May 11, 2015 – Replicating photosynthesis has been a dream of scientists ever since humans identified chloroplasts and chlorophyll as the mechanisms by which plants convert carbon dioxide, water and sunlight into food and fuel. Many attempts have been made over the years to mimic what plants do effortlessly and I have faithfully tried to write about these efforts here. Type “artificial photosynthesis” in the search window and you’ll find them.

This quest has remained elusive to date. Either the technology we create in laboratories is too expensive, or the results don’t match the capacity of the plants we are trying to mimic. In plants nature hasn’t created the most efficient process. A typical plant converts energy from sunlight at a rate of 1%. Back in 2012 Panasonic announced that they had matched what plants do using formic acid and a nitride semiconductor and metal catalyst to sequester carbon. But we’ve heard neither hide nor hair about the breakthrough since that announcement which sort of suggests getting it from the laboratory to commercial application has proven more difficult and expensive than Panasonic thought.

Now comes another attempt at doing what plants do. It is out of the Berkeley campus of the University of California. Researchers there have combined bacteria and an array of nanowires to turn carbon dioxide, water and sunlight into “useful organic compounds.” They are not quite saying this is artificial photosynthesis but they predict if they can make it commercially viable it will impact energy production, biopharma and the chemical industry.

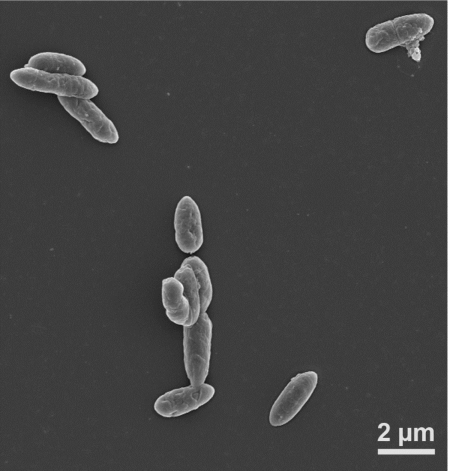

Combining semiconductors with bacteria is a novel approach. The semiconductor nanowires absorb sunlight which gets converted to electrons that are transmitted to a class of bacteria called electrotrophs. I first read about electrotrophs, microbes that interact with electrodes back in 2010 from a research paper published out of the University of Massachusetts. At that time scientists had been experimenting over a decade trying to alter bacteria to accept direct electron transfer. They chose microbes that appeared to be ideal candidates and began experimenting with ways to genetic manipulate them so that an electrode when attached could transfer electrons directly to the cell. The bacteria University of California researchers chose Sporomusa ovata, an anaerobic bacterium (seen below) that demonstrated optimal potential.

One of the greatest challenges to any research into artificial photosynthesis is the presence of the byproduct, oxygen. Plants don’t like it and expel it and we are the happy recipients of that rejection. The bacteria used at University of California is no exception in its distaste for the gas, and although the microbes may be ideal catalysts for carbon dioxide conversion without protection from oxygen the culture would die. The innovation comes in the nanowire matrix which is proving to be a good shield, protecting the bacteria from oxygen’s destructive effect.

Is what these researchers have developed commercially viable? At the moment even they admit it is not. Conversion efficiency is 0.4%, less than half of what an average leaf can do. But in studying the way bacteria and semiconducting materials interact the scientists believe they can develop a synthetic equivalent to bacteria yielding conversion efficiency exceeding 2%. We may be a decade away or more from getting to that level which would be truly revolutionary. We need this type of innovation not only to address the excessive carbon we continue to put into the atmosphere but also to help transition our civilization to a low carbon, energy rich future.