absorb just annual CO2 contributions. This is the reason CO2 levels continue to rise.

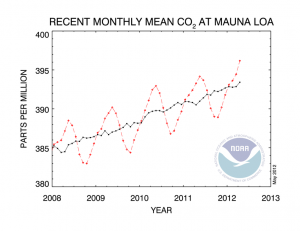

But annually we see a rise and fall to CO2 levels. That’s caused by seasonal changes which impact how CO2 gets absorbed. When winter in the Northern Hemisphere, less gets captured on land and sea, on land because deciduous trees enter dormancy and even the evergreen-dominated boreal forest is less capable of absorbing CO2 at this time of year. Add to this colder water and sea ice in the Oceans and we see as a result higher atmospheric CO2 levels.

Meanwhile the Southern Hemisphere, mostly Ocean, becomes the primary carbon sink during the southern summer. But with less forest mass, the dip in CO2 is not as pronounced as it is when summer returns to the Northern Hemisphere. Hence atmospheric readings of CO2 cycle up and down over the year as seen in the red tracings from data collected at Hawaii’s Mauna Loa site. And because the bulk of the continental land masses lie north of the equator, CO2 expresses its highest levels when winter is in the north.

So if we already know this why do we need OCO-2? The justification is this. The satellite will help identify carbon sinks. It will also give us precise readings of human and natural CO2 emissions across the entire planet. This will give scientists the means to make more accurate projections about climate change.

OCO-2 data will be compared to Japan’s Greenhouse Gases Observing Satellite (GOSAT) which is monitoring methane and CO2. And it will add to the data from ground-based observations currently being conducted by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration which has been measuring atmospheric CO2 since the 1950s.

The OCO-2 mission is budgeted to last two years. Considering the importance of the data it provides we can only hope that it will remain funded well beyond that expiry date.