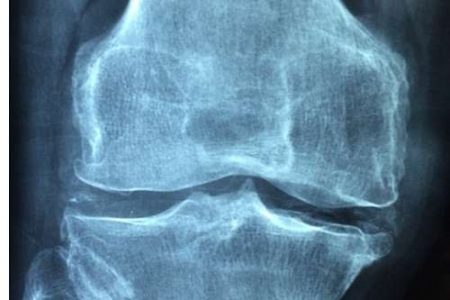

April 14, 2018 – My regular readers may have picked up from time to time my history of knee problems. I have osteoarthritis, a complication caused by an injury I suffered when I was 20 years old. Reconstruction of my left leg after multiple fractures left the foot turned in slightly and over the years that has led to uneven wear of the cartilage in my knee joint. I’ve had consultations, MRIs, multiple x-rays, cortisone injections, and have tried various supplements and painkillers to manage what has been a slow and steady deterioration as the cartilage has worn away.

In my search for non-surgical approaches to restoring my knee function I have looked at research into the use of stem cells, and I have asked one of my brothers who is a doctor, and who has recently undergone partial knee-joint replacement, to look at the state of regenerative medical options available to me. It appears that there is technology today that can take millions of stem cells from my adipose tissue (body fat) around my belly, and re-inject them into my knee joint. In theory, the cartilage would then trigger stem cells to begin replicating as chondrocytes (the cells that form cartilage). But until you can ensure that the regrown cartilage ends up in the right place, stem cell injection therapies for knee joint restoration are purely hit and miss.

To solve the remaining challenge research is being done to develop dissolvable matrices using gelatinous materials that don’t trigger the body’s autoimmune response. Ideally, a 3D bioprinter would create a scaffold precisely shaped using the data from digital MRI and x-ray images. This would serve as a framework for stem cells turned chondrocytes to grow in place and restore the joint. The doctors, aided by precision-guided artificial intelligence would inject gel into the knee joint positioning it to form the scaffolding upon which the stem cells turned chondrocytes would grow. As they did the gel scaffolding would slowly dissolve leaving a healthy, regenerated knee. That’s what I have been holding out for as I search for a better outcome than one that involves removing my knee joint and replacing it with something artificial.

This week, however, I had an outpatient appointment at the Sunnybrook Holland Orthopaedic & Arthritic Centre here in Toronto. My family doctor arranged it after I suffered a fall in our apartment bathroom. I was seen by a resident and occupational physiotherapist. I brought along two recent x-rays of my knee joint and the findings which indicated that I had tricompartmental left knee osteoarthritis. The radiologist report that accompanied the x-rays described by osteoarthritis as severe and worsening based on a comparison of images done in two consecutive years. My immediate thought was, here goes, I’m going to see the orthopaedic surgeon and be told when I would go under the knife.

But that’s not what happened. Instead, the resident took a history. Then I was seen by a team of occupational therapists. One had me doing a timed walking test, followed by a timed stand-up and sit-down test. Then I had range-of-motion, and muscle strength tests to compare my left and right knee function. Overall, despite what my x-rays showed, the occupational therapy team gave me encouraging results. My left knee was performing pretty well despite the loss of most of my cartilage. I would attribute this to daily walks with my dog. But I also found out I was neglecting some key muscles that would make my knee function even better.

I had already resolved to go on a diet to take the weight off the knee joint. And now I am adding swimming, stationary cycling and a series of yoga-like exercises to my routine. The idea is to strengthen hip, thigh, hamstrings and quadriceps to give my muscles greater endurance and improve range of motion in the joint. Losing weight should make the rehabilitation root that much more effective.

So no surgery pending, an outcome for which I would be more than happy. And maybe, while I am rehabilitating my knee joint sans surgery, progress on stem cell regenerative medicine will eventually mean no need for joint replacement in my future. An orthopaedic surgeon my brother talked to on my behalf in the last week says we are a decade away from seeing this technology move from the laboratory to clinical trials, and to become an option for patients with osteoarthritis. Within a decade I will still be in my seventies.

I’m happy to wait.