February 21, 2019 – NASA suffers from split personality syndrome. On the one hand, the agency is encouraging commercial space business, while on the other it continues to build a vanity project that has absorbed billions of dollars for more than a decade with no results. I’m talking about NASA’s Human Deep Space project. On the science side, I have no quarrel with NASA’s continuing level of excellence in unfolding the mysteries of our Solar System, the Galaxy, and the Universe. But the human-in-space program is a total bust other than the International Space Station (ISS). Even ISS may succumb to NASA’s misdirected thinking with talk of ending its life by the mid-2020s.

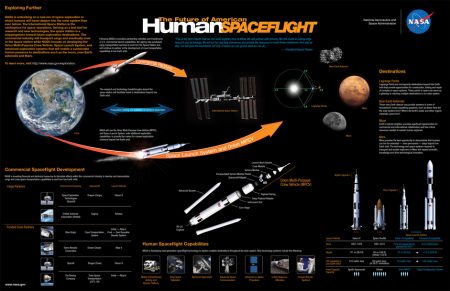

What does NASA have to show for almost two decades of investment in its Deep Space plans? The Orion capsule remains a work in progress, having spent more than $16 billion on it, with one test flight with no humans aboard under its belt. And then there is the Space Launch System (SLS), the enormous single-use rocket that NASA is building to take American astronauts back to the Moon and on to Mars. A colossal ego trip is one way to describe the SLS misadventure which so far has had NASA spend $14 billion with nothing substantial to show for it.

Why has this happened?

The Columbia Space Shuttle disaster in February of 2003 began NASA’s transition away from its human spaceflight program. The Shuttle Program was already a boondoggle with every flight costing close to a billion dollars because reusability, one of the goals of the program, failed utterly. Every launch and return was followed by costly refits. Mounting a spaceplane on the side of a rocket turned out to be a dumb idea leading to not just Columbia’s failure, but also that of the Challenger in 1986.

In ending the shuttle program, NASA went through two restarts. First, there was the Ares rocket and Constellation Program under President George W. Bush. The Orion space capsule was to ride into space atop the Ares rocket while a second launcher would deliver an additional payload to be mated to the capsule in low-Earth orbit. The two would then travel to cislunar space, or to an asteroid, or even eventually to Mars.

When President Obama took office, the Constellation Program was mothballed permanently. Instead, NASA offered a successor to the Saturn V, the SLS. Sold to the government as a solution that would take the best of existing technology already developed by NASA, SLS was supposed to be a more affordable way to get America back into human space flight. But almost everything in the SLS program is new. To build a rocket surpassing the Saturn V in payload capacity, more than forty years after the last Apollo-Saturn mission, couldn’t just be the same thing, only bigger. New manufacturing methods and new materials meant SLS was going to not be just bigger, but also a brand new rocket. Hence significant cost overruns, and flight delays that will now possibly see the first non-crew test flight in 2021.

Where does NASA’s split personality come in?

While NASA has been assembling the SLS and its Orion capsule, it has contributed to the funding of commercial space companies with their own human space programs. SpaceX will launch in early March a reusable Dragon 2.0 capsule atop its partially reusable (first stage only) Falcon 9 rocket. And Boeing, later in the year, will launch its CST-100 Starliner capsule atop a United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas 5 rocket. By year-end, both SpaceX and Boeing should deliver American astronauts to the ISS from the United States for the first time since the last Space Shuttle flight in 2011. Until then NASA will continue to rent a chair or two on Russian Soyuz launch systems to fulfill crew complements onboard ISS.

With commercial space companies added to the mix, does NASA really need the SLS or Orion? The billions of dollars invested in these two projects could be better spent on assisting private ventures developing payload capacity to support NASA’s human-in-space ambitions. In the last two weeks, NASA administration has pledged to put American boots back on the Moon by 2028, and with little in the way of explanation, has described human voyages to Mars in the 2030s. At what cost? No one at NASA is publicly talking about the dollars and cents needed to achieve these two milestones. The administration talks about building a cislunar infrastructure, and a permanent presence on the lunar surface. It waves in front of our noses Orion and the SLS as the delivery vehicle for humans getting to Deep Space.

Who is NASA kidding?

SLS and Orion are make-work projects compared to what will be needed in terms of space infrastructure to make a permanent human presence on the Moon possible, let alone what will be needed for a successful Mars mission.

Every plan involving a human presence on the Moon and Mars includes a live-off-the-land strategy. That is, human crews will have to extract from the Moon and Mars, the necessities of life to ensure their survival. Oxygen, water, hydrogen for fuel, and food will all have to be produced from the lunar and Martian environments.

Technologies to extract resources from the Moon and Mars have yet to be developed to any great extent. The Mars 2020 rover will include a harvester prototype that will attempt to extract oxygen from the Martian atmosphere which is almost 100% carbon dioxide, and tenuous at that. And NASA has been growing plants on the ISS, as well as experimenting with self-contained environmental systems here on Earth where everything gets recycled and reused to make future crews on the Moon, or Mars, or on the long flight to get to and from the latter possible.

Didn’t NASA learn anything from the building of the ISS?

The idea of launching an enormous payload into orbit and beyond justify in the minds of some at NASA the building of the SLS. But NASA, Russia, and a consortium of partner nations assembled ISS in low-Earth orbit sending one module at a time to construct the 450-ton behemoth that is larger in dimension than a soccer pitch.

The rockets and Space Shuttles used to assemble the ISS didn’t need enormous payload capacity. Conceivably, the space infrastructure needed to return to the Moon, and to go to Mars can be built in the same way as the ISS. It may take a little longer but I highly doubt it, considering the many years the SLS and Orion projects have been around and not flown anywhere with anyone on board. And the reusable rocket technology being developed by SpaceX and other commercial space companies could lower the cost of delivery, not only in bringing materials needed for assembly, but also the fuel, oxygen, water, and other consumables required for Deep Space missions.

Partially to fully assembled, a return-to-the-Moon system could be pushed into a translunar trajectory using propulsion systems that NASA has been experimenting with on robotic space missions and that do not require tons of hydrogen and liquid oxygen to move payloads out of Earth’s gravity well.

And for the mission to Mars, the assembly could occur in two stages. An initial number of builds in low-Earth orbit could be transported to cislunar space where these modules could be joined to create a final, more robust Mars spacecraft with greater capacity to ensure the safety and sustainability of human crews on the voyages to and from the Red Planet. NASA should also consider developing and deploying a network of robotic-controlled resupply stations in the space between Earth and Mars that can serve as emergency stops on the journey to and from Mars.

Will NASA end the SLS and Orion programs?

No, because these two programs provide thousands of jobs for contractors and NASA employees who would otherwise leave to go work elsewhere. And once they have left, their expertise would be gone as well. So $3 to 4 billion per each will continue to be spent annually for its Deep Space project while NASA expends far less in using commercial space companies to help it in getting to low-Earth orbit, companies that also have expertise that the agency could use for its lunar and Martian ambitions.