November 16, 2015 – My wife and I are not spending six weeks in Florida this winter. We did this last year but frankly found ourselves bored to tears after a couple of weeks. If I hadn’t had this blog to research and write each day I think I would have gone mad. But reflecting on some of the things I saw in Florida, I wonder what brand of “Kool-Aid” is being drunk by municipalities, property developers and property owners along the coast who continue to ignore the near future of rising seas.

In Fort Lauderdale the city spent millions on shoreline and road restoration after storm surges a few years ago wiped out a large section of A1A, Florida’s coastal highway. They built larger storm drains and raised the seawall one foot higher. That may buy them a couple of decades of peace before rising sea levels and storm surges destroy what they have built. Meanwhile Miami Beach announced building permits for 47 new condominiums along its crowded beachfront to raise taxes to build $300 million worth of sea level abatement projects to try and stop the ocean.

Southern Florida isn’t alone in being in denial. Tyler Hamilton, in this weekend’s Toronto Star Business section wrote a piece called Living on the edge: Housing consequences of climate change. He describes the continuing allure that draws people to own beachfront property and the future risk such investments represent. In a sidebar to the article the following quote appears: “If we continue on our current path by 2050 between $66 billion and $106 billion worth of existing coastal property will likely be below sea level nationwide, with $238 billion to $507 billion worth of property below sea level by 2100.” This conclusion comes from a study appearing in the September 2015 issue of the journal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The above quote brings me back to my morning Florida walks with my pet poodle Maya. Walking along the streets on the seaward side of A1A, called Ocean Drive where we stayed in Fort Lauderdale, I was mystified by the number of lots where new housing was planned. None of these were bungalows set well back from the water’s edge. Instead they were blockbuster homes that came as close to the public beach as possible. Realty taxes on one lot for sale amounted to $60,000 per year. And that was with nothing built on the property. Imagine now adding a multi-million dollar home to the lot that might within a couple of decades be permanently inundated by storm surges and in 30 years be underwater for good.

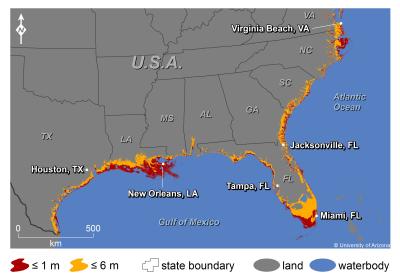

What is happening in Florida is also to be found along the entire East Coast of the United States from the Florida Keys to Maine, and to a lesser extent in Atlantic Canada. And by the behavior being observed it seems even a fleeting ownership of beachfront property means more than heeding the warnings of climate scientists and oceanographers.

In Hamilton’s article he talks about the experience of one town, North Topsail Beach, North Carolina (see picture below), a small beachfront community. When Hurricane Joaquin recently passed by in the Atlantic Ocean its eye was far from North Topsail Beach but that didn’t stop the storm surge, peripheral winds and rain from doing lots of damage. Total cost for repairs so far amounts to $15.5 million U.S. and climbing. This is just one town among almost two thousand coastal communities with tens of thousands of beachfront property owners all under threat. Oceanographer John Englander, author of High Tide on Main Street, a book that predicted the damage Hurricane Sandy inflicted on New Jersey and New York City shore communities, describes the issue as more than environmental. It is economics. He states, “people who own lots of real estate and finance it, they haven’t really thought this through yet.”

And neither have municipal governments who continue to throw good money after bad, bailing out property owners to let them keep their beachfront ocean views, rebuilding piers, restoring beaches and coastal roadways, in a losing battle with the sea. It cannot continue because growing insurance payouts and cost increases will eventually bankrupt communities as they attempt to appease property owners who lose their staircases and docks or watch their beaches wash away. After all these owners pay the taxes that fund municipal government.

Hamilton points out that FEMA’s insurance program, designed to subsidize property insurance in flood-prone zones, is today more than $24 billion in debt just from the damages caused by Hurricanes’ Katrina and Sandy. What will happen as sea levels and storm surges further damage shoreline infrastructure?

One thing some governments are doing is turning a blind eye to scientific evidence. A science panel charged with writing a report for the North Carolina Coastal Resources Commission revised its findings in a 2010 original report forecast an end of century sea level rise of minimally 0.4 meters (15 inches) and maximally 1.4 meters (55 inches) with the consensus pointing to at least a 1 meter (39 inches). The state government asked them to revise the report so that it would be less scary to taxpayers in the state. The 2014 report used a 30-year scenario with a less frightening forecast of a 22 centimeter (9 inch) rise. Neither the original or the revised version took into consideration storm surges significantly increasing water levels. Nor did either version take into consideration accelerated melting from Greenland (as recently reported in the New York Times) and Antarctic glaciers and the combined contribution the two could make to sea level rise.

So what does this mean to coastal dwellers besides the enormous dollars and cents needed to stave off rising sea levels? It is about 20 million or more lives that would be disrupted through personal property losses. The economics of this impending disaster are mind boggling. And yet beachfront property remains a hot commodity.

It seems the New Testament parable to teach us about “the foolish man who built his house on sand” remains ignored or misunderstood in the age of climate change.