One measure of progress for any nation is the educational achievements of its citizens. We measure literacy, numeracy, years of public education, post-secondary learning, and more. We equate higher income attainment with higher education. But since the pandemic emerged in 2020, and now into the fourth wave of COVID-19 variants, young people are facing an educational crisis, not of their own making, but one brought on by government policy, and the lack of technological equality.

Here in Ontario, Canada, where I live, the provincial government is responsible for education. Over the last two years, the government has stopped in-classroom learning, delayed the restart of school years, and moved teachers from in-classroom to virtual classroom teaching. It has done this many times coincident with the emergence of new COVID-19 variants and subsequent spikes in general population infection rates. The assumptions the government continues to make are:

- that virtual learning works for all students,

- that access to online learning is ubiquitous.

Both of these assumptions are false.

In an opinion piece that appeared in the January 4th, 2022, The Globe and Mail, Wendy Cukier, Kelly Gallagher-MacKay, and Karen Mundy write, “Little has been done to ensure that students do not face lasting educational and social harms from pandemic disruptions – even as we face the next round of challenges associated with the Omicron variant. The pandemic has disproportionately worsened already significant disparities in educational outcomes for racialized and Indigenous students, as well as those living in poverty or with disabilities. This neglect is setting the stage for a generation with depressed lifetime incomes, increased social inequality and national productivity losses estimated at $1.6-trillion.”

The article describes how this can be prevented through timely social and educational interventions including tutoring, both one-on-one, and in small groups. But that strategy has not been incorporated into the government’s educational policy throughout the pandemic beginning with the first lockdown and continuing to today as we open and close in-class learning in schools. The back and forth of learning paradigms is not just a burden for our youth, but also for parents and educators who have to constantly readjust to these changing realities.

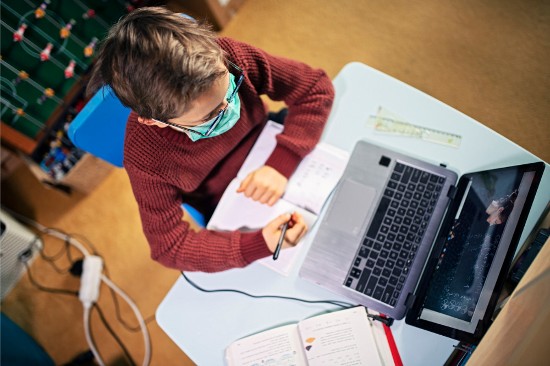

Today in Ontario we are relying on in-classroom teachers to be effective virtual-classroom instructors. The environments for them are as much a challenge as they are for the students they instruct. In-classroom teachers have been learning on the go since the pandemic started on how to be effective in a Zoom-built classroom. At the same time, these teachers are parents of children both pre-school and in-school and dealing with the family challenges that creates. When asked, teachers freely admit that many of their students are struggling to learn online.

That’s why the suggestion made by the authors of this Globe and Mail opinion piece should be taken seriously. They report on a study done by the Poverty Action Lab that describes the effectiveness of implementing tutoring programs in support of public education. The study notes that paraprofessionals who are trained educational assistants working with youth can deliver learning better and at a lower cost than in-classroom teachers working with students online. The report notes that tutoring sessions three or more times a week produces better results from Kindergarten to Grade 12. And although tutoring will add costs to public education, during the pandemic its implementation could produce immeasurable benefits as students catch up in terms of the current educational disparities caused by the pandemic.

What the article doesn’t address is the technology gap. Because of the pandemic, tutoring will largely be online. And here’s where a significant problem lies. Economic inequality and geography make for unequal online learning experiences whether it be an in-classroom teacher or qualified tutor on screen.

Online learning remains a challenge for isolated northern communities in Canada, let alone in Ontario. Access to highspeed broadband services in a study done in 2018 showed that 40.8% of rural households had Internet access with speeds of 50 Megabits per second or better. In First Nations’ communities that number was 31.3%. These numbers may have improved over the last three years, but what they don’t tell you is how many households and communities in these two categories have appropriate computing technology to make online learning work. Trying to learn on a smartphone screen is far different from learning using a desktop or laptop computer with a quality display. And although the federal government of Canada has committed $6 billion to make broadband connectivity available to every Canadian home and business, the date for completion of this project is 2030. That’s well into the future and won’t make a difference to students today who during this pandemic are being disadvantaged by inadequate educational opportunities developed by policymakers who continue to present poorly thought out and badly executed programs.