July 20, 2018 – It wasn’t that long ago that NASA was gearing up to fly astronauts to a Near-Earth Asteroid (NEO), capture it, and bring it back to lunar orbit where it could be studied in depth. This contrived human space mission was supposed to happen in the mid-2020s but saw its end at the expiration of President Obama’s mandate in 2016.

In the Donald Trump era, with Jim Bridenstine, a politician who is neither scientist nor engineer, now in charge of NASA, the agency has set a politically-motivated agenda to return to the Moon and from there to go on to Mars claiming the high ground of space.

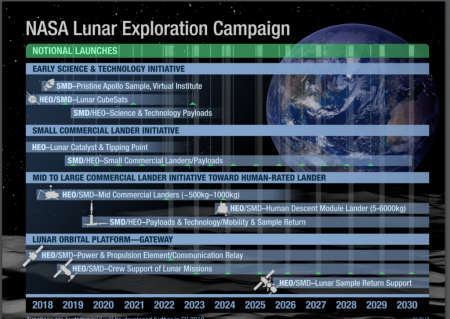

Returning humans to the Moon has been the dream of many in NASA’s astronaut corps. The decision, therefore, is popular in the agency and NASA’s administrators have started putting together a plan to develop new spacecraft and a space station to add to the agency’s Orion space capsule and Space Launch System booster.

The spacecraft needed are ones that will fly in the cislunar space. They will be reusable descent and ascent modules in the tradition of the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM) of the Apollo era.

The Lunar Gateway

The space station program, named the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway, essentially will be a miniature version of today’s International Space Station (ISS). The plan is to place it in an elliptical polar orbit from 1,900 kilometers (1,200 miles) to 75,000 kilometers (47,000 miles) above the Moon. The Gateway will be rendezvous and docking facility for human travelers coming from the Earth, and from those going to and from the Moon.

The Gateway will also serve as a testbed for developing and experimenting with the tools and technology needed to go further into Deep Space, in other words, to get to Mars. More than likely a similar Gateway will eventually orbit Mars.

Of course, on NASA’s current $20 billion annual budget, none of this is possible. And even if commercial space companies were to get involved they would be looking for NASA contracts to fulfill on the deliverables the agency will need to fit all the mission pieces together.

This Gateway is expected to be about one-sixth the size of the existing ISS. Some speculate that ISS parts may be flown to cislunar space to be used to build it once the existing station is decommissioned in the mid-2020s.

Right now the likely structures will include:

- Two school-bus sized habitation modules

- One power and propulsion module

- One or more docking ports

- One or more airlock modules

- Lots of solar panels

- And a propellant fueling station

The docking port will be universally adapted to allow almost any commercial or other space agency’s spacecraft to dock with the Gateway. It will initially accommodate between 4 and 6 humans at any time. The polar orbit would be most advantageous to humans wanting to go to the Moon’s surface because from that perspective they can reach anywhere on the lunar surface including the side we never see from Earth (the Moon is in tidal lock and always presents the same face to observers here on the ground).

The ISS cost $150 billion to make. The Gateway, being more remote and having learned from ISS construction, should cost no more and possibly considerably less. Commercial alternatives to the aluminum canisters of the ISS, may prove to be the better way to go for Gateway construction. For example, using Bigelow’s inflatable modules of which is currently attached to ISS, can be launched in a small volume package and upon arrival in cislunar space be inflated to create substantial accommodation, much bigger than two school buses.

So when will this all happen? Right now the NASA budget for 2019 has assigned over $4.5 billion to Deep Space exploration systems. And budgets for 2020 through 2023 amount to nearly the same annually. If we go by the 2023 budget, money for the Gateway which could cost $150 billion when completed will be in such short supply that the likelihood of it being built within the decade is virtually nil.

The Space Launch System

Today NASA’s non-science program budget is being eaten by two big-ticket items of which the biggest is the Space Launch System (SLS). The ISS annual cost represents a paltry $2.9 billion while SLS has cost since inception in 2004, nearly $18 billion. Just firing one a year adds between $1.5 and 2.5 billion to the NASA budget.

So what is the SLS? Designed to replace the Saturn V rocket behemoth of the Apollo era, the SLS is an old-style monster liquid-fuel rocket that is not reusable. It serves one purpose, to launch to orbit or beyond huge payloads out of the gravity well that is our Earth. NASA describes the SLS as its ticket to Mars. But others have their doubts including veteran astronauts like Canadian, Chris Hadfield, who sees chemical rockets as a dead-end solution to interplanetary travel. Hadfield argues that SLS is just a bigger version of the technology that took us to the Moon in 1969. Using it to get to Mars would be suicide for the astronauts according to him. There is nothing appreciably new about SLS. It is just a bigger version of the Saturn V providing incrementally more horsepower to launch bigger payloads. But for a journey to Mars states Hadfield, the SLS with an Orion payload on top would be equivalent to crossing the Atlantic Ocean in a canoe.

The Orion Exploration Vehicle

The last of the legacy pieces from the Bush and Obama eras is Orion, a space command capsule that supposedly will be a successor to Apollo and meet Deep Space requirements for human crews. Orion was designed initially for a different rocket, not the SLS. Its crew module can carry four into Deep Space for missions lasting up to 21 days in its simplest configuration mated to an accompanying cargo and logistics module. It is outfitted with the latest communications, safety, radiation, and life-support systems. And when mated to a complex of other modules can become the bridge of a spaceship for longer missions of up to 1,000 Earth-days in space. In other words, Orion is NASA’s choice in a voyage to Mars and back.

An uncrewed test of Orion and the SLS is currently slated to happen sometime in 2020. It will take Orion to the Moon where it will enter orbit about 100 kilometers (62 miles) above the surface. It will then do a maneuver to attain a retrograde orbit 70,000 kilometers (40,000 miles) above the Moon where it will stay for six Earth-days. After that, a close flyby combined by engine firing will insert Orion into a trajectory back to Earth were it will splash down in the Pacific Ocean. Total elapsed Earth time will be 21 days.

The building of the Gateway will follow so that a future Orion with a crew of four aboard will dock with it and begin the planned return to the Moon by the mid to late 2020s. The Moon is a good objective for NASA to re-engage. Missions to it will teach the agency about its planned technology and its limits. It will also be a good test for human crews who will for the first time since Apollo be exposed to the hazards of Deep Space. The leap to Mars will be a whole different ballgame.