August 2, 2014 – Fossil fuels have been so convenient as an energy source for us for more than a century. Less messy than coal, able to be distributed through pipelines from the source to consumer, and providing a high energy return on investment. We’ve been pumping them out of the ground since the mid-19th century, finding new uses for even their throw away liquid and aerosol byproducts like gasoline and methane. Before the internal combustion engine all gasoline was good for was as a solvent to clean rusty tools. Now it is almost the reason for the industry’s existence.

Of course there has always been a recognizable downside to fossil fuels – spills. But with so much of fuel around spills have always taken a back seat to drilling and exploiting the resource. But an unrecognized downside, carbon emissions, is altering our dependence on fossil fuels. And because fossil fuels are being found today in less accessible places, the technologies we bring to bear to find and extract them come with increasing risk. That risk was no more obvious with Deepwater Horizon and the BP oil spill which began on April 20, 2010, capped almost three months later, and responsible for spilling 4.9 million barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. The response to this spill is our first story today.

Dispersants from Deepwater Horizon Remain in the Environment Four Years Later

Did you know that in attempting to clean up the oil from Deepwater Horizon, besides the skimmers and booms and other technologies deployed, more than 6.8 million liters (1.8 million gallons) of dispersants were released to break up the slicks that coated the Gulf? And residue from those dispersants, chemicals that contain ingredients found in laxatives, is still being found in the tar balls that wash up on Gulf Coast beaches.

BP and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency had reported that chemical dispersants evaporate leaving little to no residue. But the scientists at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute and Haverford College in Pennsylvania, have proof that is not the case. Their report appears in Environment Sicence & Technology Letters and states that samples from corals, sediments and beach sites continue to contain the dispersant, dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate or DOSS, although in low quantities. The long term impact from the chemical on the biology of the Gulf remains an unknown. A BP spokesperson when asked about the report stated the residual dispersant poses no risk just like deep water drilling poses none as well.

Steam Injection Ruled the Cause of Northern Alberta Oil Sands Spills

A form of fracking using injected steam is named as the cause for the Northern Alberta bitumen leak reported in July of 2013 by this blog site. The spill described as an underground blowout began in April 2013. The oil sands operator, Canadian Natural Resources Ltd. (CNRL) repeatedly assured the Alberta Energy Regulator that the spill was contained. But it was not and is to this day not.

And now we find out from a review panel report that the method employed in steam injection caused five fractures (one as early as 2009) with the bitumen erupting in areas as much as 12 kilometers from the original fracking site. It appears the fractures penetrated what was considered to be an impermeable layer of shale leading to the bitumen dispersing into groundwater and erupting as much as a half kilometer (more than a quarter mile) from the targeted position.

This operation has spilled more than 12,000 barrels of bitumen to-date into an area that is difficult to clean up because of its remoteness and the multiple locations where the bitumen has seeped to the surface. Some of it is leaking into a lake.

Cost so far is $50 million.

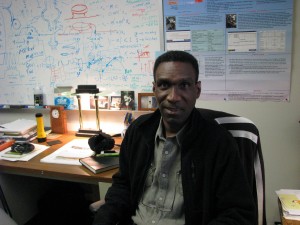

Fermilab Physicist Invents Oil Spill Cleanup Technology

Arden Warner (seen in the photograph below taken by Hanae Armitage) says he gets crazy ideas all the time. A physicist at the Fermilab in Illinois Warner tried a garage experiment taking metal shavings from a old shovel, and mixing them with some motor oil and water. He then used a magnet to attract the oil in which the iron shavings were suspended.

Warner has since received a patent for what may prove to be a breakthrough in oil clean up technology. He has tested his method on more than 100 types of oil and it works with all of them.

In a more refined state than the garage experiment his process involves using magnetite dust dispersed over a spill/ A magnetic field is then applied. The colloid suspension of oil and filings, defined as a magnetorheological fluid, can be pooled to a single location and then removed.

Warner is experimenting with hydrophobic iron filings to improve the extraction efficiency. This type of iron sink into oil right away and doesn’t interact with the water, hence hydrophobic, which makes it convenient when a magnetic field is applied. A magnetic conveyor can be used to pick up the suspension and recover the oil. The oil is then cleaned of the suspended filings and can be fully recovered. And so can the filings which are dried and reused. Want to see a 30-second demonstration? Watch the video.