July 14, 2016 – In the recent Three Amigos meeting involving Canada’s Prime Minister, the President of Mexico and the President of the United States, the leaders announced they were committed to action to drive down short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs). We have been told about carbon dioxide (CO2) and its long-term implications related to global warming. But lost in our focus on CO2 are a number of other anthropogenically-derived contributors to global warming. These include black carbon, methane, tropospheric ozone and hydrofluorocarbons.

Black Carbon – What is it?

When you look at an industrial plant or tail pipe emissions you see smoke. That smoke consists of small particles of which the major constituents are carbon, sulfates and nitrates. Particles vary from as small as 2.5 micrometers (um) to 10 micrometers. If you think about 10 micrometers as a measure that you may better relate to it is equal to approximately 0.00039 of an inch. That’s very small, in fact so small that these black carbon, sulfate and nitrate particles get into our lungs where they can lead to medical problems. In China with its heavy reliance on coal-fired power plants the country faces what has been referred to as an airpocalypse with average lifespans shrinking among its citizens because of respiratory and heart disease attributed to particulate matter.

How does black carbon contribute to global warming? Particles as small as 2.5 micrometers strongly absorb light energy from the Sun which then converts to heat in the atmosphere. In addition black carbon gets moved around the world by air currents and one particular vulnerable location is the Arctic. Black carbon along with CO2 is contributing to accelerated glacial and sea ice melt. The Dark Snow project, a crowd-funded study, is gathering evidence of the role black carbon plays in the shrinking of polar ice. The image below illustrates just how extensive black carbon’s reach can go. Normally this ice would be pristeen and white. But as you can see black carbon delivered by air currents even reaches the remote surface of Greenland ice sheets.

Black carbon has another characteristic. In sufficient airborne quantities it alters precipitation patterns working the same way as cloud seeding. In the case of the latter we shoot aerosols, usually silver iodide crystals, into the atmosphere to induce precipitation. The crystals form a nucleus around which water vapour congeals. Black carbon does exactly the same thing.

Methane

We are all becoming more familiar with methane (CH4) as a potent greenhouse gas in recent weeks because political leaders have raised its profile in the fight against global warming. So why is CH4 such a potent greenhouse gas and how does it differ from CO2? It’s potent because the gas molecule is large and when light strikes it, it has a much higher capacity than CO2. And whereas CO2 lingers for centuries in the atmosphere, CH4 has a limited atmospheric lifespan of 12 years before the molecule breaks down.

Anthropogenic methane comes from a number of sources including:

- fossil fuel extraction and refining – 29% (see photo above)

- livestock enteric emissions (cow farts) – 29%

- waste and wastewater treatment – 20%

- rice cultivation – 10%

- other agricultural sources – 7%

- livestock manure – 4%

CH4 is responsible for about half of observed rise in ozone (O3) within the troposphere. That’s not the O3 found in the stratospheric ozone layer that has been of such concern for several decades because holes have opened. Tropospheric O3 contributes to asthma and respiratory illness. For more on this consequence of CH4 read the section that follows.

Humans and human activities aren’t the only source of CH4. Forests and natural landscapes as they go through seasonal variations contribute CH4 in significant quantity. But before humans started pumping out CH4 there was homeostasis in the environment, in other words, a natural balance that didn’t contribute to global warming.

Another source of CH4 is permafrost which as it thaws releases significant amounts of the gas.

The reason that Three Amigo summit announced targeted CH4 reductions of 40 to 45% by 2025 from the oil and gas sector is simple. Without this initiative anthropogenic CH4 was expected to increase by 25% by 2030. So targeting emissions from fossil fuels makes immediate sense. The real challenge will be CH4 reductions in agriculture.

Tropospheric Ozone

If you live in a city then you have experienced the effects of tropospheric ozone (O3). It is the principle component of urban smog. Also known as ground-level ozone, O3 is the most significant urban pollutant we humans create when we heat our homes, run our smokestack industries and drive our cars.

Have you experienced O3’s impact? You may not realize it but when you walk on a street where the traffic is busy and your eyes start to burn or you nose gets plugged and runny then you are experiencing the O3 effect.

As a greenhouse gas O3 has a short lifetime, lasting no more than a few days to a few weeks. But the damage it does to plants and humans is significant. In plants it reduces their ability to absorb CO2 inhibiting growth as well as interfering with the plants capability to act as a natural carbon sink. And in humans our children experience childhood asthma because of it while adults suffer with lung and cardiovascular complications from it. O3 has been cited by scientists as responsible for an estimated 150,000 premature deaths annually.

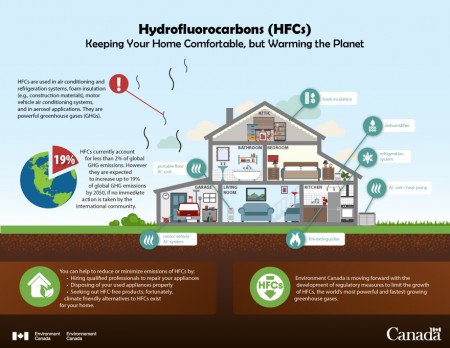

Hydrofluorocarbons

Known as HFCs, these are human-created fluorinated gases that we currently use in air conditioners, refrigerators, insulation materials, solvents, aerosols and fire retardants. Back in 1987, 24 major industrial nations agreed to limit a particular type of HFC called chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) because of their impact in creating holes in the stratospheric ozone layer. The control of CFCs and their disappearance was a major environmental achievement. But now with HFCs, our replacement for CFCs, we’ve created a new problem.

HFCs represent just 1% of all greenhouse gases we humans produce. They remain in the atmosphere for about 15 years. As small as their volume may be their global warming impact exceeds their footprint dramatically. Scientists forecast that by 2050 HFCs will be a one of the most significant contributors to anthropogenic climate change. Their contribution to warming is forecast by scientists as producing 0.1 Celsius (0.18 Fahrenheit) in overall global mean temperature rise by 2050.

The Three Amigos Agreement on Short-Lived Climate Pollutants

The leaders of Canada, Mexico and the United States when they met agreed to tackle all of the above short-lived climate pollutants.

For black carbon their commitment focused on an industry sector strategy building expertise and sharing information and technology focused on reduction and mitigation. In one specific area they focused on heavy-duty diesel vehicles with a goal to achieve near-zero emissions through adoption of ultra-low-sulphur diesel fuels and improvements in exhaust systems by 2018. The countries also agreed to establish a black carbon inventory with a goal to reduce industrial and domestic emission sources in all jurisdictions.

For CH4 the 40 to 45% reduction target by 2025 will be accomplished through sharing information on CH4 data including transparent reporting on emissions, cooperation on technology development, and an industry sector strategy which not only includes oil and gas but also agriculture and waste management. One goal is to meet the United Nations target of 50% reductions in global food waste by 2030.

For HFCs the three countries agreed to begin a phase-down in use with product-specific prohibitions and adoption of a comprehensive agreement similar to the one established for CFCs back in 1987.

For O3 the focus of all three countries is the promotion of clean and efficient transportation by accelerating government use of zero or near-zero emission vehicles, and by working with both industry (convening a meeting of all players no later than 2017) and consumers to see rapid adoption of clean-air technologies including deployment of an extensive clean refueling infrastructure across North America.

In addition the three countries agreed to begin to tackle maritime and aviation greenhouse gas emissions (particularly black carbon). Both of these sectors were left out of the COP21 Paris Agreement and their contributions to emissions will now be addressed at least by North America’s three nations.

For more details on what was agreed to refer to this weblink.